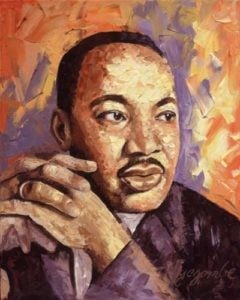

On April 4, 2018, America commemorated the 50th year anniversary of the death of Martin Luther King Jr. The social media landscape was full of think pieces, editorials, long-form essays and reflections that centered on the life and legacy of America’s prophet of nonviolence. News stations and newspapers from all around the world produced stories and interviewed people who lived during King’s time and those who did not. However, much of the commemoration focused on the memory of King and how his words continue to shape and frame our current challenges and problems.

On April 4, 2018, America commemorated the 50th year anniversary of the death of Martin Luther King Jr. The social media landscape was full of think pieces, editorials, long-form essays and reflections that centered on the life and legacy of America’s prophet of nonviolence. News stations and newspapers from all around the world produced stories and interviewed people who lived during King’s time and those who did not. However, much of the commemoration focused on the memory of King and how his words continue to shape and frame our current challenges and problems.

Anticipating the conversations that would take place during the 50th year commemoration, I thought that a journal in our discipline should devote a special issue that examines the rhetoric of King. I thought this would give scholars in our field an opportunity to (re)discover the rhetoric of King and to study one of America’s finest orators. It would also give us the opportunity to add to what is a surprisingly small collection of scholarship solely devoted to the rhetoric of King. To give a comparison, a search in the Communication and Mass Media index reveals a shocking discovery. Since his assassination in 1968, only thirty-five articles examine the rhetoric of King. Compare this to articles examining the rhetoric of President Barack Obama. Since 2005, seventy-nine articles examine the rhetoric of Obama. Therefore, despite Edwin Black’s observations that King left a very “considerable body of written work—speeches, articles and books” and that King’s “influence on the character of public persuasion is by itself sufficient to regard King’s rhetorical efforts as revolutionary,” the dearth of scholarship in rhetoric on King speaks volumes.2

However, I did not want to lock King in the past. The commemorations that occurred throughout the world pointed to contemporary understanding and meanings of King’s rhetoric. We wanted essays that would not only ground themselves in the rhetoric of King but also point to his legacy 50 years later after his death. We looked for essays that centered on people, groups or institutions that draw inspiration from King’s rhetoric. In short, in this special issue, “From the Mountain Top and Beyond: Contemporary Meanings and Understandings of the Rhetoric of Martin Luther King Jr., 50 Years Later,” we sought to connect the historical to the contemporary to show the vibrancy of King’s rhetoric and how people interpret that rhetoric today.

The idea for this special issue came to me while teaching a graduate seminar on King’s rhetoric. As we focused on the last year of King’s public discourse, I begin to see and understand the shift in King’s rhetoric. As Sunnemark noted in his study of King, the pre-1965, King had what he called a “common discourse.” According to Sunnemark, this was an “inviting discourse,” focused on “recognition and affirmation” that was meant to be “non-offensive” to as many people as possible. This, argued Sunnemark, opens the rhetoric to multiple interpretations when employed today. “The vague generality,” wrote Sunnemark, “means that King’s rhetoric can still be filled with meaning from different sources. It can still confirm a particular identity of traditional American ideology and self-understanding and its system of signification has become tied in with this identity.” He further maintains that this is how King has become frozen in time with his “I Have a Dream” speech. The speech, argues Sunnemark, has become a signifier of righteousness which means people can use it in a “wide range of circumstances for a variety of means.” However, according to Sunnemark, King’s rhetoric later in his life “is not available for use in this manner.” He argues that since King’s transformation meant the “gradual disintegration of the Civil Rights movement discourse,” one cannot fill it with different kinds of meaning in the same way his one could fill his earlier discourses. For Sunnemark, his later rhetoric poses a grave challenge and makes an accusation, and that is much harder to handle and use than an affirmation.” So to compensate for this, we tend to misread King’s rhetoric during his later life.

I argue that this misreading of King’s later rhetoric, especially in the last year of his life, leads to a misremembering of King’s legacy and the challenge that King left.

Read the rest here.