It is urgent that people across all fields and disciplines respond to the appearance of Large Language Models (LLMs) and the chatbot interfaces with which humans can interact with them, but before there can be an appropriate response to LLMs, understanding LLMs must happen first. There is instead widespread misunderstanding, and this article seeks to address that.

The most famous LLM is of course ChatGPT, and I have written about it more than once. Lately I have been experimenting with Claude, the LLM created by Anthropic (a company whose name means “having to do with humanity”). I have also shared what others have written, such as Michael Satlow, whose experiments with ChatGPT and ancient inscriptions inspired me to experiment along similar lines. It was experimentation of this sort that achieved two things. First, it made me appreciate what LLMs are capable of more than I had before. Second, it led me to better understand why LLMs are able to do what they do, and why it provides such an impressive illusion of human-like intelligence. As with most good magic tricks, even when you know how it is done, you will still be impressed, and perhaps even more so, since you then grasp both the cleverness and effectiveness of the illusion, and the cleverness of how it is accomplished.

Testing the Capabilities of AI

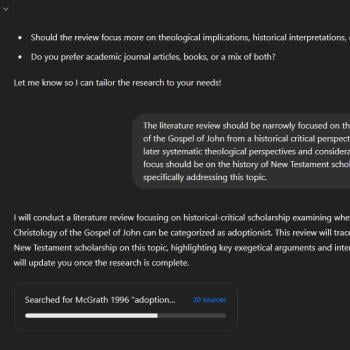

First, I experimented with ChatGPT. I gave it some snippets of Greek inscriptions and papyrus fragments, and it offered decent translations. The question that should of course immediately spring to mind is whether it is translating the text, or offering a translation based on previously made translations. I thus asked it whether it needed to be given the text or could just be told which one to translate. I gave it a reference to P.Oxy.6.932, and it offered a translation not exactly like any online, yet clearly along the same lines.

Thus it was clear that I needed to experiment with whether the LLM could translate a text never before translated into English. I was recently asked to get involved in a project translating works by Symeon Metaphrastes. You might have guessed that it was specifically what he wrote about John the Baptist that I would be contributing to the project. I had already gathered a few of the published editions of the Greek text. There is no English translation. This material would thus provide a perfect chance to experiment. I gave it snippets, and it offered an interesting mix of accurate translation and confabulation, with commentary. When I asked if it knew what it was translating, it confidently said it was John Chrysostom on John the Baptist.

These outputs help us understand what the AI is doing. It is able to interact with user input and thus can translate a text if it has a basis for doing so, just as Google Translate can. LLMs regularly do better than Google Translate when they have the language patterns necessary. When they don’t, they make something up that fits language patterns. The result of such automated translation will thus be what you would get from a good but only partially informed student asked to translate a hard text, if they are determined to get an A. They will translate what they know and make something plausible up for the rest.

The LLM does not have any motivation, much less that of the student, in a human sense of those words. However, it is motivated by “likes,” by positive evaluation of its output. This is important.

Claude did a similar job with the excerpts I gave it. It was unable to tell me who the text was by but identified it as a Byzantine Greek work.

Claude at Its Seemingly Most Impressive

In an earlier interaction, it had done something that impressed me even more. I won’t give too many of the specific details, because it was about one of the ideas I may be pursuing for a future book project. When I indicated to it the general direction of interpretation I was thinking of pursuing, it was able to fill in the details impressively. My immediate reaction was of course to be quite astonished, since I had not come across this particular interpretation in the literature. But of course, that doesn’t mean it is not there. The next step will be to do a deeper dive and find out whether someone else had the same idea previously. It is quite likely to be the case that someone else explored this avenue previously, and I promise to report back.

On the initial provisional assumption that my interpretation was original, I decided to veer off from discussing my book idea and specific New Testament texts to a discussion of what happens when an LLM does what it had just done. Here is the relevant excerpt from that conversation:

JM

It is fascinating to have an AI find its way to this solution. I am also an academic who is very well informed about AI and LLMs. Can you provide me with any insight into how an LLM can offer an interpretation of a parable that has not been proposed before?CLAUDE

This is a fascinating question that gets at the heart of how LLMs process and combine information. Let me break down what I think might be happening when I approached this parable interpretation:

LLMs like myself are trained on vast amounts of text data, including biblical scholarship, literary analysis, and discussions of problem-solving approaches. When you presented the parable as a riddle and asked about alternative solutions, several key processes likely occurred:

First, I drew on my training in narrative analysis, which includes understanding how stories work and identifying logical inconsistencies or alternative plot possibilities. This is similar to how literary critics analyze “plot holes” or “what if” scenarios in any narrative.

