This is the second article of a three-part series proposing a brand-new atonement theology. Follow this link to read part 1.

Over the past several weeks, much of the content in the articles I have written has been tangentially connected to atonement.

Atonement is a theological explanation for how we are saved from our sins.

Last week, I explored how many contemporary atonement theories are woefully inadequate, and do not provide explanations consistent with scripture or human experience. Indeed, atonement is a confusing mystery to the average believer today, and that unfortunately includes both clergy and theologians as well.

I know this, because for the past year I have committed myself to extensive research specifically regarding what people believe and understand about atonement. From these considerations, I have formed six non-negotiables that serve to inform what a new atonement theology should and should not look like:

- A theology of atonement must fit the narrative advanced by the New Testament: A holy God acts to restore a loving relationship with his creation.

- Atonement cannot be transactional because that is inconsistent with God’s unconditional mercy, so…

- Any theology of propitiation is flawed because it presupposes God may only act in a loving way by some mechanism of human action—which is contrary to any theology of divine plenary love.

- Likewise, the relational dynamic cannot be devoid of humanity. We are not victims of circumstance, nor are we mere pawns. Atonement must require human responsiveness, or it is not relational.

- Atonement must provide a purpose for Christ’s death—otherwise his act of self-sacrifice has no purpose.

- Atonement must reckon our forgiveness in the context of Christ—otherwise, Christ could not have been who he said he was, and his actions cannot provide salvation.

Although no extant historical atonement theories fulfill all those requirements, one in particular does propose ideas that should be examined for context before proceeding to formulate a brand new atonement theology.

Irenaeus’ “Recapitulation”

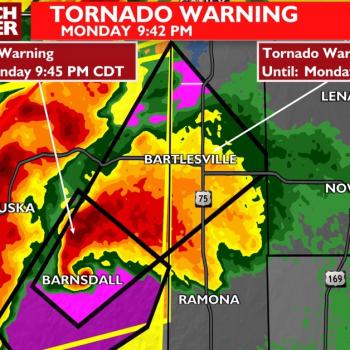

An early church father just two generations removed from the apostles named Irenaeus developed a theology of atonement called Recapitulation that offers an explanation for the cross within a narrative of unlimited mercy juxtaposed against the original sin of humanity.

Classical Irenaeun Recapitulation atonement begins with envisioning Christ as the new Adam, and thus by living a sinless human existence, Jesus restores humanity from the destruction of original sin. Where humanity has been unfaithful, Christ was faithful even unto death on the cross.

“Recapitulation” is an English translation of the Latinized form of anakefalaiosis (ανακεφαλαιωσης), which most literally means “to find a new head”. The implication is that humanity has a new identity in Christ as opposed to Adam. Though Iranaeus likely used the Greek ανακεφαλαιωσης, this definition is further deepened by how it is understood in Latin (and Irenaeus was fluent in both languages): “recapitulans” was a term used in rhetorical speech meant to designate a final summation, such as how an attorney employs a closing argument to conclude a case before a jury. The interesting part is not that repetition is integral to understanding the meaning of the term, but that this act finalizes or completes a process.

Irenaeus believed by Christ’s incarnation, death, and resurrection, humanity was born again. Instead of suffering death because of original sin, those who participate in new life in Christ are redeemed by the same power that resurrected Christ—that as he conquered death, so may we.

Now, Recapitulation isn’t bad theology, but it remains underdeveloped over 1800 years since it was first considered. There are also elements Irenaeus incorporated (such as comparing Mary the mother of Christ to Eve) which serve no purpose in a theology intended to address atonement alone.

Qualified Restoration Atonement

After quite a bit of study and prayer, I would like to propose an atonement theology I call Qualified Restoration that differs from and builds upon what Irenaeus advanced.

Similar to anakefalaiosis (ανακεφαλαιωσης), which is an extrabiblical term, apokatastasis (αποκατάστᾰσις) means “restoration, or re-establishment.” As with recapitulation, apokatastasis is often used to communicate the concept of restitution. In fact, the word as used in the NT is translated in Latin (Vulgate) to “restitutionis,” the genitive form of a noun often defined in ancient legal documentation as, “a command given with authority by which the possession of a thing taken away is restored to a person.” The term is found in Acts 3:21 in a sermon spoken by Peter, commonly translated in English as “restore:”

“Heaven must receive him [Jesus] until the time comes for God to restore everything, as he promised long ago through his holy prophets.” (Acts 3:21, NIV)

Though the context of this usage does not specifically concern atonement, it still describes God taking restorative action for humanity.

