Present: Parallel Universes, Loving the Alien in Our Midst, and Robots in Church

We have already been in the present in our discussion, and indeed we never really leave it. Science fiction may be usefully compared to prophecy, but prophecy isn’t really about prediction with accuracy. The point of invoking a vision of the future or of time travel to the past is to offer a message for our present day. Even when Octavia Butler offers a glimpse of the future that is so on-target that is envisages a presidential candidate who promises (and I quote) to “Make America Great Again,” the point is not to see how many details are precisely correct and how many look as off-target as the now-unimpressive communicators in the original series of Star Trek. It is a vision of where things might go that calls us to self-examination on the individual and societal level, and to repentance.

One way it does so is to explore alternative presents. The story in Devs discusses the possibility of many parallel universes, constantly branching off from one another, each slightly different, but some exponentially so. Even without invoking other universes, Star Trek and other franchises have explored planets on which life arose and history followed a course much like that of Earth, but with some differences. The original series episode “Bread & Circuses” frames its visit to one such planet in religious terms from start to finish. That world is one in which the Roman Empire never fell, so that there are still gladiatorial games, but they are broadcast on television. When the members of the Enterprise crew beam down to the planet, they have a discussion that alludes to the Bible, with McCoy saying he wishes that just once he could beam down to a planet and say “Behold, I am the archangel Gabriel.”

Here we get the idea of Clarke’s Law, that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic, or miracle, or the supernatural of whatever sort. This in combination with the story of Apollo raises the possibility of Daniel, Mary, and others seeing someone from a more advanced civilization and categorizing them as an “angel.” That is indeed the scenario featured in Erich von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods and other books. Ancient Aliens is obviously terrible history. Yet it is popular in science fiction. Why should that be? And why is affirmation of the literal truth of ancient myths and religious tales, but with supernatural entities reclassified as aliens, felt to be preferable to some, and an attack on one’s faith by others? This is just one way people have tried to preserve and yet simultaneously adapt ancient myth and religion to a scientific framework. Is it ironic or entirely expected that the result seems to most to be unscientific, poor history, and religiously unsatisfying?

Returning to the Star Trek episode, near the end, as those who were in the landing party are discussing their experience, still puzzled by the significant difference from Earth history that on this planet a major movement were worshippers of the sun, Uhura chimes in to explain to her colleagues what they’ve misunderstood. They don’t worship the sun in the sky, but the Son of God. Kirk then realizes that they had both Caesar and Christ after all, and suggests it would be something to watch it happen all over again.

Gene Roddenberry was famous for his humanism, and while he has often been assumed to be an atheist hostile to religion, that characterization doesn’t fit either what he said in interviews or what we see in the show. There is criticism of organized religion, to be sure, but also appreciation for an influence without which the reign of vicious and tyrannical power might never have been tempered with a vision of equality and love.

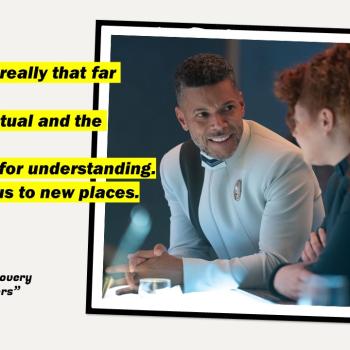

The question of what history might have been like if there had been no Jesus and no Christianity is sometimes pondered but rarely if ever explored in detail. We can, however, ask whether one well-known parallel universe might not be relevant to this topic, even if no story within the franchise explicitly suggests it has anything to do with our topic. Star Trek introduced a “mirror universe” in the original series episode “Mirror Mirror” (which in the talk, presumably due to my love of progressive rock in addition to sci-fi, I referred to as “Spock’s Beard”!) that has been revisited many times since, right down to the current iteration, Star Trek: Discovery. That universe features an Empire rather than a United Federation of Planets, and it is characterized by ruthless ambition and violence. How did they end up so different? We aren’t told. What if we imagine this as a possible world without Christianity, and of course also without other religious and ethical traditions that served to temper human greed and selfishness? Would it fit, and if so, what interesting reflections could it lead to? We don’t have time to explore this here. I will merely say that contemplating this possibility should not be an occasion for smug superiority. Christianity has regularly been involved in the imperial enterprise (pun intended). If we use the mirror universe to help us imagine a world without Christianity, we should also proceed to imagine a parallel universe in which Christians were truer to the example and teaching of Jesus. A science fiction mirror universe can help us see ourselves and our religions more clearly.

There is literature relevant to this, including John Boyd’s Last Starship from Earth. I also want to mention Chris Crawford’s novel The Tuning Station which allows two versions of the same individual in parallel universes, one a Christian and the other an atheist, to meet in a place that allows them to try to pinpoint the moment when their paths diverged along different trajectories.

There are plenty of other ways that science fiction allows us to think about the present in different ways. Countless stories–from War of the Worlds (in multiple variations) to Carl Sagan’s Contact to numerous episodes of Black Mirror—present religious people reacting in unhelpful and at times downright appalling ways to new situations. Such works are probably the reason why some view science fiction as taking a negative stance towards religion in general or Christianity in particular, with some Christian leaders and churches reciprocating. These are at best caricatures, just as the depictions of religious people in science fiction have sometimes been caricatures or at least rather flat stereotypical characters. Caricatures nonetheless tell us something about how groups are perceived by others. Sometimes they reflect simple antipathy. At others they represent something that is genuinely there exaggerated into a distorted image intended to mock and ridicule. Sometimes what a few individuals or groups have done is treated as though it were a universal trait of a community or species, becoming prejudice. Science fiction has often generalized, giving the impression initially that there is only one way (or at least only one correct way) of being Vulcan even though there are so many different ways of being human. Some may insist that there is only one way—the way of the Mandalore—but others who are heirs to the same tradition may disagree.

When the alien is depicted in these ways, it is regularly offered as a critique of real-world phenomena and tendencies. Those who read Bible translations that literally speak of welcoming the alien in your midst may be particularly struck by the irony of how often anti-alien sentiments are associated with Christianity in science fiction. Those who have seen real-world examples of failure to be hospitable to strangers may find it more poignant than ironic. Thinking about extraterrestrials and robots helps us to see our tendency to dehumanize and to deny human rights to others. In a world with aliens and/or A.I.s it becomes clear that even merely respecting all humans doesn’t go far enough. Science fiction probes at the limits of our inclusivity, and whether we can get beyond merely tolerating difference to an appreciation of “infinite diversity in infinite combinations.”

Science fiction does not have to be depicting Christianity in order to have something important and interesting to say about it and to it. It should not take a depiction of Jesus coming on scene to say “Many will come from Arrakis and Coruscant, from Gallifrey and Vulcan, and will take their place alongside Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in the Kingdom of God” for us to understand the relevance of what sci-fi does to what Christianity has at times led the charge in doing, and at other times has utterly failed to do.

Stay tuned for the next part!