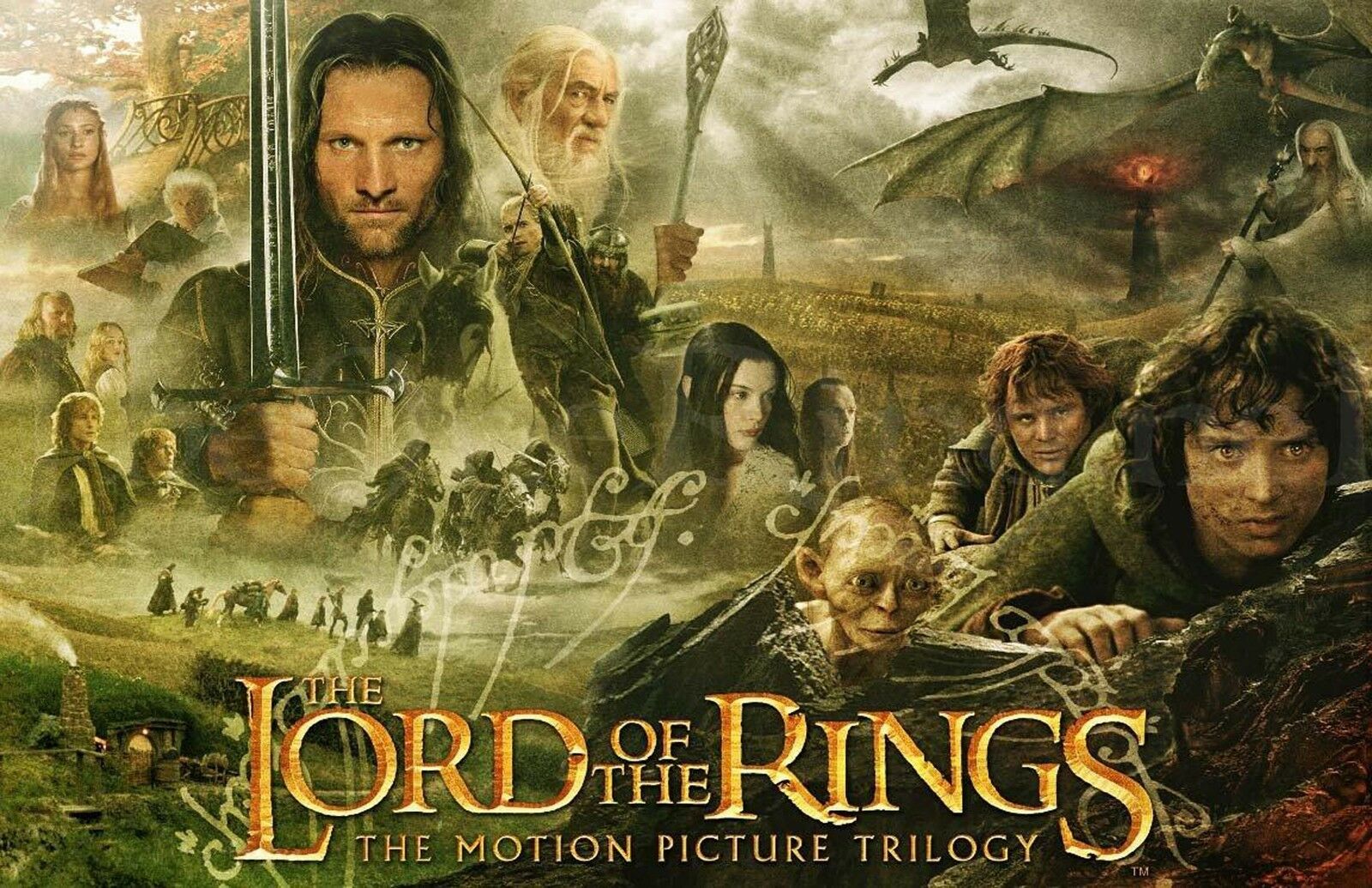

Review of The Lord of the Rings Trilogy, Directed by Peter Jackson

By PAUL D. MILLER

It is hard to remember how firmly entrenched the conventional wisdom was that The Lord of the Rings was unfilmable. A disastrous animated attempt in 1978, stuffed full of 70’s cheese, covered just half the story. The film only made $30 million, studio executives refused to fund the planned sequel, and a generation of children were condemned to confusion when the film ends and the ring has not been destroyed.

I remember reading a blurb in a magazine some 14 years ago confirming that someone was attempting a live-action trilogy of the entire book. I was mad, so convinced was I that the film would be poorly done and disrespectful of its source material. The high points of Hollywood’s few attempts at live-action big-budget epic fantasy before 2001 were Krull (1983), The Neverending Story (1984), Legend (1985), Labyrinth (1986), and Willow (1988). Those were the high points.

Like any fantasy geek, I actually liked most (okay, all) of those movies. But if that was Hollywood’s resume, would any rational adult believe it had the ability to adapt The Lord of the Rings? No. No one believed it could be done.

