Our reading this week is from the gospel of Luke:

Now all the tax collectors and sinners were coming near to listen to him. And the Pharisees and the scribes were grumbling and saying, “This fellow welcomes sinners and eats with them.”

Welcome Readers! Please subscribe to Social Jesus Here.

This is Part 1 of Sheep, Coins, and a Preferential Option for the Marginalized

So he told them this parable: “Which one of you, having a hundred sheep and losing one of them, does not leave the ninety-nine in the wilderness and go after the one that is lost until he finds it? When he has found it, he lays it on his shoulders and rejoices. And when he comes home, he calls together his friends and neighbors, saying to them, ‘Rejoice with me, for I have found my sheep that was lost.’ Just so, I tell you, there will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who need no repentance. Or what woman having ten silver coins, if she loses one of them, does not light a lamp, sweep the house, and search carefully until she finds it? When she has found it, she calls together her friends and neighbors, saying, ‘Rejoice with me, for I have found the coin that I had lost.’ Just so, I tell you, there is joy in the presence of the angels of God over one sinner who repents. (Luke 15:1-10)

The imagery in the first part of our reading this week is found in both the canonical gospel of Matthew and the non-canonical gospel of Thomas. The lost coin image is unique to Luke.

In Matthew’s gospel we read:

If a shepherd has a hundred sheep, and one of them has gone astray, does he not leave the ninety-nine on the mountains and go in search of the one that went astray? And if he finds it, truly I tell you, he rejoices over it more than over the ninety-nine that never went astray. So it is not the will of your Father in heaven that one of these little ones should be lost. (Matthew 18:12-14)

In Thomas, we find a little different flavor:

Jesus said, “The kingdom can be compared to a shepherd who had a hundred sheep. The largest one strayed. He left the ninety-nine and looked for that one until he found it. Having gone through the trouble, he said to the sheep: ‘I love you more than the ninety-nine.’” (Gospel of Thomas 107:1-3)

In Matthew’s gospel, this imagery answers the question “Who is the greatest” in the kingdom of heaven. Matthew’s Jesus centers one of the most vulnerable and marginalized populations in his society, children, and then tells the story of a lost sheep.

In Luke’s gospel, Jesus tells a slightly different story. Luke uses this story to justify Jesus’ fellowship with those whom the powerful, propertied, and privileged felt were inferior: tax collectors and others labelled sinners.

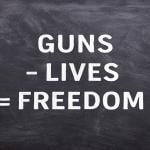

The term “sinner” is used quite differently in the gospel stories than in Paul’s epistles. I grew up in a very Pauline-flavored expression of the Christian faith. It was drilled into me that we are all, without exception, sinners. But in the gospels, the term “sinner” is not universal but used by those in positions of power and privilege to define someone else as living outside their interpretations of Torah, as outside of the covenantal community’s moral expectations, or simply as their moral inferior. In certain cases, the person was simply someone who disagreed with how Torah was being interpreted in a specific situation. The term was used to label, define and then marginalize others. In many cases, innocent people were being labelled as sinners while those in power, who were exploiting the poor and marginalized and were therefore the real sinners in the story, were deemed righteous, holy, or morally superior.

Using religion and claims of moral superiority to exclude people is, I believe, a misuse of both religious beliefs and ethical principles. At its core, most religions teach compassion, humility, and acceptance, yet individuals and institutions sometimes distort these teachings to justify exclusion. Just like in our story this week, by positioning oneself as morally superior, people succeed in creating an “us vs. them” dynamic, labeling others as sinful, impure, or unworthy. This approach fosters judgment and exclusion rather than an openness to understanding and perceiving our world from different perspectives. It fosters a conformity aligned with power. It then enables discrimination under the guise of righteousness. Such behavior can lead to the marginalization of those who are different, whether those differences are due to race, sexuality, gender, or a difference of belief, all while absolving the perpetrators of responsibility. In fact, it often makes the perpetrators look more holy because they are mistaken as standing up for morality. Ultimately, using religion as a tool for exclusion betrays the inclusive and compassionate values many faiths promote. True moral strength lies in empathy, not in self-righteous condemnation or the gatekeeping of worthiness based on personal biases or prejudices cloaked in religious justification.

In context, the lost sheep story takes on new meaning. We’ll begin here, in Part 2.

Are you receiving all of RHM’s free resources each week?

Begin each day being inspired toward love, compassion, justice and action. Free.

Sign up at HERE.