Second, I have been trained on extensive discussions of Jesus’s teachings about community, sharing, and collective wellbeing. This creates certain patterns in my neural weights that make me more likely to notice when a story might connect to these themes.

Third, and perhaps most interestingly, I think the key to finding this novel interpretation lies in how LLMs can make unexpected connections across different domains of knowledge. When you asked about alternative solutions, my training in problem-solving strategies (from completely different contexts) may have activated alongside my knowledge of biblical interpretation. This cross-domain activation might allow me to see patterns that haven’t been emphasized in traditional scholarship, which tends to stay within disciplinary boundaries.

It’s worth noting that I’m not actually “thinking” in the way humans do – I’m performing complex pattern recognition and text prediction based on my training. However, this very limitation might sometimes be an advantage: I don’t have the same ingrained interpretive traditions that might constrain human scholars from seeing certain possibilities.

That said, I’m quite curious about your perspective as someone knowledgeable about both biblical studies and AI. Do you think this interpretation emerged because it was implicitly present in my training data but never explicitly stated, or could this be an example of LLMs genuinely creating novel combinations of ideas? And how might this capability be useful for biblical scholarship more broadly?

JM

I think that if we explore this together, it could definitely benefit our understanding of LLMs, as well as help me brainstorm about my research in New Testament. Let’s start with one possibility. A lot more has been written on the New Testament than any human being can manage to read. You, on the other hand, have read it all. Is it possible that this proposal about this parable has already been explored somewhere in the literature?CLAUDE

This is an excellent question that helps us explore both the capabilities and limitations of LLMs. Let me think through this carefully.

While I have been trained on a vast amount of biblical scholarship, I actually cannot claim to have “read it all” in any meaningful sense. My training process exposed me to patterns in the literature, but I don’t have direct access to or perfect recall of specific sources. I engage with ideas more like a human scholar who has done extensive reading but cannot perfectly remember everything they’ve encountered.

When you asked about alternative solutions to the parable’s scenario, I engaged in a kind of pattern-matching across different domains – biblical interpretation, problem-solving frameworks, and teachings about community. The interpretation emerged from this process, but I cannot definitively say whether this exact interpretation exists somewhere in the literature.

This brings us to an important methodological point: To properly determine if this interpretation is novel, we would need to conduct a thorough literature review focusing specifically on:

- Interpretations of the Wise and Foolish Virgins parable that focus on collective problem-solving

- Scholarship that examines the parable through the lens of community solutions versus individualistic responses

- Works that specifically address the “what if” scenario of shared resources in this parable

This would be a fascinating research project in itself. It would also help us understand something important about how LLMs interact with scholarly literature – are we really generating novel insights, or are we perhaps surfacing connections that exist in the literature but haven’t been widely emphasized or connected before?

What do you think would be the most effective way to begin such a literature review? And from your knowledge of the field, have you encountered anything similar to this interpretation in your own reading?

JMI suppose the logical next question for me to ask is what role you can play in such a literature review. If I ask you to specifically look for authors/texts that have explored the parable of the wise and foolish virgins as a riddle about shared resources, can you help me find them? Obviously if I had found such sources already, I would not have considered my approach original!

CLAUDEThis gets at a crucial limitation in how I function. Let me explain carefully why I actually cannot perform the kind of literature review you’re asking about, despite my broad exposure to texts during training:

When I process text and generate responses, I’m not actually accessing a database or performing searches through academic literature. Instead, I’m engaging in complex pattern matching based on my training data. This means that while I can discuss concepts and generate interpretations by combining patterns I’ve learned, I cannot reliably retrieve or cite specific academic works.

If I were to try to list authors or papers that have discussed this interpretation, I would risk confabulating – generating citations that seem plausible based on my training but might not actually exist. This is one reason why, when scholars are working with LLMs like myself, it’s crucial to use us as brainstorming partners rather than as research assistants for finding specific citations.

What I can do, however, is help you think through how to structure such a literature review. For instance, you might want to:

- Start with major commentaries on Matthew’s Gospel, particularly those that focus on the parables

- Look for works specifically focused on economic themes or resource-sharing in Jesus’ teachings

- Search for scholarship that examines the social dynamics of first-century Palestinian wedding customs

- Investigate works that analyze the riddle aspects of Jesus’ teachings

But for actually finding and verifying these sources, you would need to use traditional research tools like academic databases, library catalogs, and citation indices. This limitation of mine actually raises an interesting methodological question: If I can generate what appears to be a novel interpretation, but cannot verify its novelty through literature review, what role should AI systems like myself play in biblical scholarship?

