Tom McCall’s recent Forsaken: The Trinity and the Cross, and Why it Matters (IVP, 2012–thanks to IVP for a copy!) is a very stimulating little book. Its four short chapters (just 165 pages total) are a series of focused treatments of major issues in Christian faith. Tom McCall (associate professor of theology at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School) writes for the non-specialist in this book, and keeps things readable. But the intellectual skills he has displayed in his more academic writings (see especially the volume Which Trinity? Whose Monotheism? in which he fearlessly crosses the boundaries between philosophy, systematic theology, historical theology, and biblical studies) are also conspicuous here.

Here’s proof that Forsaken is stimulating: It stimulated two of the theologians at Biola’s Torrey Honors Institute to get together and discuss it. Fred Sanders and Matt Jenson have been meeting to talk through the book, and will share some notes from their conversations here.

In this post, Sanders and Jenson take up chapter 1, “Was the Trinity Broken? The Father, the Son, and Their Cross.”

Sanders: Now this is a chapter that needed to be written! Jesus’ cry of dereliction from the cross (“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”) is a profound and moving passage. But we hear a lot of strange things said about it these days: it is treated as “deeply troubling, revolutionary, unexpected, shattering,” and so on. It is all of that, but it’s high time to put up some boundaries about what conclusions can be drawn from it.

What I love about this chapter is that McCall makes two calls: first he calls for clarity on the meaning of these words, offering a whole range of possible meanings: that the Father rejected the Son? That the Father hid his face from the Son? That God cursed Jesus with damnation? That the eternal communion between the Father and the Son was ruptured on that fateful day? That the Trinity was broken? But when he gets to those latter statements, he makes his second call, which is to call shenanigans on the broken Trinity view. It’s either accidental nonsense, or a pernicious attempt to reject the classical Christian doctrine of God while continuing to use the traditional vocabulary. The former (accidental nonsense) is what we usually hear bits and pieces of at the popular level. The latter (rejection or at least revision of classical theism) is Mostly Moltmannian these days.

McCall affirms that “there is a genuine sense in which the Son in fact was abandoned by the Father.” To paraphrase Flannery O’Connor’s “You Can’t Be Any Poorer Than Dead,” it seems to me that You Can’t Be More Abandoned Than Crucified. But he also insists that “the Son’s relationship to the Father is unbroken,” and that “if we understand the doctrine of the Trinity properly, we will be in a position to see that saying ‘the Trinity is broken’ amounts to saying ‘God does not exist.’ Such a view is antithetical to the Christian faith” (p. 44). Just by exposing this error and giving it the label “The Broken Trinity View,” I think McCall has cleared the air. I can easily picture a preacher who is pushing his congregation to take the full measure of the atonement, going from one riveting statement to another, but (after reading McCall) knowing that he’d better stop short of Broken-Trinity-ism.

Jenson: But does it preach, Fred? I’m in extensive agreement with you, and equally glad for McCall’s confident correction of recent trinitarian speculation. And let’s call it what it is–speculation. Too often, the broken Trinity reading purports merely to be reading the passion narratives with eyes wide open. But a host of assumptions about what forsakenness must entail and what its implications for God must be end up being smuggled in between the lines. This is not a plain sense reading of the text, then, but a highly speculative venture. “What does this mean for God?” is always a dangerous question, and almost always doomed from the start. McCall puts such talk in its place and cordons off all God-talk as talk in which the eternal Trinity is always–even at the cross–the eternal Trinity, one God, world without end.

But I still wonder if it preaches. McCall’s economical writing may be to blame. Laser-sharp with his argument, he quickly surfaces the issue, identifies errors, corrects them and moves along. This chapter could have been a book by itself; it should have, in fact. In that book, he could have written a chapter or two on the depths of Jesus’ identification with broken sinners at the cross and on the agony he must have suffered in taking our place. It’s not that McCall misses these realities; he nods to them at points, and hints at the depth of consolation one might draw from meditating on the death of Jesus as a revelation of the Father’s love for his Son and their love for the world.

The strength of the broken Trinity thesis is its pathos. I remember praying with some friends for someone in deep pain after first reading Moltmann’s The Crucified God. I was moved by the compassion of a God who would be in such awesome solidarity with those who suffer and spurred to pray with renewed zeal. Along with McCall’s theological correction, we need to hear more about how the unbroken Trinity is present to and for sinners at the cross. And we need to hear in this an affirmation of (1) the triune God’s perfect, loving unity in (2) his radically self-giving gift which entails (3) the eternal Son’s profound suffering in the flesh for us and our salvation. If we only have (1) and not (2) and (3), we end up in a triumphalism foreign to the victory of the cross. If (3) doesn’t entail strife between Father and Son, it still entails deeper suffering than I have ever known–possibly deeper suffering than anyone has ever known.

