Back in February, Sen. Marco Rubio explained why he opposed the Violence Against Women Act:

I could not support the final, entire legislation that contains new provisions that could have potentially adverse consequences. Specifically, this bill would mandate the diversion of a portion of funding from domestic violence programs to sexual assault programs.

Rubio has this idea, apparently, that different types of abuse have nothing to do with one another. Not a surprising conclusion in a world that’s determined to paint all abuse as isolated incidences committed by monsters, but that’s not reality. Often, sexual abuse is present in violent relationships.

No one wants to talk about the fact that different types of abuse are connected because that means challenging the very society–ripe with hierarchies that enforce themselves with violence–that we live in.

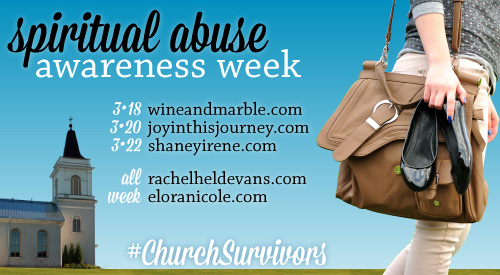

Today, I’m discussing spiritual abuse as part of a Spiritual Abuse Awareness Week that some fellow bloggers are hosting. Also this week, Rachel Held Evans will be hosting a more general discussion of abuse (which I will be guest posting for) and Elora NIcole will be sharing the anonymous stories of survivors.

With all these thoughts of abuse in general going through my head, I think about how ridiculous statements like Rubio’s sound. As if we can end violence against women without ending sexual assault.

Truth is, the violences that women (and other oppressed groups) face often stem from the same root–a deeper violence that questions the legitimacy of their very humanity.

I don’t want us to miss this point while we talk about the different types of abuse that people face, inside and outside of the church. Abuse happens, and society either ignores or accepts it because there is an assault on humanity that says certain bodies are objects, or are public property. An assault that paints some bodies as worthless, gross, weird, animal-like, sinful, collateral, too sexual, needing to be taught a lesson, etc.

Religion is far from the only institution that perpetuates this kind of abuse, but spiritual abuse can be a powerful tool for painting some groups as less important than others and therefore “deserving” of violence.

This happens in obvious cases such as the Southern Baptist Church supporting the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, or in the many church groups that advocate hitting children who misbehave.

It also happens more subtly in ways that I don’t think most leaders (though when you hear stories like Jack Schaap’s, you wonder…) or church members intend.

Here’s where my own story comes in. I grew up in church and grew up learning many things about myself and about my body and about the way the world is. I also ended up in an abusive relationship when I was 16.

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about how I was physically, verbally, and sexually abused in that relationship, but little thinking about how I was spiritually abused. My ex-boyfriend used my own deeply-held religious beliefs to make me think that what he did to me was okay. It was easy for him to convince me, too, because I had been absorbing abusive ideas from the churches I’d attended my whole life.

I will be writing in more detail about how my idea of who God was affected what I accepted as love. But my churches growing up also fed me dangerous ideas about who I was, what my body was, and what my place in the world was.

I was a woman, the church told me, so I had to be passive, meek, submissive, caring and nurturing, and endlessly patient and forgiving. A man, on the other hand, was just naturally aggressive, out-of-control, and sexual. These were God-given traits.

My abuser, knowing this, played on those, even sometimes calling my relationship with God into question when I didn’t live up to my role.

My church also taught me that I was worthless. From the sermons the pastors preached to the books that my youth pastors recommended. Because I was not a virgin I was what the Christian dating book, Dateable, would call “dollar store leftovers.”

My abuser, knowing this, told me constantly that no one else would want me so I had better stay with him. That I was already impure and couldn’t be fixed so I might as well let him do whatever he wanted with my body.

My church taught me that I was responsible for men’s actions. That dressing immodestly could make men lust after me.

My abuser, knowing this, blamed me when he sexually assaulted me. He told me it was my fault for being too sexy, even in the Baptist school-approved outfit I was wearing.

All violence is connected.

I’m positive that the churches I grew up in did not want their teachings to be used by abusers to support abuse.

Too bad. That’s not how it works.

Those teachings were violence in and of themselves. They did violence to my humanity. And in doing that violence to my humanity, they sent the message to abusers that I did not have to be treated as human.

Churches don’t have to be as cult-like and controlling as Driscoll’s Mars Hill or First Baptist Church of Hammond to be abusive. By using language about groups–whether it’s women, children, LGBT people, or people of different colors, cultures, countries, or religions–that does violence to their humanity, they commit spiritual abuse. And spiritual abuse won’t confine itself to the pulpit. Those abusive words and teachings and ideas leave the church in the hearts and minds and Moleskine notebooks of every church member and are spread throughout society like an infectious disease.

The church is not the only source of this disease, again, but it is a powerful one because battling it means battling ideas and perceptions about God (something I will discuss more in my guest post for Rachel Held Evans later this week).

A church that claims to worship a man whose purpose was “to set the oppressed free” should be horrified to learn that its teachings are being used by abusers to support abuse.

Is it though? Are our churches concerned about how their messages are received? Are our churches concerned about abuse survivors? Or are they more focused on so-called sound doctrine and on giving “grace” to abusers?