“The Gods are not to be represented in the form of man or beast, nor are there to be any painted or graven image of a deity admitted.”

At first Numa’s prohibition might appear to derive from another religious tradition, not the tradition of Rome where images of the Gods once abound. In fact, this restriction relates to the very conception of the Gods and how Their providence influences the world. Before waxing too philosophical into pagan theology, we can state that a shared tenet is that the Gods are ever near us, among us, and within us. The divine courses through all things, whether objects, actions, powers, or places. In some there is a greater presence of the divine, a type of beneficial power originating from a God or Goddess that is infused into a thing. The divine within ourselves is called the juno in a woman, and genius in a man. All animals and plants have their own unique genius as well; so do all things. Through the individual genius we connect with the divine around us. At times the Gods can increase the divine power in an object or a person, taking possession of the genius as an in spiritu. A thing may therefore act in unusual ways as a result of inspiration, as when a sibyl is filled with the divine power of a God or even an inanimate object may move under the volition of a God. Or a location, touched by a Goddess, Her beneficial influence still present even after Her departure, may grow unusually lush. Such a divine presence we call a numen (pl. numina).

A numen is not a divine being. It is not a God or Goddess. It is a power or force that extends from a divine source. We explain a numen in this way. Wherever we may be, we radiate energy. We may take a seat and notice the warmth of a person who sat there before us. We see the imprint of his feet and fingers, the fog of his breath and a stain on the window next to us where his cheek brushed against the glass, all residue of his presence. How much greater, then, is the power emitted by a God and that can reside in a place where He has been? Numina may increase over time through accretion resulting in a greater presence of the divine. Or the numina in an object or place may suddenly increase by the action of a God or Goddess. We may invoke the prowess of Hercules, for example, and through practice and repetition increase His numina among us to benefit our athletics. Sumanus might instead cast a lightning bolt down at night, or the numina of Jupiter might drive the snow, as Horace said, into a sparkling sheen like white marble.

“If ever you have come upon a grove that is thick with ancient trees which have grown far above their usual height, shutting out a view of the sky by a veil of intertwining branches, then the loftiness of the forest, and the seclusion of the spot, and your wonder at the thick unbroken shade in the midst of the open spaces, will elicit in you a sense of a divine presence (numen). Or if a cave, made by the deep erosion of the rocks, holds up a mountain on its arch, a place not built with hands but hollowed out into such spaciousness by natural causes, then your soul will be aroused by a feeling of religious awe (religio) at the existence of a God. We worship the sources of mighty rivers; we erect altars at places where great streams burst suddenly from hidden sources; we adore springs of hot water as divine, and consecrate certain pools because of their dark waters or their immeasurable depth (Seneca, Epist. 41.3).”

It is this concept of the power of the Gods affecting the world around us through numina that governs both the use of natural things bearing a power of a God or Goddess and the non-use of artificial objects that are only anthropomorphic representations of a God. Nature, imbued with the Gods, is the best representation that we can focus on with reverence for the Gods. The very first temple at Rome was an oak tree that stood on the Capitoline Hill. Romulus dedicated this oak to Jupiter Feretrius (Livy 1.10). Individual trees and groves of trees acted as the earliest sanctuaries in Rome solely because the numina found within them were believed to be greater than usual. On the Esquiline Hill stood a grove of beech trees which was dedicated to Jupiter Fagutalis. The Locus Larum was a grove of oaks sacred to the Lares. Myrtle was sacred to Venus, and also to Ceres, a variety of oaks were held sacred to Jupiter, the olive to Minerva, the dogwood to Apollo, the black poplar to Hercules, and the yew to Dis Pater (Pliny 12.2; Ovid Met. 2.234; etc). One such grove, at the foot of the Capitoline Hill was dedicated to Carmentis by Numa Pompilius. It was in this sacred grove of Carmentis that Numa performed incubation rites and consulted with Egeria. Through her instruction Numa consulted with other Gods to learn what rites to establish for Rome . Most specifically attributed to Numa Pompillius were the sanctuaries and rituals held for Vesta, Fides, Carmentis, Jupiter Elicitor, and Mars. Even into historical times the cultus for these deities was performed without anthropomorphic images. Instead they relied on the actual presence of the God or Goddess, whether in sacred objects or sacred places.

In the Temple of Vesta, the presence (numen) of the Goddess appeared in the living fire tended by the Vestal Virgins. Images of the Vestal Virgins appear on Roman coins, where they are seen pouring libations from a simpulum before an altar. The Goddess appears in such scenes, if at all, as flames upon the altar. No anthropomorphic image carved in stone could truly represent all the complexity to the divinity of Vesta when She is already present in the hearth fire of the Vestals and in the hearth of every home.

In the ceremonies held for Fides held on 1 October, the flamines maiores bound their right arms in white cloth down to their figures and road hidden in a covered wagon, “because Fides ought to be veiled and hidden (Livy 1.27; Dion. Hal. 2.7; Serv. Aen. 8.636).” The flamines were dressed to show that they were pure and clean, and were carried under a veil to prevent pollution on their way to the ceremonies. While the Religio Romana requires a person to be clean and ritually pure before even attending ceremonies, and more so for sacerdotes and participants, extra care was taken in the ceremony for Fides because one must always be clean and pure in both body and mind before addressing the Goddess of Good Faith. The numen of Fides is ever present whenever two people extend their right hands to one another in good faith, to make a vow, to seal a contract or to confirm a treaty. She is the bond that builds society and Her numen is present among those who gather together in Her ceremonies.

