In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes speaks of the photograph’s punctum, of the detail that punctures, that draws the attention of the individual viewer and provokes an emotional response based on personal associations. There’s a photograph of me as a baby, wearing something soft and white, including a soft, white hat with a huge pom-pom. I’m being held by Peter, my erstwhile father (who I haven’t seen in years). I believe we’re standing on a porch, and in this black and white photograph, the porch looks pleasant enough, much more pleasant than it looked on a recent visit to our hometown, when my mother pointed out our first residence to me. Maybe the porch in the photograph is a different one, or maybe time has given this house its neglected air. Even back then, it would have been in one of the town’s less desirable areas. The photo is slightly blurred—Peter was normally the one who took the pictures, as it is his camera. The white of his shirt and the white of my outfit are slightly blown out, a bright blur of humanity. But I am looking at the person behind the camera. I am a baby. I am happy enough. Peter, on the other hand, looks uncomfortable, his head slightly back to see above my pom-pom, his eyes apprehensive. Punctum.

*

I recently watched a series of videos in which Annie Leibovitz discussed photographs and how to take them. Each video ended with an assignment. One was something like, Take a photograph of an older person you know. First ask if they have a picture from when they were younger. How does it inform the photograph you take? With my mother, I visit my grandmother for her 90th birthday and I decide to recreate a photograph I’ve just run across on Facebook. It is the 1950s. My grandmother is holding my mother, who is a baby. My mother looks like she has just been studying the world and my grandmother has been studying her studying it. Gran once told me that my mother showed remarkable alertness and interest in the world from the time she was an infant, that she would hold the baby up to the window so she could study birds, and that she could tell there was something unusual about her, something brilliant. On our visit, I have them stand in the yard and look in the same direction. I ask my grandmother when she first knew my mother was a genius. “Oh, I always knew,” she answers. I take the picture.

*

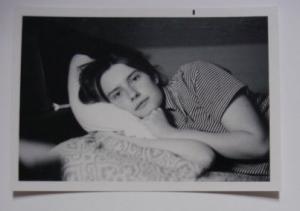

A year after 9/11, I left Philadelphia, where I was getting a doctorate, and moved to Minneapolis, where my mother was living. I began dating a photographer-turned-carpenter, and I later acquired from him one of his old 35mm film cameras, on which I began to learn to shoot black and white photos. When I returned to Philadelphia to defend my dissertation, I practiced on my friend Dennis, who I briefly dated the summer before I moved away. After I got to Minnesota, I would sometimes call Dennis for pep talks. In one, he remarked that I was always nicer to other people than I was to myself. I never forgot that. I can see something of this quality in Dennis’s relaxed face in a photograph I took of him on that visit—a good-humored interest. An interest in seeing and being seen. Kind regard. Punctum.

*

Throughout my 20s and most of my 30s, I had a gray cat named Andy Garcia. Andy was half-feral, and I had named him after the crazy look that Andy Garcia has in his eyes in The Godfather Part III. He was crazy, but he was my friend. The only time he was ever consistently docile was toward the end of his life when he was very sick. A friend who had known him years before visited my house at that time and remarked on his gentleness. We both knew he wasn’t long for this world, and in fact he died that week. I have a photograph in which I’m leaning down to place my head close to Andy’s, and the punctum for me in that one is that my eyes look very bright and very blue, but I know they look that way because I’ve just been crying.

*

Another of the Leibovitz assignments is to think about the photographs that were around during your childhood and how they may have influenced you. For her, it’s a photograph of her mother’s family taken by an anonymous boardwalk photographer. Everyone is lined up in a row from youngest to oldest, flanked by the parents. They are in a simple group, but each person is present in him- or herself. For me, the influential photographs were the ones Peter took of me as a baby and of my young mother. In many of these portraits—which my mother collected in a large red photo album—she looks sad. She is only 19 or 20. She will return to college. She will see other sights. But for now, she is in a room with a baby. She is resting on a bed, while the baby sits and looks out a window. Mother looks tired, baby alert. When I was a young child, she made me feel seen, my mother. And in these photographs, at least through his camera, Peter sees her.

Joanna Penn Cooper curates the “Approaching Mystery” series for Sick Pilgrim, publishing flash essays by writers encountering the unseen, the uncanny, and the unresolvable. The photograph above is her mother.

Do you feel like writing about a portrait? Here’s an assignment: Take a picture of someone you know and like, a portrait. (Or look at a portrait you already have.) Now also write their portrait in one to four paragraphs. The portrait that you write is the punctum. You can find an example on Joanna’s blog.

Joanna will be teaching an online flash essay course starting Friday March 16th. More information can be found here: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/approaching-mystery-an-online-flash-memoir-course-tickets-42572637906