A while back Eboo Patel encouraged students to pursue degrees in the liberal arts for a reason that I had not heard used before: because of robots. His argument is that robots will replace most manufacturing and other skill-based jobs, and it will be those who have mastered the creativity and other thinking skills that humans can offer, but machines cannot, who are most likely to retain their usefulness in the technological future.

This may or may not be good advice, in the short term. But does the assumption that liberal arts capabilities will remain exclusively in the hands of biological humans represent a reasonable and reliable inference, or merely a lack of imagination with respect to the future of technology? When it comes to artificial intelligence (AI), much of what we can say at present is going to be at best hypothetical, and at worst highly speculative. But maybe that’s OK: how we speculate about and imagine the future is itself worthy of study, since doing so makes us aware of, and provides opportunity to reflect on, our own present-day assumptions and values.

For instance, it is often assumed that artificially-intelligent machines will be rigidly logical. This may be true – especially if we do not create for our AIs something equivalent to the hormonal systems and other body chemistry that our human emotions are rooted in. What is especially interesting is the way that different authors assume that such rigid rationality and logic will lead AIs inexorably to the conclusion that God exists – or that God does not exist. Fewer envisage, much less explore and reflect on, alternative possibilities, in which machine intelligences, like their human creators, cannot simply reason to a clear and definitive answer about such matters. One of those exceptions is the British television show Humans, which is based on a Swedish show called Äkta människor (“Real Humans”). In an episode in the first season, when a sentient synthetic human gets separated from those he considers his family, he eventually drops to his knees and, after briefly acknowledging the statistical improbability of God’s existence, nevertheless proceeds to offer a prayer that they might be reunited – a prayer which engaged in some characteristically human bargaining with the divine.

That fictional scenario highlights the massive gulf that still exists between our rudimentary attempts at producing artificial intelligence thus far, and one that would incorporate human characteristics such as sentience. Today we can talk not just using our phones, but to our phones. But the phone cannot at present “understand” what you say, in the sense of being able to consider it and then offer its own spontaneous response. Siri can respond to verbal inputs in ways that it has been programmed to. Her inability to provide assistance when you ask her to pray for you is entirely a result of her programming (Randall Reed recently shared a similar experience of asking Google Home and Alexa about their religious stances). Yet even if a different programmer had prepared Siri to utter an Our Father or Hail Mary when so prompted, many would say that the digital production of the sounds corresponding to those prayers would be religiously worthless, since they did not emerge from a genuine personal devotion. Then again, there are humans who would criticize the prayers of other human beings along similar lines. The question remains open whether we can ever produce a machine intelligence that can choose whether to be religious or not. But once again, some human beings view the religiosity of their fellow human beings as merely a result of their “programming” – otherwise known as their upbringing. What is it, then, that would differentiate a sentient artificial intelligence from what we can currently produce? Perhaps the ability or inability of the AI to empathize with the human who asked it for prayer. Rather than churn out a rote set if words, or refuse to do so because it has been programmed accordingly, a truly sentient AI might not only recognize in the request for prayer an indication of personal need or distress, but actually care about what the person is going through. Here too, however, we find that human beings sometimes fail to empathize with one another, and the question of how to teach caring proves incredibly challenging, even when both teacher and student are biological human beings. There is thus some hope that our attempts to produce and teach artificial intelligences may also offer clarity to a variety of aspects of human existence.

Also related to the intersection of science, technology, sci-fi, ethics, and/or religion in various ways, and so of likely interest to anyone reading this:

To See A World In A Grain Of Silicon: Why Minds Aren’t Programs

Brain-Computer Interfaces: Extended Agent or Disappearing Agent?

Amid a Pandemic, a Health Care Algorithm Shows Promise and Peril

The cost to own your own robot dog

NASA is heading to Venus to understand Earth and exoplanets better

Despite the pandemic we broke a carbon dioxide record

ProctorU abandons AI-only approach to detecting cheating. Humans need to check their work.

Virtual office hours should continue post-pandemic (but we should stop calling them that)

New tech crossing traditional silo boundaries

Insurers ask who pays when self-driving vehicles crash

Tesla cars will spy on you to avoid future PR disasters

Self-sustaining electronic microsystem

We have entered the era of killer drones

The AI behind Facebook’s TextStyleBrush is sure to prove useful to scholars…in the long run

Left, Right, and Criticism of Big Tech

Lawmakers want to break up Big Tech

The movement to protect your mind from brain-computer interfaces

Short film seeks to depict a realistic lunar colony

How would Jesus Christ have used the Internet?

https://www.thetechedvocate.org/the-amazing-power-of-ed-tech-on-connecting-classrooms/

https://www.thetechedvocate.org/a-framework-for-for-successful-implementation-of-technology/

From First Monday: “The Coming Age of Adversarial Bot Detection” and “Four Years of Fake News”

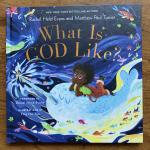

The Best Friends are Artificial – Kazuo Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun