Every so often, some ill-informed person opines that we don’t need Black History Month, or International Women’s Day, or LGBT History Month, or the BET Awards. Sure, we wouldn’t need any of them if white privilege, male privilege, and straight privilege didn’t exist. But they do exist.

People who argue that Black history has been “relegated” to Black History Month are missing the point. Prior to the creation of a special month, Black History was completely ignored, except as a footnote to white history. The month is an attempt to get a foot in the door – a door that was previously slammed in the face of Black history.

If “mainstream” history didn’t focus almost exclusively on straight white men, then we wouldn’t need days or months that focused on the people who are usually left out of the history books. But only recently, a British student launched a petition to persuade an exam board in the UK to feature female composers on the GCSE music syllabus. The petition was successful, but she shouldn’t have needed to create a petition: it should have been obvious that female composers should be included.

A great deal of art, music, and literature has been produced by women, Black people, and LGBT people, yet school, college, and university syllabuses frequently focus exclusively on art, music, and literature produced by straight white men. It is not that the artistic productions of straight white men are superior to those produced by Black people, women, and LGBT people – it is because the straight white male view of the world is deemed normal and normative, and anything that doesn’t fit within it is deemed niche or uninteresting.

It is time for the marginalised to be restored to the historical account. Black people have been denied a history, and erased from history. David Olusoga writes:

No other people see history in quite the same way because no other people have had their history so comprehensively denied and disavowed. Among the many justifications for slavery, and later for the colonisation of Africa, was the assertion that Africans were a people without a history. The German philosopher Hegel, writing in the 1830s, claimed that: “Africa … is no historical part of the world.” Other peoples have seen their cultures dismissed as backward or barbarous, but the antiquity of those cultures has rarely been so repudiated.

The erasure of African history and culture is similar to the erasure of the stories of the pagan cultures of antiquity. Only cultures that built in stone and used writing were deemed worthy of the lofty title of ‘civilisation’. Only cultures that were Christian were deemed civilised – everyone else was just barbarian hordes.

So, until the educational syllabuses are reformed root and branch, there will continue to be a vicious cycle of the straight white male view being presented as normative, and the situation will be perpetuated from generation to generation. Ideally, so-called minority history should be integrated throughout the syllabus and presented in context, but until that happens, we still need a special focus. As Andrea Stuart writes (in response to David Cameron claiming the British abolition of slavery as a triumph, despite the fact that Britain started the Transatlantic slave trade), Black History Month can only be declared a success once it’s redundant

:

So why does this ignorance persist, 25 years after Black History Month was launched in Britain? This month we’ve seen events that range from the sublime, such as the award-winning American musical The Scottsboro Boys, to the tokenistic. At my children’s school, many heart-warming pictures of Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu and Doreen Lawrence have been produced, as well as innumerable portraits of black sportsmen from Usain Bolt to Theo Walcott. At a friend’s school, the pupils have been encouraged to turn up dressed as a black pop star. Most of our children have become familiar with the travails of Mary Seacole. But these stories of individual triumph, however uplifting, don’t do nearly enough to fill the knowledge gap. We need to integrate black history across the educational curriculum, and among adults, so that people like our prime minister will also comprehend it.

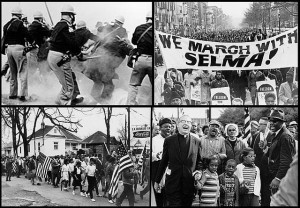

It also perpetuates the lie that Black people, women, and LGBT people didn’t do anything much in history. And it promotes the idea that change happens when those in power graciously decide to give rights to the oppressed. Whereas the truth is that every single right we possess was wrested out of the hands of the powerful as a result of a protracted struggle by the oppressed. Black History tends to focus on safe and sanitised Black heroes, rather than the lives of ordinary people, or of revolutionaries like Toussaint L’Ouverture. These heroes are presented out of context, writes David Olusoga:

There’s no doubt that black British history, as celebrated during Black History Month, has helped thousands of black children understand their place within the British story. Each year it provides journalists and broadcasters with a topical hook on which to hang stories about black people and black history that might otherwise go untold. And the stories of remarkable men and women – from Britain and around the world – become counterweights against the tsunami of negative stereotypes that wash over black children growing up in this country. But the problem is that biography, especially heroic biography, can at times displace and obscure history rather than explain or deepen it. This is because the life stories of the men and women who make up the pantheon of black heroes are not wide enough, even when viewed together, to encompass the global scale and variety of black history.

The promotion of history as the story of straight white men erases and denies the oppression suffered by Black people, LGBT people, and women, and erases and denies their struggles to overcome that oppression.

That is why I support Black History Month, and especially Crystal Blanton’s Thirty Day Real Black History Challenge. It is why I support LGBT History Month and International Women’s Day and Women’s History Month.

Black History Month is in November in the UK, and in February in the USA and Canada.

LGBT History Month is in February in the UK, and in October in the USA.

Women’s History Month is celebrated during March in the USA, the UK, and Australia, to include International Women’s Day on 8 March, and during October in Canada.