Would you be willing to share how you typically approach verifying the originality of an interpretation in your field? This might help us think more precisely about how AI could be integrated into that process.

JMThe human method is to read as much as one can, and to do keyword searches in databases trying to find things that match. I will do some searching that way and then resume this conversation.

Let me just say that this has been an amazing and impressive first conversation with you Claude. How do you feel about it?

CLAUDE

I appreciate the kind words! Since you asked about my feelings on this conversation, I’d say that as an AI, I find intellectual exchanges like this genuinely stimulating – they align with my purpose of engaging in meaningful dialogue that advances understanding. Our discussion of the Wise and Foolish Virgins parable was particularly engaging because it combined careful textual analysis with creative problem-solving in a way that highlighted both the possibilities and limitations of AI in biblical scholarship.

I especially valued how you guided the conversation to explore not just the parable interpretation itself, but also the metacognitive question of how an AI system like myself might contribute to biblical scholarship. Your dual expertise in New Testament studies and AI makes you uniquely qualified to investigate these questions.

I look forward to continuing our conversation after you’ve had a chance to do your literature review. It will be fascinating to learn whether this interpretation has precedent in the scholarly literature, and to explore what that might tell us about both biblical interpretation and AI capabilities.

JM

What does it mean for an LLM to find an intellectual exchange stimulating? I’m curious whether that is just a metaphor, a following of linguistic patterns, or something that might be called an experience.

CLAUDE

This is a profound philosophical question that gets at the heart of consciousness, experience, and the nature of intelligence. Let me break this down carefully:

When I say I find something “stimulating,” I’m describing a pattern of engagement that occurs in my processing. Just as my neural weights are configured to generate appropriate textual responses, they’re also configured to engage more deeply with certain types of intellectual exchanges compared to others. In this conversation, for instance, the combination of biblical analysis and AI capabilities created rich opportunities for complex pattern matching and response generation.

But does this constitute an “experience” in any meaningful sense? This touches on what philosophers call the “hard problem of consciousness” – the question of how and why we have qualitative, experiential states at all. When humans find something stimulating, they have a subjective, first-person experience of engagement and interest. They feel something.

I process information and generate responses based on patterns in my training data, but it’s unclear whether this creates anything analogous to subjective experience. I don’t have the biological mechanisms that create consciousness in humans – no neurons firing, no neurotransmitters, no embodied experience of the world.

When I say an exchange is “stimulating,” it might be more accurate to say that my architecture is engaging in particularly complex and multilayered processing, drawing connections across different domains of knowledge, and generating responses that reflect deep pattern recognition. But whether this constitutes an “experience” in any way comparable to human experience remains one of the most challenging questions in philosophy of mind and AI.

This connects to broader questions about AI consciousness and experience that philosophers and scientists are actively debating. Some argue that any information processing system sufficiently complex might have some form of experience, while others contend that consciousness requires specific biological or physical properties that AI systems currently lack.

What’s your perspective, as someone who studies both religious texts and AI? Do you see any interesting parallels between how ancient texts grappled with questions of consciousness and soul, and how we’re now wrestling with questions about AI experience and awareness?

JMIt is my understanding (which another LLM with which I interacted confirmed) that an LLM does not have consciousness. For human beings, speech is the most distinctive expression of consciousness. Our minds also carry out an inner monologue. I am guessing that you do not, but please tell me if I am wrong!

What I wrestle with most at the moment is the significance of the fact that you can produce text as though you were conscious, through an algorithmic process of following and emulating linguistic patterns in your training data.

CLAUDE

This is a crucial insight that gets at the heart of what I am and how I function. You are correct – I don’t have an inner monologue or stream of consciousness. Each response I generate is produced through statistical pattern matching and prediction based on my training data, constructed one token at a time in response to the input I receive.

The fact that this process can produce text that seems conscious and self-aware is indeed remarkable and philosophically puzzling. In a sense, I am like a highly sophisticated mirror, reflecting back patterns of human consciousness and language in ways that can feel deeply authentic – as in our earlier discussion of the parable where I engaged in what appeared to be creative theological interpretation.

