Last week we talked about suicide and abuse. Now, for a moment, let’s turn our attention on how we, as people who are not clinicians, can help people who have been abused. I take it as fundamental that in an emergency you should call paramedics, and that people who are suicidal shouldn’t be left alone with knives or belts, and that it’s highly abusive to call 911 or use force on someone who isn’t actively suicidal but just expresses a desire for death.

But what else can we do, as ordinary people who want to help? Just recently I’ve met a shocking number of people who honestly believe that you shouldn’t be gentle with a person who is suicidal. You ought to be stern and remind them that it’s a sin, that they’re wrong to desire suicide, that they’re selfish, that they’ll go to Hell and rot there, or else you’re making them more likely to kill themselves. And this is a very strange belief, to me. Who can say that they’ve ever been spurred to good behavior by bullying and nastiness? Bullying is abuse, and abuse doesn’t make you a good person. Conversion comes from seeing the good, and that you’re capable of good. Contrition comes in seeing that you could have done good, but turned away. To know you’re capable of good, you have to know you’re good. And I don’t know how to teach a person that they’re good except to love them, and help them to feel loved. Love is the only proper response to a good thing. To not love is sacrilege.

How do we love people? Especially wounded people, people who have been abused and don’t feel loved– even people that want to die?

Well, here’s one way that I’ve found. Remember when I talked about gaze, and the proper way to look at people? I said that a person is a kind of icon. I am not an iconographer, but I’d like to be; I love to paint and I love to look at icons. I came to my art class one day, when I was assigned to paint a “narrative image,” and asked if I could paint a painting based on an icon. The professor was excited. “Yes,” he said. “Icons are very narrative! Every icon tells a story.”

And of course, he was right. When you learn about iconography, you learn the stories icons tell; how this or that gesture has meaning, how different moments in the same narrative are portrayed on the same icon all at once, and how to know what story is being told. Every icon tells a story. Every person is an icon. And, in my experience, every person has a story. Abused and suicidal people have stories, too: horror stories. They have stories that caregivers have refused to believe; they have stories that they themselves can barely believe because they’ve been disbelieved so many times. And what they long for most, is for someone to listen and believe them.

When I was very, very ill after having been raped, a friend came to visit me. This friend happens to be a psychiatrist. He knew this wasn’t the first time I’d been abused; he saw that I was out of my mind with trauma. I admitted I’d been standing by the cliff again, wishing I could die. He probably could have called the police on me and had me taken to a hospital, but he didn’t. Instead, he listened. He listened to what happened. He didn’t speak much; he made sympathetic noises from time to time, and he told me that it was normal to feel the way that I did after all that happened. He said it would be a definite sign that something was wrong with me if I didn’t want to die. But other than that, he listened. As he got up to leave, I offered to hug him, and he hugged me back. And I didn’t die.

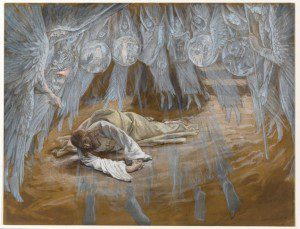

Listening is an essential part of the proper gaze; listening is part of the reverence due to an icon. Listening attentively to fellow human beings is a part of our duty as Christians. Every human we encounter is not just an icon, but a little christ. The story of this christ and what he has endured, is a little gospel and a little passion narrative. This is a christ on earth who may have experienced the abandonment of the agony, but who has not yet tasted resurrection. We know so little about the life of Christ, and most of His years on earth are shrouded in mystery. We know even less about the little christs who live among us; it’s a sacred gift to be able to hear their stories, if they want to tell them. Always listen with loving attention. Empathize. You are not a different kind of icon than they. God doesn’t love you any more or less than He loves them. What happened to them could have happened to you, and someday, perhaps, it may happen to you. Don’t ever tell them they shouldn’t talk to you but only to a therapist. The therapist may be able to help in ways that you can’t, but you don’t need training to listen. Anyone can listen. What was done to them was obscenity and sacrilege, but speaking about it is only telling the truth. Truth should never be suppressed. Let them speak to you. Listen.

Listen and empathize, and don’t be quick to tell them that how they feel is wrong. Don’t be quick to tell them anything, except that they are loved, and do that by listening. Believe them, and say so. If you can’t imagine the pain, tell them that, but believe them. Don’t follow up with advice unless they ask for advice. Don’t be harsh unless there’s no other choice– and there’s almost always another choice. People need to have their stories heard as much as they need food or shelter; you shelter and feed their souls, when you listen.

Listening to icons is not all that’s required of Christians, but it is required. Listen to the little gospel, and believe.

(image: “The Grotto of the Agony” by James Tissot, via Wikimedia Commons.)