From the Temple of Mars, in the Campus Martius, the lapis manalis was rolled up the clivus sacer with a thunderous sound to the Capitolium. In this way the Aquaelicium ceremony invoked Jupiter Elicitor to send rain. It called upon Jupiter in the sound made by the rumbling stone rather than with an image. It was a matter of sympathetic magic, the sound of thunder, artificially produced, to invoke the God of thunder and rain. But the idea behind it, that things holding the numen of a God could attract the God’s attention and thus used in rites to invoke a deity’s additional numina, is a concept basic to the practice of the Religio Romana. Each time incense is offered, the scent is intended to attract the deity. In much the same way, the Jewish texts instruct how sacrifices are to be offered so that the scent of burnt offering shall be “pleasing unto Andonai.” The same could be said of our own practice of burning an offering, but there is more behind the act of sacrifice than just to create a pleasant atmosphere to be enjoyed by cultores with the Gods. This concept of the numina in all things informs our practice of sacrifice as a means of giving back to a God or Goddess the divine essence in an offering. It informs us to approach an altar in reverence, where numina of the Gods meet with the numina of worshipers, and an accretion of numina build up with each touch of the altar. The altar itself, by what it contains, is thus more than just an image of a God.

Another way in which the concept of numina informs ritual practice is in fashioning images, although not in necessarily in anthropomorphic form. The fragrant cypress, its trunk formed into a pillar, draped with cloth, served as an early representation of Juno. Likewise a wooden pillar draped with the toga of Rex Servius Tullius represented his presence in as much as his toga still retained his numen. There was even a story of a miraculous event where his toga survived a fire even though the temple in which it stood burnt to the ground. In similar fashion, an iron spear kept in the Campus Martius Temple of Mars was believed to be so endowed with the numen of Mars that it would rattle whenever danger drew near to Rome. The sacred shield called the ancilla that Jupiter sent to Numa as a sign was another fashioned object, carried by the Salii priests of Mars on certain festival days in the month of Mars, which can be said to have represented Mars through the presence of His numen and without an anthropomorphic image. In each case the numen was found in the material from which the object was fashioned and not in its image. Later of course statues would be made, primarily as decorations, but when images were used in ritual it was the qualities of the material and the numina these possessed that could be sensed as a divine presence. The same ideas have carried over into the manufacture of Orthodox Christian icons where there is more to the process, and to the spiritual qualities infused in the materials of the work, than just the resulting image. You can find a similar concept behind the use of relics in Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Judaism. The concept of the divine extending spiritual power into objects and things is rather universal in religious traditions. Our focus in Roman ritual is on the Gods and the beneficial effect of Their presence among us. The form of an object, its appearance, does not matter so long as it serves to hold the presence of a divine numen.

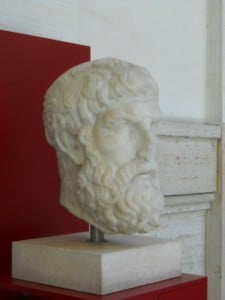

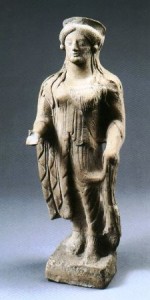

“Varro also tells us that the Romans worshiped the Gods without any images for a hundred and seventy years.” That is to say, not until 581 BCE during the reign of Tarquinius Primus, about the year that Tarquinius Superbus was born. This refers to the terra cotta statues that began to decorate temples built at Rome in a foreign manner. One example that has been found is the famed terra cotta grouping of Hercules and Minerva from the Sant’Omobono sanctuary, now housed in the Musei Capitolini. This life-sized grouping comes from the Temples of Mater Matuta and Fortuna in the Forum Boarium. Legend attributes these temples to Servius Hostilius who reigned between 579-535 BCE (Livy 5.19.6; Dion. Hal. 27.7). The statues of Hercules and Minerva, and another terra cotta grouping, date to the end of the sixth century instead, when the temples were remodeled shortly after the expulsion of Tarquinius Superbus. These groupings decorated the roof of a temple, and thus were not used in any ceremonies worshipping the Gods. Their location and the association with Servius Hostilius suggest that these were from an extramural sanctuary intended for foreign visitors and not really concerned with Roman ritual. However statues and images were eventually included in the Religio Romana, carried in processions, seated on couches during lectisternia when common people were allowed to approach. If at first the numina of the materials were held to be the true representations of a divine presence, or that a God might be induced to place His numen into a image in the same way He might be present in a tree or a stone, then eventually fawning over images as idols emerged as an influx of people from the East came to Rome.

Thus seen as abandoning the Numa Tradition, some among the Roman elite reflected on the early cultus that was still held in the worship of deities introduced by the pious Founder of the Religio Romana. “Had that custom been retained,’ said Varro of banning anthropomorphic images, “the worship of the Gods would be more reverently performed (Aug. Civ. Dei 4.31).” Modern cultores Deorum Romanorum may decorate their homes and altars with images. But in keeping with the Numa Tradition, they interact with the Gods through the numina in a sacrifice on the altar. The sacred altar fire, as the focal point in our rituals, we hold in the greatest sanctity as the place in which we meet with the Gods. The numina in an altar, however, only indicate the deity from whence they came, and thereby lead us back to their divine source. Aware of the presence of a God among us during ritual, we therefore adopt an attitude of sincere reverence when approaching the Gods. These three things – Focus, Source, and Attitude – characterize Roman rites, and thus Numa forbade images that might distract our attention away from our focus and away from the divine source. In this way he prohibited superstitio and promoted religio with a respectful and reverent attitude