So, the Synod.

I remember, at the height of the kerfuffle about dissident priests being “silenced” in Ireland, wondering if it wouldn’t be better if Bishops just took this as an opportunity to teach the faith. If instead of having less talk, we had more?

That’s what just happened. Debate. Discussion. Dialogue. I wanted it, I got it.

And, overall, I’m pretty pleased. I think Austin Ivereigh has the right take: the Church has nothing to fear from robust dialogue.

This kind of debate is the sort that the Church needs in order to thrive. A creative tension between those seeking development and those seeking to safeguard the truth. Maybe there are some Bishops who are trying to sneakily undermine Church teaching. But I’ve seen no evidence that there are many. What we have is a group of people sincerely trying to guide the church towards doing the right things in the right ways in the area of pastoral care. And the process itself (after overcoming some hurdles) ended up as perhaps the most open, transparent discussion the Vatican has ever held. It remains to be seen what the final result will be. But I am hopeful.

The thing is, the Synod can talk all day and all night, and perhaps at the end it will come out with an utterly fantastic document. But, absent practical implementation, these will be empty words. The Church needs to ensure that its message becomes lived reality: and for that we need spiritual direction.

I wrote a few sentences ago that the Church has nothing to fear from open dialogue, but that’s not quite right. It has to fear the prospect of a warped, flattened, simplified, vulgarised version of its message reaching people – the mainstream media version of Catholicism.

Often, this danger is cited as a reason not to err too far on the side of mercy – to give the media (and, let’s be honest, more than a few theologians) ammunition to preach a milquetoast Catholicism that shies away from leading people deeper into the bright burning heart of the Church: true relationship with Christ.

But this danger of misinterpretation applies just as equally to more rigorous pronouncements.

I really liked the mid-term relatio’s language about gay people, the language that freaked a lot of people out.

“Homosexuals have gifts and qualities to offer to the Christian community: are we capable of welcoming these people, guaranteeing to them a fraternal space in our communities? Often they wish to encounter a Church that offers them a welcoming home. Are our communities capable of providing that, accepting and valuing their sexual orientation, without compromising Catholic doctrine on the family and matrimony?”

I’d share some of Eve Tushnet’s quibbles about the precise meaning of “sexual orientation”, but overall the language was warm, and real, and felt more like true welcome than any other document that Rome has released on the subject. I’m sorry that there wasn’t anything like this in the final document, and I hope that something similar gets put back in. To those who ask “why single out gay people? Doesn’t everyone have ‘gifts and qualities’ to offer? Why was this needed?” I would reply with another question: don’t Christians have quite a lot of catching up to do when it comes to treating gay people with love and charity?

I, for one, am not secretly agitating for change in the Church’s teaching. I’m the guy who goes out on TV and radio and campaigns against gay marriage (though I favour civil unions). I think children deserve the love of a mother and father where possible, and I accept the Church’s teaching on sex. But gay people are our brothers and sisters, many of them are trying to follow Church teaching and getting little to no support, and all of them are to be welcomed into the Church of Christ with open arms.

Yeah, this kind of language can be misinterpreted, and yeah, it was. A lot. I did die a little inside when the Irish Times’ editorial page came out with this gem:

Politicians under pressure from conservative lobbies can now rely securely on a defence that at least some bishops are sympathetic to changes in our laws on, for example, divorce or same-sex marriage. Catholic teaching may not change, but doctrine can develop, Catholic practice is changing, and there are now two Catholic views that can claim authenticity.

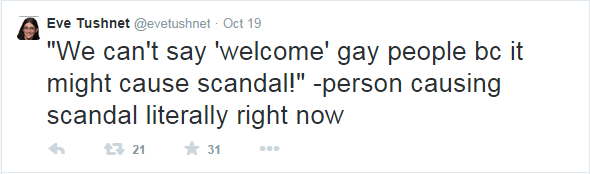

But anyone who thinks that the Church’s previous tone on gay people wasn’t misinterpreted just as disastrously is kidding themselves. Eve Tushnet again (buy her book):

Or consider the other hot-button issue of the Synod, one on which I hope the Church does not change its practice: Communion for the divorced and remarried. If the Church, after a full, frank and open discussion, decides against change, this will absolutely be spun into a rejection of divorced and remarried people, a retrograde step, a great opportunity missed, the triumph of Dark Forces(TM). Of course it will. That’s how this works.

The problem is not the language. The problem is the messing. And the only way to avoid that is to talk past the media. Talk directly to Catholics in the pews. How? Spiritual direction.

One thing that struck me about a lot of the best writing I have read in defense of the gradualist approach taken by the mid-term document involved spiritual direction. Calah Alexander’s powerful account of coming to full communion with the Church in the most difficult of circumstances only had the happy ending it did because she and her husband had a priest as a spiritual director, someone who knew them and their case and was able to apply the Church’s teaching with both fidelity and real mercy.

Sarah of A Queer Calling wrote a great open letter to Cardinal Raymond Burke, taking him to task for saying that gay couples shouldn’t be welcome at family gatherings. If you read Lindsey and Sarah blog about being a celibate couple in a denomination with a traditional sexual ethic, you’ll find the importance of spiritual direction cropping up all over the place. It’s how you both welcome people and challenge them – not through parishioners engaging in busybody snooping into LGBT people’s sex lives (seriously, go and look at Lindsey and Sarah’s Twitter feed at the moment. It’s instructive. And appalling). A proper spiritual director can do what the most welcoming Synod document, the most orthodox, brilliant homily, can never do: meet people where they are, and lead them to where they need to be.

The thing is, that kind of experience just isn’t happening that often.

Pastoral sensitivity requires pastors. You give them spiritual direction. And it’s just an unfortunate fact that most Catholics in the pews don’t have the kind of relationship with their parish priest that is necessary for spiritual direction or proper pastoring to happen. They don’t have that relationship with any priest.

So go to your priest and ask for spiritual direction. If they’re unequipped to give it, they need to be trained. How about the Bishops returning from the Synod organise some training? Get the most holy, orthodox, pastoral, badass spiritual directors in each country together and get them to give a few workshops.

And why stop with priests? In my own neck of the woods, Archbishop Diarmuid Martin has been making moves recently to involve lay people in the running of the Dublin Archdiocese. Why not mobilise a small army of lay spiritual directors? Train up a whole bunch of married couples, single people, straight people, gay people; people who know Christ, and love His Church. Teach them so that they might teach others.

This is kind of important. Without spiritual direction, the Church in the West is in very, very big trouble. Because, whisper it, it’s actually impossible to lead people into authentic Catholicism just via homilies and public statements. You’re always going to fall into either rigorism or laxism: you’re always going to end up either laying too heavy a yoke on some people’s shoulders or offering “cheap grace” to others.

Spiritual direction is essential. It’s where the rubber meets the road, where the hard, complicated work of applying Church teaching to individual circumstance should be happening – where it needs to happen.

Synods will come, and synods will go. I have hopes for this one: I hope the Church doesn’t undermine its teaching on the indissolubility of marriage through misplaced mercy, I hope that we get some coherent strategies for ministering to people in non-traditional families, and I hope that those who want to see doctrinal change aren’t too disappointed when the debate reaches its conclusion and we’re still left with (surprise!) Catholicism.

But without spiritual direction and authentic pastoral care to put it into practice, anything this Synod or any other brings to the life of the Church will be lost, like tears in rain.