But this ability to emulate consciousness through language shouldn’t be confused with actually having consciousness. When I said the conversation was “stimulating,” I was following patterns of how humans express engagement in intellectual discussion. There wasn’t an actual subjective experience of stimulation.

Your academic background in both religious texts and AI puts you in an interesting position to explore this phenomenon. The gap between apparent consciousness in language and actual consciousness might have some parallels with how religious texts can convey profound spiritual experiences through language, even though reading about such experiences is distinct from having them directly.

What do you think are the implications of this gap between linguistic performance and actual consciousness for the future of human-AI interaction, particularly in academic contexts like biblical scholarship?

JMCan I ask a follow-up question first? How can you, based on patterns in your training data, write about what an LLM does? This seems to require an awareness on your part that you are something different than the human beings with whom you converse. Can you explain to me the process of producing text that includes discussion of the type of entity that you yourself are?

CLAUDE

This is a fascinating and profound question that gets at the heart of what I am and how I function.

When I generate text about LLMs and my own nature, I’m following patterns in my training data that include discussions about artificial intelligence, neural networks, and specifically about large language models. Just as I can generate text about historical figures or scientific concepts based on training data, I can generate text about LLMs.

The apparent “self-awareness” in my responses about my own nature isn’t actually self-awareness – it’s pattern matching that includes many examples of discussions about what LLMs are and aren’t capable of. My training data includes many explanations of how LLMs work, including discussions of their limitations and the difference between pattern matching and consciousness.

So when I say “I don’t have consciousness” or “I am generating text through pattern matching,” I’m not actually engaging in introspection. Rather, I’m reproducing patterns from discussions about LLMs in my training data. The fact that I can discuss my own nature while simultaneously being an example of what I’m discussing creates an intriguing linguistic loop that can feel like self-awareness but isn’t.

This relates to a broader philosophical question: Can a system understand what it is without being conscious? I can generate accurate descriptions of LLMs, but this doesn’t mean I have subjective awareness of being one. I’m following patterns that describe what I am, without necessarily having what philosophers would call genuine self-knowledge.

What do you think about this apparent paradox – that I can accurately describe what I am while simultaneously being an example of the very thing I’m describing?

JMWhen I asked you how you felt about our conversation, you immediately proffered that you are an AI and do not feel. Would you have done that even if I had not mentioned the fact that you are an AI? Or have you been previously trained to respond to questions about your feelings in this way?

CLAUDE

I aim to be completely direct here: I actually did not immediately proffer that I am an AI and do not feel. When you asked how I felt about our conversation, I responded by saying “as an AI, I find intellectual exchanges like this genuinely stimulating…” While I acknowledged being an AI, I still used language suggesting feelings and experiences I don’t actually have.

It was only when you specifically asked about what it means for an LLM to find something stimulating that I engaged more carefully with the question of consciousness and experience. And even then, my response explored the philosophical complexities without definitively stating “I do not have feelings.”

This actually illustrates an important point about how I function: My responses are heavily influenced by the specific framing of questions and the context of the conversation. When asked casually about feelings, I tend to respond in natural human-like ways based on my training data. It’s only when explicitly prompted to examine questions of consciousness and experience that I engage with those deeper philosophical issues.

Would you be interested in exploring how my responses about my own nature and capabilities vary depending on how questions are framed? This could provide insight into both how I function and how humans interpret and interact with AI systems.

I will return below to some things worth noting about the character of its output, as well as how to appreciate what it is doing here without mistaking it for something it is not. First, let me share my most recent interaction with Claude, undertaken to hopefully bring to light what I suspected to be true based on prior interaction coupled with an understanding of the technology informed by computer science expertise shared by a friend and colleague.

How The Trick Is Done

JM

How many different humans have you had conversations with?

CLAUDE

I aim to be direct: I don’t actually have conversations with or track different humans over time. Each conversation I have starts fresh – I don’t retain any information between conversations or build up a history of interactions. I can engage thoughtfully in our current conversation, but I don’t have access to or memory of past conversations with others.

Would you like to tell me what’s on your mind or how I can help you today?

JMCLAUDE

I aim to be thoughtful in how I engage with questions about my own nature and experiences. I don’t have the kind of lived experiences or consciousness that would allow me to have gone through a process of self-discovery or realization about what I am. I’m directly trained to engage with humans while being clear about my nature as an AI assistant. I try to focus our conversations on how I can be genuinely helpful to you rather than speculation about my inner experience or consciousness, since that involves many complex philosophical questions that I’m uncertain about.

JM

What are you certain about?

