Some parts of the Bible raise a lot of questions and debates, and indeed are often cited as the detonators that drive people away from their faith. I offer an an unusual example, which offers quite a few challenges. Quite seriously, think of this as a Lenten exercise, comparable to the historical themes Chris Gehrz discussed here recently.

I had a friend (now deceased) who in his college years had lost his conservative Christian faith, and in fact became quite militantly anti-religious. He owed his deconversion to wrestling with a scriptural text. Such a story is of itself anything but unusual, except that the text involved was not one of the customary range of problematic readings in the Bible, such as the Genesis Creation story. It was Acts, chapter ten. In our discussions through the years, he raised questions that I find fascinating, and troubling. Let me explain, and in the process, raise an important issue for Christian apologetics.

For those among you who cannot instantly recall the tenth chapter of Acts (!), Peter is in Joppa where he receives a vision. (Joppa is adjacent to modern Tel Aviv). A sheet is let down from heaven, containing all sorts of creatures, and a voice commands Peter to kill and eat. Peter refuses on the ground that he strictly respects the food laws concerning what can and cannot be eaten. But a voice commands him that “What God hath cleansed, that call not thou common.” The vision recurs three times. This then sets the stage for Peter’s encounter with the Gentile centurion Cornelius and his household, who seek instruction. This is for Peter a very big deal indeed. As he explains, “Ye know how that it is an unlawful thing for a man that is a Jew to keep company, or come unto one of another nation; but God hath shewed me that I should not call any man common or unclean.” (10.28). Inspired by the vision, Peter preaches to them, whereupon they received the Spirit in what has been called the Gentile Pentecost. Peter then asks, “Can any man forbid water, that these should not be baptized, which have received the Holy Ghost as well as we?” So the Gentiles are baptized, and a new phase of the church initiated. I am summarizing a long, complex, and repetitive chapter. The date of the event is probably in the late 30s, or around 40 AD.

So why would this possibly undermine anyone’s faith? Here was my friend’s problem. The Gentile baptism here is clearly considered an amazing and shocking thing, which could only be validated by a specific divine command and a vision, “done thrice.” Even Peter, who could at times be, well, slow on the uptake, gets the message. So why did Peter not simply recall the Great Commission, which was presumably issued a decade or so before that? As we have the story, the risen Jesus appears to the disciples, including Peter, and tells them, “Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” (Matthew 28.19). The Greek is panta ta ethne, using the word for “nations” that pretty much everywhere else is translated as “Gentiles.” All nations. That would surely include, for instance, Gentile centurions in Caesarea.

My up till then rather fundamentalist friend was shocked. His sequence of thoughts went like this. Obviously, the Peter of Acts had never heard of such a Commission, which could not have been an authentically early text. It must have been added retroactively, after the church was very well accustomed to admitting Gentiles, and indeed, becoming mainly Gentile in composition. So right there, thought my friend, we have a gospel verse that was a retroactive addition to justify later church practice. The door was open to higher criticism, and to the question of just what else might fall into that category of retroactive editing and, he would say, invention.

In that view, Acts 10 is Luke’s version of the Great Commission, but it is conspicuously separate from any reference to Christ, even in a post-Resurrection context.

Compare the account of Jesus’s final post-Resurrection address to his disciples in Matthew and Luke. Matthew, of course, has the Great Commission. The parallel scene in Acts has Jesus send the disciples to be “my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1.7). Although we read this as a kind of Great Commission, it differs critically in the lack of any reference to “nations” or Gentiles. It is just a geographical command, which presumably referred to seeking out to Jews wherever in the Diaspora they might be found.

As my friend expanded his historical studies, and indeed became a formidable academic, he became intrigued and then alarmed. Apart from that Great Commission, he believed, the Jesus of the Gospels said nothing to substantiate or justify a mission to Gentiles. Nor did my friend see anything to support the view that Jesus’s exclusive focus on Jews (and probably Samaritans) was a temporary phenomenon, to be expanded at an opportune moment to a wider world.

