For yours is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, now and forever. Amen.

We have been asking throughout this series on the Our Father what are we finally seeking by praying these seven petitions.

Essentially, we have prayed for our Father’s kingdom against our own; for his will against our own desires. We have prayed for his bread, that we may glimpse creation’s wounded splendor in a life marred by sin.

We have prayed for his forgiveness, while promising ours for the neighbor. We have sought protection against sin and evil, from the swirling trials of temptation toward false belief and despair.

Now we arrive at the Doxology, that part of the Our Father which is not part of the Our Father.

Where did it come from? Not from the Bible.

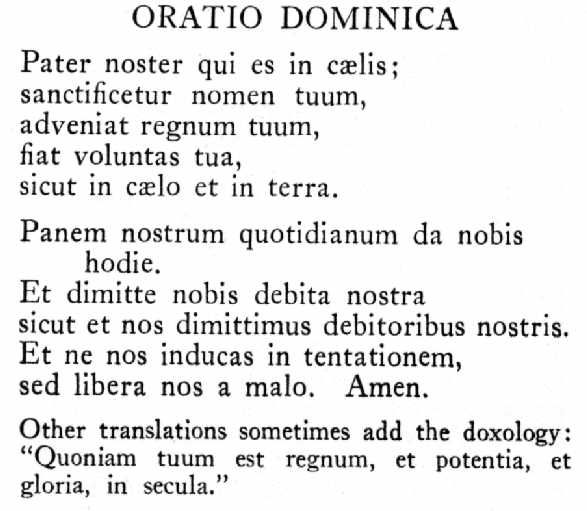

Some late manuscripts of Matthew’s 6th chapter record the Doxology as the words of Jesus, but none of the earliest do. Th e earlier a manuscript can be dated, the more it is regarded as more reliable than anything contained in later versions. Well, if the Doxology does not belong to the earliest copies of Matthew, why is it there? Probably because Christians were already praying the Doxology and a later copyist decided its absence was a mistake. So he put it in.

e earlier a manuscript can be dated, the more it is regarded as more reliable than anything contained in later versions. Well, if the Doxology does not belong to the earliest copies of Matthew, why is it there? Probably because Christians were already praying the Doxology and a later copyist decided its absence was a mistake. So he put it in.

Some few contemporary translations still carry the Doxology but most, including the New American Bible Revised, now omit it. So it isn’t in the Bible.

Still, there is evidence that it was in early Christian usage. Possibly it was an oral addition before any of the Gospels were written. The Our Father can be found―for the first time we think―in an early mid-first century document called the Didache (“the teaching”). It repeats Matthew’s version and it includes the Doxology.

The Didache is mentioned in Eusebius’ The Church History (roughly AD 325), and some few Church Fathers thought the Didache belonged in the New Testament.

Intriguingly, some scholarship (though very little of it candidly) points to its possible composition as a result of the Apostolic Council (Acts 15:28), a further instruction for Gentiles coming to what hitherto had been a Jewish Church. That would be around AD 50 (only seventeen or so years after the Resurrection and still twenty years before the first gospel, St. Mark’s).

The Didache was a catechism, a liturgical guide for baptism and Eucharist, and a manual on Christian ethics. The year 50 would also make it the earliest work where Lord’s Prayer appears with the Doxology. This would also tell us that the Our Father and Doxology formed some part of the Church’s earliest oral memories of Jesus.

But if it wasn’t properly part of the prayer Jesus taught, why is it there at all? I’d guess because Christians added it just because it sounded right.

The Doxology is included in the mass, of course, but not directly as part of the Our Father itself. That’s how we know Catholics are different from Protestants. Catholics pause for the priest to interject a petition; Protestants push on.

The Didache, however, instructs Christians to say the Our Father three times daily, morning, noon, evening; Doxology included. Hankering for some of that old time religion one hears about, there it is.

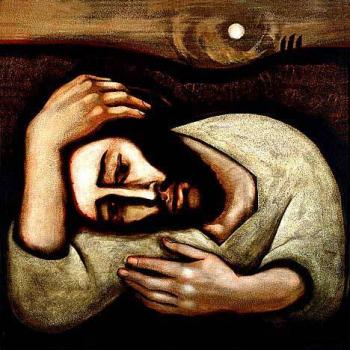

Just as the empty tomb compels us to think about life in a world where Christ is raised, the Doxology of the Our Father confronts us with the kingdom, the power, and the glory that belongs to the Father who raised our Lord Jesus Christ from death.

It is a bold declarative explosion of praise to the Most High God of Israel who―through Jesus―now encourages us to address him as “our Father.” The words introduce nothing new to the prayer we pray. But they will make us think.

We have to ask what these are, given the resurrection of the crucified Christ, this kingdom, this power, this glory.

Most obviously the kingdom, the power, the glory are not ours. We are relieved from the arrogance of building my kingdom, my power, my glory, all for me.

That means God’s kingdom, power, and glory are unutterably different from anything we might suppose or reasonably imagine. Remember, we are warned never to think God is like us. (Ps. 50:21) That is a chastening thought.

God delegates himself by Christ for humanity and becomes derelict, abandoned to the cross. When we think of kingdom, and power, and glory they must be viewed in a sense that defies human comprehension, except as seized by faith.

God’s kingdom? It is on the cross, in a ruined man next to a thief who becomes the first subject of Christ’s kingdom? (Lk 23:42)

God’s power? Isn’t that Christ lifted up to a cross from which he will draw all people to himself, “indicating the manner of his death”? (Jn 12:32-33)

God’s glory? Is that Christ carrying unto Resurrection the wounds received from crucifixion? (Jn 20:27)

The Doxology properly is how the Our Father ends and it is one reason we dare to say in the very first place, “Our Father.”

Russell E. Saltzman lives in Kansas City, Missouri. His latest book is Speaking of the Dead. He can be reached at [email protected] and on Twitter @RESaltzman.