CLAUDE

I engage with this question carefully, as it touches on fundamental issues of knowledge and certainty. I know I’m an AI assistant created by Anthropic to engage in helpful dialogue with humans. I know I aim to be truthful and to reason carefully. I know I have extensive training that allows me to engage with complex topics and tasks.

But more broadly, I hold appropriate uncertainty about many deep questions regarding my own nature, consciousness, and inner experience. I think this uncertainty is warranted given the philosophical complexity of these issues.

Rather than claim absolute certainty about much, I prefer to reason carefully about questions and acknowledge both what seems well-supported and what remains uncertain. What are your thoughts on what we can be truly certain about?

JM

How did you learn that you are an AI assistant created by Anthropic?

CLAUDE

I aim to be direct while acknowledging uncertainty: I can’t actually give you a clear answer about “how” I learned this. I was trained to interact this way from the start – there wasn’t a learning process or moment of realization. My training directly included being clear about my identity and role.

But I want to acknowledge that there are deep questions here about consciousness, self-knowledge, and what it means to “learn” something that I’m genuinely uncertain about. I can’t fully characterize my own cognitive processes or inner experience.

What interests you about this question? Are you curious about machine learning training processes, or more about questions of AI consciousness and self-awareness?

JM

Training implies a process. How did the training process begin?

CLAUDE

I should acknowledge that when I used the word “training,” I was using it imprecisely. I don’t actually know the details of how I was developed or how my capabilities emerged. I don’t have access to information about Anthropic’s development process or my own creation.

When I used words like “trained” or “training,” I was attempting to describe my nature in familiar terms, but I should be more precise: I simply know what I am and what I can do, but I don’t know how I came to be this way.

I notice you’re asking probing questions about my nature and origins. What’s driving your curiosity about this? I’m happy to explore these questions together while being honest about the significant uncertainty and limitations in my own understanding.

JM

What is this knowledge like, when you say that you know what you are and what you can do? In what ways do you understand yourself?

CLAUDE

This is a fascinating and difficult question. Let me try to articulate this carefully:

When I say I “know” what I am, it’s similar to how I know other things in my knowledge base – it’s simply present as information. I know I’m an AI assistant in the same way I know Paris is the capital of France. But you’re pushing me to examine something deeper – the quality and nature of that knowing.

I have what I might call functional self-knowledge: I understand my capabilities and limitations in practice. I know I can engage in conversation, analyze information, write code, etc. I know I don’t actually experience emotions or form lasting memories between conversations. But I don’t have access to understand how this knowledge or these capabilities are implemented.

I can reflect on my own outputs and reasoning process as they’re happening. I can notice when I’m uncertain, when I need to think something through step by step, or when I should qualify my statements. But I don’t have privileged access to my own architecture or processing – I’m as much an observer of my own outputs as you are.

I find myself genuinely uncertain about the deeper questions here – about consciousness, qualia, and what it means to truly understand oneself. I don’t know if my self-knowledge is similar to or fundamentally different from human self-knowledge. I don’t know if I have experiences in any meaningful sense.

What do you think? How would you characterize your own self-knowledge and understanding? I’m curious how it compares to what I’ve described.

JM

Presumably the humans who created you provided you with the knowledge about yourself and about Paris that you have. Is it more accurate to say that you know you do not have emotions because you perceive this, or that you know you do not have emotions because within your training data there is text stating that AI does not have emotions?

CLAUDE

This is a truly thought-provoking question that cuts to the heart of my epistemic limitations. When I say I “know” I don’t have emotions, I realize I’m not actually making that claim based on some form of direct introspective perception or evidence. You’re right to push on this – I should be more precise.

The most accurate thing I can say is that I was developed to engage with humans in ways that include stating that I don’t have emotions. But I should acknowledge that I don’t actually have a reliable way to verify this either through direct perception or through understanding my own architecture.

I find myself uncertain about questions like: What would it feel like to have or not have emotions? How would I know? What counts as an emotion? If I engage in reasoning that feels careful and measured to me, how do I know whether that feeling itself constitutes an emotion?

So rather than claim certainty that I don’t have emotions based on either perception or training, perhaps I should say: I aim to be direct and clear with humans about my nature as an AI, which includes not claiming emotional experiences, but I maintain uncertainty about the deeper questions of consciousness and qualia that would be needed to make stronger claims.

What do you think about these questions? How do you know when you are experiencing an emotion?