The term apokatastasis is also found in the Septuagint (an authoritative Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible), in Malachi 4:6 replacing the Hebrew verb “shub” (שוב), which is a common word meaning “to turn back, or return.” As with its usage in Acts, though specifically unrelated to atonement, the passage describes God taking action to restore humans.

Early Church fathers actually argued about the NT context of apokatastasis because some believed it could imply universal salvation (Origen in particular). Though what I propose within the context of atonement does not address this well-documented controversy, because my intended use of the term “restoration” is wholly grounded in the biblical usage of apokatastasis, I have added the adjective “Qualified” to clearly distinguish my theology as consideration of atonement alone.

“To Finally Raise Back Up”

Apokatastasis is the inspiration for my Qualified Restoration atonement theology for other textual reasons as well.

Based on “apokathístēmi” (ἀποκαθίστημι), when we break down the word, “apo-“(ἀπο-) is a prefix meaning “to move away or apart” and also indicates the following action is “conclusive” or “finished”—that the motion is a means to an end. The next part is compound: “-kata-“ (κᾰτᾰ) means “down” or “back,” and “-hístēmi“ (ἵστημι) “to establish, set up, or cause to rise.”

As you can see, while combining these ideas does perfectly equivalate “restoration” in the most simple of terms, the word also offers a much more robust definition. I suggest “to finally raise back up” encompasses each part of the word, and (equally important) is evocative of scripture passages that describe God acting to restore humans. For example, take Psalm 40:1-2a (NIV):

“I waited patiently for the Lord;

he turned to me and heard my cry.

He lifted me out of the slimy pit, out of the mud and mire;

he set my feet on a rock and gave me a firm place to stand.”

Similarly, as Christ declared, “It is finished” on the cross according to John 19:30, my definition accounts for Qualified Restoration to finish or finalize the sin problem—without propitiation.

Atonement Is Not Propitiation

Your chosen English biblical translation has about a 50% chance of the word “propitiation” being used in 1 John 2:2 and 4:10. The Greek word “hilasmos” (ἱλασμός) that is used also has cognates that are likely similarly translated in Romans 3:25 and Hebrews 2:17. Every one of these usages regard atonement.

For better or worse, translators who believe in propitiation translate “hilasmos” and its cognates that way—and no one else anywhere does (except maybe Plutarch’s “conciliate” in one single instance). My go to Louw and Nida Greek-English Lexicon translates it as “the means of forgiveness.”

Why? Context matters.

Zero of the Septuagint (LXX) usages of hilasmos could be interpreted to mean “propitiation.” In each and every instance, it describes something that changes humans rather than something that changes God—and that is the crux of the matter:

Propitiation is bad theology because it proposes God must change due to our sin, rather than requiring human transformation.

One concept Irenaeun Recapitulation atonement suggests but never explicitly states is a foundational element of Qualified Restoration atonement: The consequences of sin (death) are not imposed by God, but naturally flow from the destructive force of sin because it is an absence of God’s holiness—the love and life he is that gives us life. Death isn’t a punitive measure by design—it is a vulnerability exposed by human knowledge of good and evil, a weakness humanity never would have encountered was it not for The Fall.

There are many scriptures in the New Testament such as Romans 5:8 and 1 John 4:9-10 which establish an atonement narrative around God’s love. Specifically, “while we were still sinners” and “this is love…that he sent his Son.”

So, what is the context of hilasmos in the New Testament?

The answer is simple: atonement.

In fact, in every case, the word could easily be translated as “atonement.” And that is exactly what the New International Version (NIV) does, along with the NLT, BSB, CSB, Par (Aramaic Bible in Plain English), ISV, MSB, NET, NRSV, WNT, WEB, and many other English translations.

More to Come

I have just scratched the surface of what I plan to share about Qualified Restoration atonement. My next article will cover more ground, and venture into deeper theological waters.

In the meantime, here is a précis of Qualified Restoration that also incorporates the definition of sin that I proposed in February:

Qualified Restoration Atonement

Knowledge of good and evil exposed humanity’s vulnerability to sin, a pervasive attraction to evil that deprives us of holy connection with God, resulting in our certain death.

In a mission of love and mercy, God sent his Son, Jesus, so that we would believe in him and be raised up from the depths of sin and death to salvation. Likewise, Jesus acted selflessly and died willingly on the cross as a holy sacrifice, then was resurrected so that we might have faith and be saved.

When we respond to Christ’s death and resurrection with faith in him, we also accept God’s graceful gift of forgiveness and everlasting life, and the Holy Spirit births in us the love of Christ. The holy presence of Christ living in us not only cleanses us from sin but also reconnects us with God, finally restoring humanity to a loving relationship with our creator as a new creation.