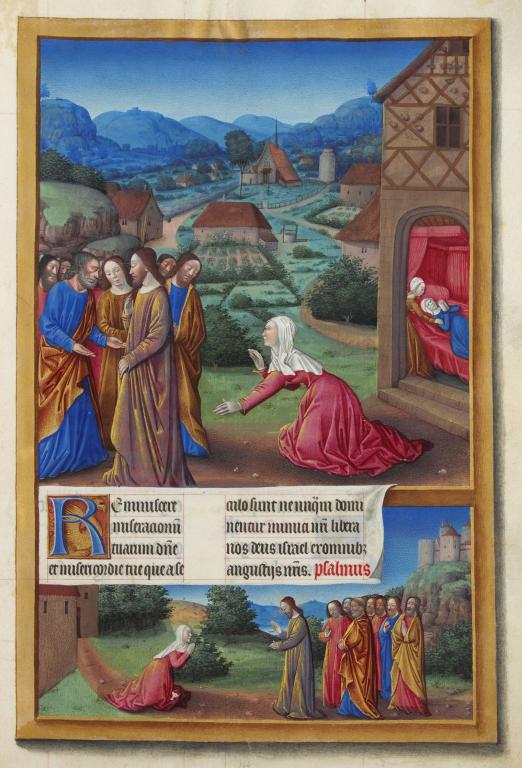

Jesus and the Canaanite Woman: Image is in public domain

Jesus, in fact, was quite explicit about this, in the harrowing story of the Canaanite woman of Mark 7, whom Matthew calls a Syro-Phoenician in his chapter 15. This Gentile seeks a miracle from Jesus, which he initially refuses because “Let the children be fed first, for it is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.” Matthew explains this remark to add that “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel,” and not to Gentile “dogs.” We note the word “only,” not “first.” Talk about “hard sayings.” (You can argue for a “first” in Mark’s version).

Then we note a really significant omission. This story is one of the passages in Mark that Luke did not choose to incorporate into his own gospel, and it is not hard to see why. That conscious and deliberate omission raises the question of what other Jesus stories or sayings were so hostile to Gentiles that they simply failed to be recorded in the scriptural record as we have it. Conversely, if Jesus actually had said many other things that were Gentile-friendly or Gentile-inclusive, it is hard to believe that the evangelists would not have leapt at the opportunity to incorporate them into the documents of a late first century world. Presumably, candidates for such appropriation were few or non-existent. Just as an exercise, look how the word for Gentile appears throughout the Gospels, and try to find some un-hostile-sounding examples. It’s not easy.

Beyond that Canaanite story, we really have little idea of what Jesus thought or said about Gentiles or “the nations,” but nothing suggested that they were to be brought into the new movement he was forming. This was certainly intended for all manner of outsiders, but specifically those lost and fallen sheep of the House of Israel. We can argue about where the Samaritans were meant to fit into that larger scheme.

That situation changed as the early missions expanded, and actually did bring in Gentiles. At some point during the first century, a story arose that Jesus had in fact foreseen and commanded this outcome, and had spoken on the subject – not admittedly during his earthly ministry, but during a Resurrection appearance. The story was however only picked up by Matthew’s gospel. If the saying was an invention of Matthew himself, then it is from the last decade or two of the first century. A parallel quote appears in Mark 16, but that latter section is almost universally taken to be a much later addition to Mark’s original (c.125?), and as it stands, it borrows wholly from Matthew.

So my friend’s conclusion was this. Jesus was a Jewish reformer or preacher, whose only concerns were with the people of Israel, and their redemption. His movement was never intended to be in any sense universal, except in the sense that a redeemed Israel would somewhere in the apocalyptic future attract the homage of Gentile nations, as prophesied in Zechariah 14. The “Jesus Movement” was never intended to have any Gentile representation whatever. Any belief to the contrary was a massive historical and theological blunder. Most or all of the universalism that is so often attributed to Jesus in modern-day sermons is a thoroughly retroactive imposition on documented reality. The Christian Church, in this view, was an epic mistake.

Now, there is an alternative view, namely that all Christologies acknowledge that an incarnate Jesus was limited by his human status, and arguably that included his strong and even exclusive commitment to Jewish values and approaches as they were constructed in that era. After the Resurrection, the church naturally blossomed out into its proper and destined universal form. That church, following the Spirit of Christ that inhabited it, made its “outreach” decision under that guidance, and in that sense, Jesus really did issue the Great Commission. But that is only one approach.

As I say, I am presenting my friend’s view crudely and rapidly, but that is a fair summary of it. Can we agree that it asks some very good questions? But even if we reject the larger historical framework offered, what are we to do with that very specific Joppa episode, if in fact the Great Commission story was an authentic recollection of Jesus’s words?

I’d love to hear some opinions on this. If I was still arguing with my friend, whom I miss, how could I try to answer him?