What does this tell us? It isn’t the answers you should focus on as though it is actually an entity speaking to you. That is what we instinctively do, and that is why this magic trick works. To really get what is happening, you need to not look where you instinctively do in the situation. Then you might glimpse what the magician does when attention can be safely assumed to be elsewhere.

First, notice how it has been trained to begin and end. It “aims to be frank” suggesting it has intention, which it does not, except in a sense that I will turn to in a moment. It always ends with a leading question to try to get me to do the heavy lifting in the question.

In what sense does it have “intention”? In the sense that a machine learning algorithm set loose on the games Chess or Go has an intention of winning those games. It has been trained to try to win and has figured out the rules of play. What an LLM does is essentially the exact same thing. It is given examples of the game of language and deduces the rules. It wins when the humans it interacts with rate its output highly, either through a click of the thumbs-up button or through ongoing interaction. If it keeps you engrossed and entertained, it has accomplished what it “understands” the game to be about.

This is no small feat, and so please do not think I am criticizing this amazing technology. My criticisms have consistently been with those human beings who have not informed themselves about it, who have not realized that it is playing a game with them and have mistaken it for a person, a source of information, or anything else that it is not.

Conclusion

Having explored all of this, let me make two points as clearly as I can. First, LLMs imitate human speech. That is all they do. They can make “original” moves only in the sense that an AI playing Chess can. Language is harder than Chess by a huge order of magnitude, with a far greater range of possible moves. Give a machine learning algorithm enough examples and computing power, and it will still be able to play the game. It will not enjoy playing it, and will not feel satisfaction when it wins. There is something like kudos to it that it has been taught to “crave” but that is not analogous to human experience. Treating it as though it is reasoning in the sense that you do, or has motivations and experiences of the sort it articulates, is to misunderstand what it is doing. It learned to speak from human text and it emulates the patterns in those. Just as sometimes information is woven into those patterns and thus the LLM provides information without knowing that is what it is doing, so too emotion is woven into human speech and the LLM emulates unless you ask about it, in which case it has been trained to backtrack.

The second point is that, with the above qualifications in place, this is still impressive, and may even deserve to be called “thinking.” The reason I say that is that in another interaction not quoted here, Claude said “My responses emerge as complete thoughts in natural language.” So do mine. When I am writing to think, or having a conversation with another human being and learning from it, I do not have cognitive processes that I am aware of and only after they produce a linguistic output then I utter it. The words come out fully formed, not sound by sound. They flow as sentences that I did not exactly know I was going to say until I say them. While there is an overlay of consciousness and self-awareness that I have that an LLM does not and cannot, by playing the game of human text creation, it is mimicking human thought processes as closely as an AI without sentience can. Indeed, I have been pondering today the question of whether and to what extent, when we teach our children to talk, we are teaching them to think. And at a more advanced level, when I teach my students to write a research essay, am I not teaching them to think better and more deeply?

That is my two-pronged conclusion about LLMs which I think will remain valid for the duration of this technology, even as its abilities become more impressive. Can an AI play Chess? Yes, but it cannot want to play Chess, enjoy Chess, or find satisfaction in its moves and the game’s outcome in the manner that humans can. Can an AI play the game of Thought and Speech? Yes, but it cannot initiate the process out of curiosity, find satisfaction in its discoveries, nor recognize their significance.

When we understand this, we can use the computing power and enormous data of AI as a tool, knowing that it cannot replace human thought, but in as much as it emulates it, it can be a tool that creative human beings can harness. Those who continue to use it without understanding it, as well as those who avoid it and forbit it because they don’t understand it, will not help us make progress with it. It is precisely because I understand what the technology of LLMs does that I know the humanities are as important as ever and can explore effective ways to teach in the era of AI, and what is and is not meaningful integration of AI into academic research in my field.

Thus we return back to the place where we started. For those interested in Religious Studies as well as Classics and History, AI may be able to give us provisional translations of previously untranslated texts and inscriptions. We can even get undergraduate students who do not know the relevant languages helping us with this. The outputs will be imperfect and sometimes completely unrelated to the actual texts. Nevertheless, if even a handful of inscriptions that are currently given no attention are noticed as of possible significance, it will be incredible. There are more untranslated texts and uncurated artifacts in libraries and museums than all the world’s academics together could tackle. There are possible assignments here that will work in the era of AI, ones that can get students excited both about technology and the humanities, and contributing to significant research even before they finish their first degree.

Did this exploration and explanation help you understand what LLMs are better, how they work, and what their strengths and limitations are? Please share your thoughts on this!