Lent is the season of the Christian year when many followers of Jesus — including a growing number of evangelicals — engage in spiritual disciplines that help them contemplate sin and mortality. We fast for Lent, pray for Lent, and often add a Wednesday night worship service for Lent. But I wonder if we might also want to study history for Lent.

Of course, study by itself is already a spiritual discipline. Whether its object is the written word of Scripture or anything that came into being through the living Word, study can become what Richard Foster calls a “means of God’s grace for the changing of our inner spirit,” as we come

to understand not only our subject matter, but ourselves. Jesus speaks often of ears that do not hear and eyes that do not see. When we ponder the meaning of what we study, we come to hear and see in a new way.

That’s often how I feel when I study the past, which is strange enough to discomfit my overly comfortable life and familiar enough to hold up a mirror to my shortcomings.

But this Lent, I’ve also started to think of history as a kind of fast. I don’t give up meat, caffeine, or Facebook, but I try to suspend my often anxious obsession with what’s to come. For time dedicated to understanding the past is time I don’t spend fretting about the future. In the process, I tend to recognize that what’s to come is no more within my control than what’s already happened, which may prepare me to live more prudently in the present.

Finally, there’s a way that the discipline of history can start to become a discipline of prayer. It’s not just that we can pray for understanding before reading or research, teaching or learning, but the experience of immersing myself in the past sometimes drives me to talk to God. He’s not much more likely to answer than the people I’m studying, but unlike them, God is listening to me. He hears the words that history brings to my mind: words of curiosity and confusion, excitement and exasperation, lament and rage.

And sometimes, when I descend to the darkest depths of the human past, I offer up my version of the most desolate prayer in Scripture: God, why have you forsaken us? (Ps 22:1; Matt 27:46; Mark 15:34)

I often tell students that the most important thing that can happen in any of my classes — more important than any of the learning objectives on page 1 of my syllabus — is that they might encounter God. I believe that’s possible, but I have to admit: it will seem far more likely that studying the kind of history I teach will make them aware of the absence of God, not his presence.

Maybe this isn’t true of all histories. But because so much of what I teach is the 20th century, the age of total war and genocide, class with me can feel like a semester-long dark night of the soul, with God-shaped holes around every turn: injustice without reform, suffering without relief, and death. So much death.

Take, for example, the sophomore-level general education course I’m teaching this spring on the international history of World War II. We’d only got as far as the 1937 Rape of Nanjing — during which Japanese soldiers raped, tortured, and killed hundreds of thousands of Chinese civilians and prisoners of war — before I got an email from a student: she’d decided to drop the course. She wanted to believe that something redemptive might be coming later in the semester, but between the atrocities I’d already recounted and the 50+ million deaths yet to come, the slender hope of distant light wasn’t enough to carry her through the thick darkness of WWII.

Part of me was just glad that she took that history — and her own emotional health — so seriously. Far easier for students to keep it at a distance.

But I did want to tell her that, once in a while, we will see light. When we think humanity can’t behave more abominably than it did during World War II, our story will come to a moment of unexpected courage or kindness — in Nanjing, a savior as unlikely as a Nazi businessman rescued thousands — and we see that the Image of God is badly obscured, but not eradicated.

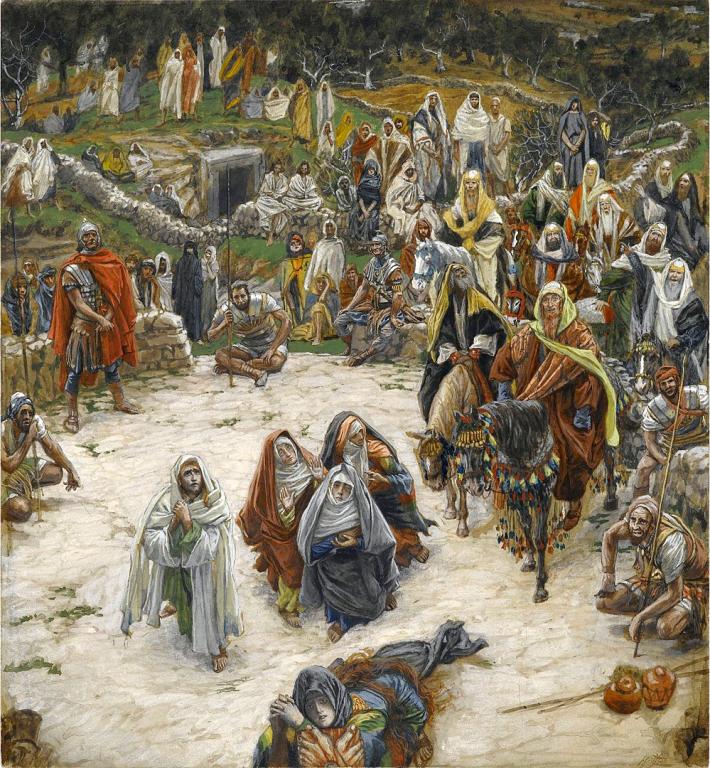

And just when we think that the Father is a forsaker after all, we see his Son among the people of the past — or, at least, we see the people of the past as Jesus would see them: through eyes brimming with compassion. As we realize how many women were sexually abused and exploited during WWII, we might see Jesus showing love to women deemed unclean by their society. As we encounter starvation as both a byproduct of the war and — in the case of Nazi Germany — an aim of it, we might glimpse Jesus, the Bread of Life, feeding multitudes. And as we imagine ourselves walking past columns of refugees and through camps of displaced persons, we might see the world as a very young Jesus saw it, when he fled his country for the safety of another.

The disciplined study of the past, then, is a way of contemplating sin and its cost: each moment in history one more fiber of wood composing the Cross. But like any Lenten discipline, such study is also a way of encountering the Christ who redeemed those sins, and seeing the world more as he saw it.

If you’d like to fuse historical study with devotional practice, visit the Conference on Faith and History website every Monday and Wednesday through Lent, then every day in Holy Week. There you’ll find a series of reflections that extend the work of Faith and History, the CFH devotional that Beth and I edited last year. Last week, for example, former Anxious Bench guest-blogger Regina Wenger, a graduate student at Baylor University, reflected on God’s covenant with Abraham in light of Anabaptist history in Africa. Tomorrow we’ll hear from Covenant College professor Jay Green, one of Beth’s predecessors as CFH president, as he considers more closely the relationship between history and death.