Okay, so I’m cheating a bit on this one for the sake of lining up the title with two other recent posts. (This one and this one,if you’re wondering.) Technically Abraham Kuyper’s life is pretty close chronologically to that of William Jennings Bryan, covered in an earlier review. And yet, Kuyper’s political life was focused on the first few years of the 20th century when Kuyper took office as Prime Minister of the Netherlands. So I stand by the title, even if Kuyper could also reasonably have been called as much a 19th century figure as a 20th century one.

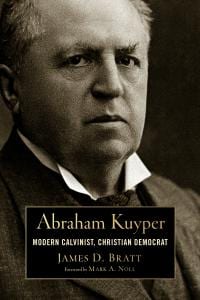

And, as should be clear, this is yet another post about Abraham Kuyper. Unlike the series of posts publishing on Tuesdays on this blog walking through Kuyper’s Common Grace, this post is about James Bratt’s biography of Kuyper, Abraham Kuyper: Modern Calvinist, Christian Democrat. Working on the leading edge of what has become a renaissance of Kuyper studies (and which I maintain should be called the ‘Dutch Renaissance‘), Bratt’s biography is engaging, thorough, and well worth your time.

I won’t attempt to do much summarizing, given how thorough this book is and how rich Kuyper’s life was. Instead, I’ll just mention three short reflections based on the book:

First, I’m very glad that Kuyper’s works are being translated. I hope that when they’re done with Kuyper they continue to work through 19th century Dutch Christian writings (some of the names like Prinsterer and da Costa really should also be more well known). For nearly a century English speakers (like me) have been restricted to the Lectures on Calvinism and a handful of devotional writings. And while these works are excellent, so are his more philosophical and political writings. Access to these can only be a blessing.

Second, Bratt does an excellent job highlighting Kuyper’s flaws. These come out in Kuyper’s writings as well, but here some of the unsettling racial comments and conclusions are faced head-on by Bratt. These should not be shuffled aside or explained away, but rather should be pulled into the light of the Gospel and dealt with in the wake of their historical impact (particularly in South Africa, where as Bratt points out Kuyper’s theology was twisted–but still used).

Finally, Kuyper should serve as a warning to contemporary American Christians who are over-invested in political victory. Abraham Kuyper is in the running for the most brilliant theologian of the 20th century (or 19th century, depending on where you want to place him), no one can doubt his Christian credentials. And yet, his religious footprint on the politics of the Netherlands is basically non-existent. I don’t know enough about Dutch history to know when their nation came to be identified with secularism and libertine-ism (though a couple of my Dutch friends tell me that like America, the Netherlands is a complex place with pockets of religious interest located mostly in the rural communities). So don’t look for electing a Christian President to save us.

All this to say, Kuyper’s life is well worth reading about, and this book is great way to start.

Dr. Coyle Neal is co-host of the City of Man Podcast and an Associate Professor of Political Science at Southwest Baptist University in Bolivar, MO