“Numa appointed Numa Marcius, son of Marcus, as pontifex from among the patricians. He gave him full solemn written instructions about the ceremonies, specifying for each sacrifice the proper offerings, the proper days and the proper temples and the way in which money should be raised to meet the expenses (Livy 1.20).”

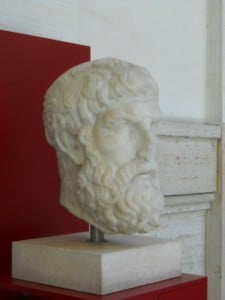

The instructions of Numa the Lawgiver were said to have been written down under the direction of Postumnius, following in the wake of the Gallic sack of Rome in 390 BCE. Then, in 181 BCE, Numa’s stone sarcophagus was discovered on the Janiculum Hill. Buried along with Numa were seven books on pontifical law and seven books on Greek philosophy. (Others say as few as three books total and as many as twenty-four books, twelve each on law and philosophy.) The latter were burned by praetor Quintus Petilius, Greek philosophy being considered dangerous at the time, however Numa’s books on lawwere incorporated into the Libri pontificii. The books on pontifical law were said to contain information on the names by which the Gods were to be called, the special prayers used to invoke Them, what was proper to offer Them, and what was prohibited, where to offer sacrifices specifically to one deity or another, on what days, and in what manner. The Libri pontificii also recorded events that occurred from year to year, concerning prodigies, special religious ceremonies, the death of priests, and the appointment of their replacements, among other events. In other words, the Libri pontificii were the sacred texts of the Religio Romana.

In the fourth century CE the Libri pontificii were unfortunately burned by the Christians. Today there is even a fresco in the Baptistery behind St. John’s Lateran Church in Rome, which still celebrates the destruction of our sacred texts. The Libri pontificii may have been comparable to those found in another Mediterranean tradition, that of Judaism. However, the Jewish texts of Vayikra (Leviticus), Bamidbar (Numbers), and Deuteronomy, as well as such books as the Damascus Document, the Temple Scroll, Book of Jubilations, and commentaries in the Mishna only refer back to the cultus of a single temple. Like the laws of Numa, these Jewish texts set out what animals are to be sacrificed, along with what amounts of wine and flour, on what occasions, and where, and for what offenses these sacrifices are required. At Rome there was not just a single temple, however, but hundreds, with every temple, fanum, sacred grove and altar each having their own individual laws, and these various leges templi we are told conformed to the laws previously set down by Numa Pompilius. Today all that remains of the Librii pontificii are a few fragments found in later commentaries that quote from Annales by various authors, all based on these sacred texts. These are supplemented to some extent in inscriptions bearing leges templi, as seen, for example, on the tablets found in the sanctuary of the Fratres Arvales outside Rome. From such tertiary Roman and Greek sources we can glean some of the laws attributed to Numa. Here I paraphrase some of those laws that relate to sacrifices.

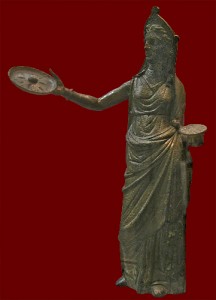

“The Gods are not to be represented in the form of man or beast, nor are there to be any painted or graven image of a deity admitted (to your rites) (Plutarch Numa 8.7).”

“Sacrifices are not to be celebrated with an effusion of blood, but consist of flour, wine, and the least costly offerings (Plutarch Numa 8.8).”

“No sacrifices shall be performed without meal (mola salsa) (Plutarch Numa 14.3).”

“When celebrating the harvest, pour a libation to the Gods before you eat (Censorinus, De Die Natali 1.8-10).”

“No fish that is without scales shall be served up at the Festivals of the Gods lest they pollute the sacrifice (Hemina Annales apud Pliny, N.H., 32, 2, 20 ; Cf. Fest., F. 253).”

“You shall not pour libation to the Gods of wine from an unpruned vine (Plutarch Numa 14.3).”

“When you sacrifice to the celestial Gods, let it be with an odd number; when to the terrestrial, with even (Plutarch Numa 14.3).”

“If anyone offers sacrifice different (from what is vowed, or what is prescribed), may he be consecrated himself as a sacrifice to Jupiter (Fest., P. 6).”

“If anyone should happen to offer a bull to Jupiter, let him make an offering in expiation (Macrobius, Saturnalia 3.10.7).”

“Turn round to pay adoration to the Gods; sit after you have worshiped (Plutarch Numa 14.3).”

“Let no paelex touch the altar of Juno; if she touches it, let her, with her hair unbound, offer up a female lamb to Juno (Fest., P. 222, Paelices ; Cf. Gell., 4, 3, 3).”

“This also is instituted by Numa, that sacerdotes not shave with iron but with bronze implements (Lyd., Mens., 1, 31).”

The challenge for today’s sacerdotes is to interpret, explain, and put into practice these and other laws Numa handed down, in order to inform a new generation of cultores Deorum Romanorum on the practice of the Religio Romana with sincere reverence for the Gods in a modern world. Therefore I shall offer some comments on individual laws of Numa in my following posts.