by Andre E. Johnson and Anthony J. Stone, Jr.

by Andre E. Johnson and Anthony J. Stone, Jr.

On April 4, 1968, on a balcony at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee in front of Room 306, an assassin shot and killed the nation’s prophet of non-violence. The previous night, not feeling the best and against his own wishes, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. reluctantly showed up at a rally supporting the striking sanitation workers at Mason Temple Church of God in Christ where he delivered a speech for the ages. King somehow mustered up enough strength to move the crowd that night, calling them to stand firm under the oppressive tactics of the Henry Loeb administration. He also called for them to turn up the pressure in their non-violence resistance. This meant massive economic boycotts. He asked them not to buy “Sealtest milk” and “Wonder Bread or Hart’s Bread.” It was time for the redistribution of the pain that the sanitation workers have only felt. “We are choosing these companies,” King declared, “because they haven’t been fair in their hiring policies, and we are choosing them because they can begin the process of saying they are going to support the needs and the rights of these men who are on strike. And then they can move on — downtown and tell Mayor Loeb to do what is right.”

He further called his audience that night to “strengthen Black institutions.” He wanted them to deposit all of their money in Tri-State Bank and called for a “bank in” movement in Memphis. “Put your money there,” he declared, “you have six or seven Black insurance companies here in the city of Memphis. Take out your insurance there. We want to have an ‘insurance-in.’” He proclaimed,

We don’t have to argue with anybody. We don’t have to curse and go around acting bad with our words. We don’t need any bricks and bottles. We don’t need any Molotov cocktails. We just need to go around to these stores, and to these massive industries in our country, and say, “God sent us by here, to say to you that you’re not treating his children right. And we’ve come by here to ask you to make the first item on your agenda fair treatment, where God’s children are concerned. Now, if you are not prepared to do that, we do have an agenda that we must follow. And our agenda calls for withdrawing economic support from you.

But on the next day, King laid dead on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. Earlier that day, he had worked on his sermon for Sunday, April 7, which was Palm Sunday. Typically, on Palm Sunday, church audiences hear the sermon about Jesus coming into Jerusalem on the back of a donkey and shutting down all traffic. Christians call this the Triumphal Entry; where Jesus lead a processional in which folks waved palm branches and proclaimed, “Hosanna, Hosanna, blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!” Even for non-liturgical churches like many Black Baptist congregations, Palm Sunday is usually celebrated. However, King’s sermon was not your typical Palm Sunday variety. Though he lay dead, his associates found in his pocket the sermon notes he would have

preached that Sunday if he had lived. The sermon title:

“Why America May Go to Hell.”

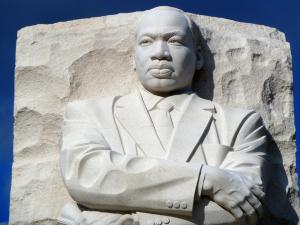

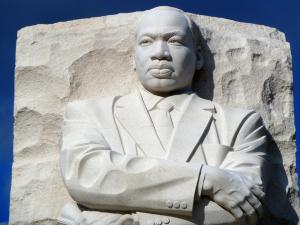

While King today is largely considered one of the greatest Americans to ever live, during his lifetime—and especially near the end of his life—King was one of the most hated men in America. The FBI named King “the most dangerous Negro in America.”

According to a 1966 Gallop Poll, almost two-thirds of Americans had an unfavorable opinion of King—a twenty-six-point increase from 1963. Scholars note that hostility toward King increased shortly after the passage of the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 at the time when many white Americans believed that integration was moving too quickly. Furthermore, for much of the last year of his life, King spoke out against US political institutions for what he argued were immoralities such as the war in Vietnam, lack of acknowledgment and/or support for the economic downtrodden, and especially the institution of racism.

If this version of King comes as a surprise to many of his contemporary admirers, it may be because of the shift scholars have noticed in King’s rhetoric over time. According to

Sunnemark, pre-1965 King had what he called a “common discourse.” For him, this common discourse of King was as “inviting as possible for as many as possible.” King meant this type of discourse to be non-offensive as the rhetoric was mostly about “recognition and affirmation.” When employed today, it works in the same way. “The vague generality,” writes Sunnemark, “means that King’s rhetoric can still be filled with meaning from different sources. It can still conform to a particular identity of traditional American ideology and self-understanding and its system of signification has become tied in with this identity.” In other words, this “vague generality” helps us to understand how both progressives and conservatives can easily appropriate King’s earlier rhetoric and discourse. Further, he maintains that this is how King has become frozen in time with his “I Have a Dream” speech. The speech, argues Sunnemark, has become a signifier of righteousness which means people can use it in a “wide range of circumstances for a variety of means.”

However, King’s later rhetoric is not available for use in this manner, and it is this rhetoric that we examine. We especially focus on one of the main reasons that many celebrate King today—his seemingly or supposed color-blind, equality-based rhetoric. Along with

Cook, we suggest that King, in the last year of his life, began “to understand the hegemony of repressive ideologies, and to deconstruct the limits they appear to set on the possibilities of change” and became “deeply committed to the reconstruction of a social reality based on a radically different assessment of human potential.” When examining King’s rhetoric during the last year of his life, one would note that several of

his last speeches addressed the fallacies of white hegemony; the political elitism and institutional racism of America; the Johnson administration and foreign policy (especially the war in Vietnam), and the redistribution of economic resources—poverty and the treatment of workers. However, we argue that the foundation of these arguments is King’s growing understanding of race and racism. In short, as a key component of these speeches, King focuses much more on race than modern admirers would have imagined.

We also note that for King to move rhetorically in this manner was not politically expedient. He had secured victories in getting the Johnson administration to pass the long-awaited Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965. King had an ally in the White House and, politically, it did not make sense for King to take such controversial positions. However, we submit that it only makes sense that he did begin to address America’s racism because King adopted a prophetic persona of a pessimistic prophet. More specifically, when we frame King as prophet, his rhetorical shift becomes understandable.

To highlight his prophetic pessimism, we examine King’s rhetoric during the last year of his life (April 4, 1967-April 3, 1968)—focusing specifically on the issues of race. In examining several texts of King, we attempt to highlight King’s directness and firmness when addressing the race issue; we also approach an analysis of the rhetoric used by King in his attempt to dismantle hegemonic politics and institutional racism. Specifically, we argue that while Martin Luther King was radically dismantling white hegemony; he was also becoming one of the most hated men in America.

Donate to the Work of R3

Like the work we do at Rhetoric Race and Religion? Please consider helping us continue to do this work. All donations are tax-deductible through Gifts of Life Ministries/G’Life Outreach, a 501 (3) tax-exempt organization, and our fiscal sponsor. Any donation helps. Just click

here to support our work.

by Andre E. Johnson and Anthony J. Stone, Jr.

by Andre E. Johnson and Anthony J. Stone, Jr.