Peter Jackson proved the world wrong. The Lord of the Rings trilogy (2001-2003) earned $3 billion at the global box office, more than the original Star Wars trilogy. The films were nominated for 30 Oscars and won 19–more than the Godfather trilogy—including Best Picture, Director, Screenplay, Cinematography, and Visual Effects (three times). Contrary to popular belief, the acting was also recognized: Ian McKellen was nominated for acting in Fellowship of the Ring. All three movies are high on IMDB’s list of top movies (#13, 21, and 9, in order), and Fellowship of the Ring is #50 on the American Film Institute’s list of the greatest films of all time.

Few films achieve such complete success—commercial, popular, and critical—and are recognized in their own time as classics. Does The Lord of the Rings deserve its reputation?

Absolutely, yes, it does. But not for the reasons you might think. I suspect its ground-breaking special effects, which are truly a marvel and contributed heavily to the films’ success, may not hold up too well after another decade or so. In fact, they may not even look impressive compared to what we see in the upcoming Hobbit trilogy.

The truly impressive qualities of The Lord of the Rings, which will only gain lustre with age, are the trilogy’s fidelity to traditional themes (loyalty, friendship, and heroism), its surprisingly sophisticated psychology, and its evocation of powerful archetypal images.

For example, the key relationship across three movies is the friendship between Sam and Frodo. Sam’s loyalty to Frodo, and Frodo’s willingness to be seen in his weakness and to lean on his friend for help, is a powerful depiction of simple friendship. The hobbits’ courage—especially Merry and Pippin as they ride into battle—is another simple but powerful and timeless theme that grounds the films. Few movies evoke the virtues without including a snide subversion of them under the guise of irony. The Lord of the Rings is childlike in its guilelessness.

There is even genuine wisdom in the dialogue. Sam says at the end of The Two Towers: “There’s something good in this world, and it’s worth fighting for”—a decent one-line summary of just war theory. Earlier, in Fellowship of the Ring, Frodo talks with Gandalf:

Frodo: I wish none of this had happened.

Gandalf: So do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us.

This distinction between our circumstances and our responses to those circumstances is echoed in Paul David Tripp’s Instruments in the Redeemer’s Hands. As Christians, we understand that our circumstances are often filled with suffering and trial, but we nonetheless have a responsibility to choose to respond to them with patience and trust in God’s providential care.

The films also reflect a surprisingly deep and complex understanding of human nature. I know, I know: epics don’t focus on characters, and fantasy relies on archetypes. Gimli and Legolas aren’t exactly Hamlet.

But Gollum is. Gollum, the shrunken, hollow, sniveling wretch is among the great characters of literature. He is a tortured soul, a schizophrenic addict, a thing struggling against his own nature, conscious of his own looming damnation and unable to escape it. He is a heartbreaking portrayal of Romans 7:15-24 (alas, not verse 25).

Indeed, the object of Gollum’s idolatry—the titular Ring of Power—is a catalyst for sin for any characters who encounter it. Boromir and (initially) Faramir betray their promises, Gandalf and Galadriel become terrifying, and even Frodo becomes psychotic over the ring. It is the mechanism by which Tolkien introduces some depth and conflict into these fantasy characters.

The Lord of the Rings also paints some intensely powerful images. Whether or not Jungian archetypes really exist, Tolkien was apparently familiar with them and Peter Jackson found a way to project digital facsimiles directly onto the silver screen.

Gandalf’s dramatic return at the Battle of Helm’s Deep astride a white horse is the best artistic evocation of the Second Coming I’m aware of (Revelation 19:11). Note the music as he and the Rohirrim charge the field: it is a soft, redemptive, triumphant tune sung by an angelic choir, not the fast, heavy, tympanic track of an action scene. The point is not the swordplay, but the achievement of salvation.

It is not the only archetypical moment. The Shire is a warm, homey, comfortable place, with all the rustic comforts of a getaway to the countryside—a sort of permanent bed and breakfast where there is always a crackling fire and hot meal waiting for you. It is Home. The Gray Havens (Heaven); the Balrog (“a demon of the ancient world”); Sauron (Satan); Mordor (Hell); elves (angels); the Return of the King (the Return of the King)—Middle Earth is enchanted and peopled with images and ideas etched deep inside us. I could go on.

The Lord of the Rings gives opportunity after opportunity to see traces of the truth in it, which is reason enough to admire it. I have one more reason. The Return of the King came out in 2003. At the conclusion of the film, the four hobbits, having returned to the Shire, sit down at a pub. They look around uncomfortably: life has continued as normal during their absence. No one has any idea what the hobbits have been through, how close the world came to catastrophe, or what sacrifices they made. The hobbits look at each other knowingly: no one understands, and no one ever will, and you simply have to pick up your life and move on.

I am a veteran of the war in Afghanistan. Friends and family sometimes ask me to recount my experiences. I can recount facts, but I can’t make them understand. Jackson’s brief portrayal of returning veterans is wrenching, and cathartic, and true.