Sanders: Ditto on wishing McCall had spent more pages dwelling on a few of the points as he built up his case. For example, he gives a quick survey of the history of interpretation of the cry of dereliction, just enough to show that there’s a classical Christian consensus approach to it and then draw the contrast to the radical Trinity-breaking of recent theologians. It made me wish for a more expansive survey of the history of interpretation of this doctrinal nexus: Not just the cry itself, but also two Pauline passages that always (to my surprise) seem to impinge its interpretation: 2 Cor 5:21 and Gal 3:13. Graduate students looking for a topic, take note.

But I don’t intend this as a critique. I think McCall provided just enough detail to get the job done, and the job is to reject an overly-drastic reading of the cry of dereliction and replace it with a better one. Does he in fact provide a preachable option? I think so.

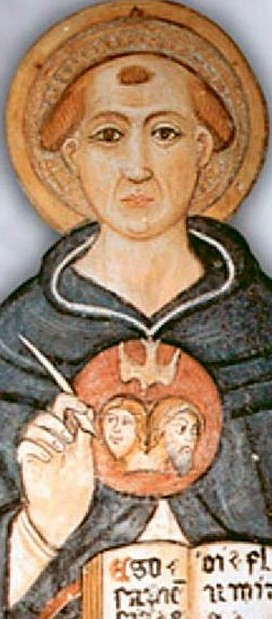

Let me try to make the argument by way of illustration. In the history of art, there is one particular way of presenting the doctrine of the Trinity, called the “Throne of Grace Trinity.” It takes the image of the crucifixion and superimposes it on an image of God the Father seated on his throne. The dove of the Holy Spirit is located between the Father and the Son (usually descending, but sometimes ascending). Here is one of my favorite versions of the image, a fifteenth-century sculpture from the collection of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco:

For all that’s wrong with this image (God as old man, gigantic dove over tiny cross, etc.), by juxtaposing two main scenes it makes one point very well: That the Christian message tells of Christ crucified and God on the throne. Not just Christ crucified, which might be merely another martyrdom if you left out the divine intention behind it. And not just God on his throne, which runs the risk of aloofness and unconcern. Neither of those would be good news in isolation. But this statue combines them. It’s practically Romans 3:25 in visual form: God putting forth Christ as a propitiation.

Supposedly the imperturbable “God of classical theism” runs the risk of being aloof. Moltmann and other modern theopaschites compensated by putting God, all of God, the divine nature itself, on the cross. I know their intentions are good, but the result is a suffering God who seems too busy feeling his own pain to feel ours. To get the message right, we need to confess a God who cares deeply, takes action, and yet remains entirely blessed in himself (especially as the Trinity).

Jenson: Amen to that! Somewhere along the way, proponents of a broken Trinity seem to forget that “God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son.” And the Son, who only does what he sees his Father doing, freely gives himself. He is not a hapless victim, but the great high Priest who willingly sacrifices offers himself as a sacrifice for the sins of the world. “For this reason the Father loves me, because I lay down my life that I may take it up again. No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord. I have authority to lay it down, and I have authority to take it up again. This charge I have received from my Father.” (John 10:17-18) Notice the back-and-forth of Jesus’ rhetoric–it’s my life to do with as I will, and I will to lay it down, which is the Father’s will. It seems the only one whose will impinges on the incarnate Son is the Father, and yet the Son’s will is perfectly aligned with the Father’s so that this is perfect autonomy–that is, trinitarian autonomy.

With this in mind, I wonder whether the Throne of Grace Trinity above doesn’t reference a third scene–Jesus’ baptism in the Jordan. At one point, he calls his impending death a baptism (Luke 12:50). Might the crucifixion, where Jesus commends his spirit to God (the dove ascending?), be the scene of the Father’s greatest pleasure in his beloved Son, anticipated at the Jordan in the dove’s descent? Finally, we get to pneumatology, which is the final nail in the coffin (pardon the awkward metaphor) of the broken Trinity hypothesis. The same Spirit who signals the Father’s delight in his Son drives the Son into the wilderness to be tempted, anoints him for ministry and sustains him through death. The life-giving Spirit vindicates him in the resurrection, a further sign of the Father’s love.