I have mentioned before that I want to return sometime to write a book that picks up again John A. T. Robinson’s case in his book The Priority of John that we can say things about the historical Jesus that some have insisted we cannot, and that the Gospel of John might prove surprisingly helpful in our attempt to do so. It occurred to me that my new book What Jesus Learned from Women connects with that quite directly. I have known for some time that the book is potentially revolutionary not only in what it explores and individual conclusions it draws but in its approach to doing history. I did not realize, however, just how directly this might connect with that broader interest. Robinson talks about the self-consciousness of Jesus as the “last tabu” in our quest for the historical Jesus. Even for those who take the humanness of Jesus fully seriously, who recognize that he learned and had human thought processes at work in his human mind, most historians have avoided the subject. Some of that is undoubtedly due to a reluctance to discuss matters that are inevitably going to be extremely controversial to conservative Christians, most of whom will insist that Jesus “knew everything.” To discuss how he drew conclusions, who taught him, or how he changed his mind is not just unacceptable but blasphemous to them. Although this is due to their being both unorthodox and unbiblical in their view of Jesus, historians still have enough controversy to not run headlong into others unnecessarily.

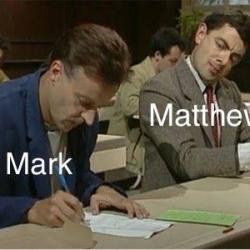

There is another reason why historians haven’t for the most part gone in this direction in their explorations, and that has served as a seemingly good excuse for avoiding the topic that isn’t just acquiescing to bullies. The Gospels do not organize material in chronological order. That makes the effort to trace development in Jesus’ thinking at best speculative and at worst impossible. Add to this the uncertainty about authenticity of individual sayings and about their original form even if they likely stem from Jesus, and a historian will feel they have good reason not to generate controversy trying to do something that quite possibly cannot be done. To trace development, as we can in the case of Paul the Apostle, we need to know what someone thought and in what order they thought it. We can compare Galatians and Romans and plot trajectories between the two. We can add in other letters and enrich our picture. The sources we have for Jesus’ teaching cannot be treated in the same way.

So how can What Jesus Learned from Women help? In a nutshell, the moments that are the focal point in the book’s chapters are moments when we see Jesus responding to people that he interacts with. In a number of chapters I suggest that, even if the order of some or even all of the Gospels may place other sayings or stories before a particular encounter, the logic of development may in fact suggest a different order in the actual historical unfolding of Jesus’ activity – and of his thinking. Even if I had thought to do so, I would not have tried to connect these points in the book to that future book I might possibly write or to the larger questions of historical methodology and what is possible when it comes to the historical Jesus. What I’m doing is controversial for plenty of reasons, in some specific cases where I propose a new interpretation of what is going on in a passage or champion one that is not widely accepted, but also just in terms of the overall point and theme. Jesus learning from women is enough of a focus for the one book! I do want to note, however, the potential I see in my historical investigations to make contributions to the quest for the historical Jesus as a whole. It goes far beyond what Jesus said and argued for as pertains to women, what it means for his teaching and his values. These stories in which Jesus learns things may provide anchors that represent watershed moments in relation to which we may be able to coordinate some of his sayings and teaching as earlier or later.

There are stories involving men and not just women that would be part of this approach, obviously. I mention the encounter between Jesus and a Roman centurion in my book, mostly just to discuss how it might relate to the story about the Canaanite or Syrophoenician woman. In the story Jesus is depicted as exclaiming “I tell you the truth, I have not found such faith in all of Israel!” Why do we not view this story as an “aha moment” for Jesus? Why do we not consider that the Gospel authors or their source may have included the story for that very reason, that it was recognized as a moment in Jesus’ life that had a profound influence on him? This approach, even if it doesn’t accomplish what I hope it might, could nonetheless be relevant to the question Philip Jenkins raised on his blog about Jesus’ view of Gentiles. If Jesus’ thinking changed and evolved as happens to all human beings, then we suddenly have an explanation available to us, one that is rarely if ever considered, for how it could be that both conservative and progressive trajectories could both claim to be faithful to Jesus on the question of Gentile inclusion in the people of God and the means by which they could be incorporated. One had the bulk of what Jesus said and how he referred to Gentiles in their favor. The other picked up on the direction his thinking was moving towards the end of his activity, and carried it even further in that direction than he did.

Line up enough watershed moments of this sort and they may provide the kinds of chronological anchors that, for the most part, the Gospels have been felt not to provide us with. This may give us a chance not to merely speculate that Jesus may have changed his mind, but to try to actually trace how his thinking developed. If doing this is difficult, trying to view Jesus as unlike every other human being in having static unchanging thoughts presents even greater difficulty.

I’m eager to find out what historians working on the historical Jesus make of this possibility. I hope that some who read the book will consider this and comment on it!