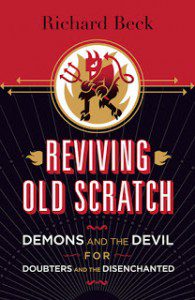

In his new book, Reviving Old Scratch: Demons and the Devil for Doubters and the Disenchanted, psychologist and professor Richard Beck describes a personal encounter with the devil:

In his new book, Reviving Old Scratch: Demons and the Devil for Doubters and the Disenchanted, psychologist and professor Richard Beck describes a personal encounter with the devil:

“I didn’t smell brimstone or see a horned shadow on the floor. But I do recall, in a way that haunts me to this day, love crashing into a wall…I’d run into something. And that something knocked me off my spiritual feet.”

Beck had been leading Bible study in a prison, but when he tried to preach on the Beatitudes and the blessedness of the meek, he’d been told “you can’t do that stuff in here.” You can’t preach meekness as the path of blessedness to inmates. In prison, meekness is weakness, and weakness will get you killed.

“Who was I to insist that these men become ‘weak’ in such a dangerous place?” he writes. This was the night Richard Beck started believing in the reality of the devil and his minions–“forces adversarial to meekness, to all the Beatitudes, making the Way of Jesus risky, costly, and even dangerous.” Prison isn’t the only place that meekness is dangerous. It’s the way of the cross.

Beck argues for the existence of an actual, literal Satan–an evil spirit out for souls–mostly to the liberal Christian intelligentsia who make up his readership. These are the “disenchanted” of his subtitle–Christians who have have mostly done away with the supernatural dimensions of Christianity, who shy away from terminology like “spiritual warfare” because those words sound old-fashioned and superstitious and have been wielded as a weapon against the wrong people for too long. I hated the vocabulary too, after growing up for a time in a fundamentalist Christian home where I was perceived to be in the hands of the horned guy with the pitchfork rather than suffering from natural and even holy grief for my dead mother.

I believe in the devil, but I dismissed the whole idea of “spiritual warfare” as a way for fundamentalist Christians to demonize the other–those who don’t share their beliefs–and to deny their own capacity for evil, and Beck agrees that it has been deployed in such ways. But not just by fundamentalists who fear their “rebellious” children are demon-possessed. Liberal and progressive Christians, he says, are just as guilty of giving evil a human face and and using it as an excuse to vilify their neighbors–but they tend to do so in the name of “social justice.” They limit evil to a social and political realm. The problem with that sort of thinking is that, just like their conservative counterparts, liberals ultimately demonize those who don’t agree. In what he calls the “Scooby Dooification” of evil, there’s always a human behind the curtain, causing all the problems, which means we can eradicate it by changing the minds and actions of wrong-headed humans. For the “disenchanted” Christian, there is no supernatural explanation, there’s just bad politics. But Beck thinks that Christianity without the supernatural is not Christianity at all. Until we recognize that we’re all living in a spiritual war zone, we’ll underestimate evil and the power we have to fight it.

That’s why I love Beck’s description of love crashing into a wall. I’ve felt it–an almost physical force–and maybe you have too, at a moment in your life when love just didn’t win. Stillbirth. Illness. Betrayal or abandonment by one who was supposed to love and protect you. Suddenly, evil gets personal. I think this is why deep personal grief so often feels like fear. Because even if a mass shooting breaks our hearts, unless it’s your child in the classroom or in the gay club, your husband in the tower, we’ll usually find a human face, or a whole group of them, to blame. “Spiritual warfare isn’t just about a political struggle with the principalities and powers,” writes Beck, and he offers a list of scriptures that describe our struggle with the devil as personal. And I’d say, yes, when it gets personal, it’s easier to believe in the existence of supernatural evil–a force that is totally inhuman, that distorts and resists and even hates love. A force that wants to destroy what is good. A force that doesn’t fight fair and strikes at the weakest spot.

That’s why the counterforce, according to Beck, is not human love. Or it’s not merely human love. Human love is too easily distorted by evil. That’s the devil’s favorite trick. Take away the object of my love–swiftly and cruelly–and see what happens. Often it’s despair and a loss of faith. (And as we learned in The Exorcist, the devil wants us to despair.) No, the counterforce to evil, Beck thinks (and he credits the Catholic tradition here, on page 128) is that other unpopular Christian word: Holiness. His thoughts on the recovery of desire for holiness are some of the most interesting in the book.

If few of us believe in the devil, even fewer would desire to strive for holiness. That would be embarrassing, because we equate holiness with puritanical piety, when really, Beck argues, it “is the discipline needed to protect our love in a world that is satanically antagonistic to love.”

Beck doesn’t really concern himself with why God allows the devil to exist. He dispenses with theodicy in an early chapter, resigning himself to the fact that evil is real and we need to mount a resistance instead of spending all our lives wondering why: “A theology of revolt trades in philosophical bafflement for boots on the ground.”

“Pat Benatar got it right,” he writes. “Love is a battlefield.” It’s where God is at war, Beck says, and it’s time to get off our theological asses and get in the game.