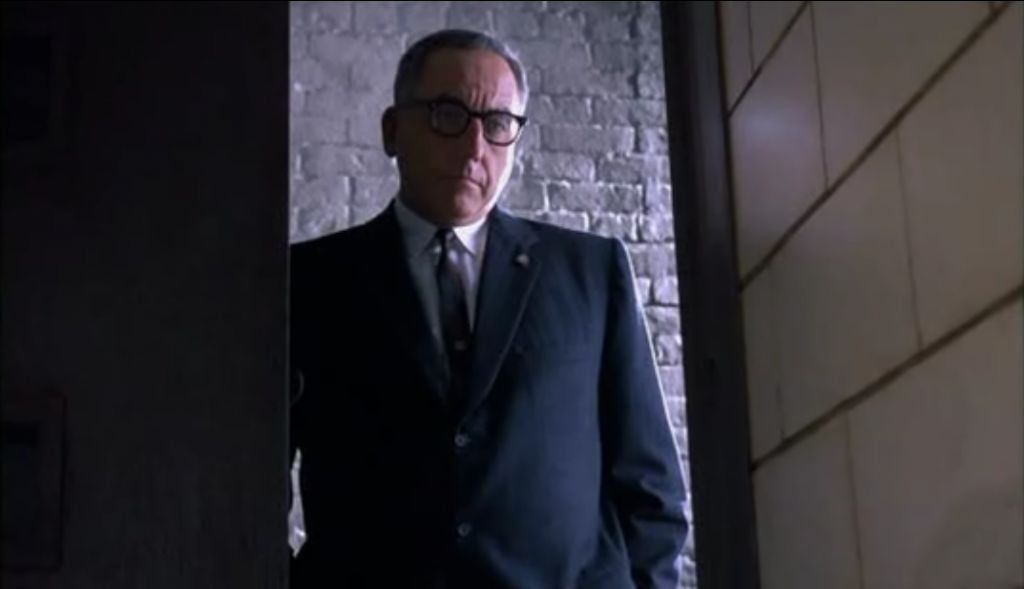

It’s a somewhat dispiriting notion for the religious viewer that the most explicitly religious references within a film like The Shawshank Redemption come from the bad guy.

On Andy’s first night in Shawshank, he tells the new inmates, “I believe in two things: discipline and the Bible. Here you’ll receive both. Put your trust in the Lord; your a** belongs to me.”

But despite Norton invoking God’s authority, his intentions are far from holy. Not only does he launder money for his own gain, but he maintains his iron grip over the prisoners at Shawshank through fear and violence. This is most explicit when Norton arranges the death of Tommy after he tries to help Andy get his fair trial.

Norton represents a common but poisonous mutation of religious practice: using religious vocabulary and claiming religious authority in the service of one’s own selfish, and often corrupt, purposes, all while claiming higher moral standing. In short, Norton represents the worst possible use of Christianity.

Contrast this with Andy who, as I argued in part one of this series, represents Christ himself. Andy represents goodness that isn’t defined or limited by institutions. Andy also stands in stark opposition to the rigidity, coldness, and evil embodied by Norton. Through this metaphor, the film proposes that one of Christ’s purposes is to overthrow the hypocritical leaders who profess to believe in him but use his image for their own gain. Andy does just this when he orchestrates Norton’s fall from grace after his escape from Shawshank.

The joke is on Norton. The tools that Andy used to thwart Norton were hidden in the very Bible from which Norton claimed to derive authority. There is a deliberate irony to Andy’s last message to the Warden hidden in the book, “Dear Warden, You were right. Salvation lay within.” Norton wouldn’t have been fooled had he ever simply opened his Bible. That Norton never did implies that he never really knew God’s word.

Again, it is somewhat discouraging that this is the most common representation of religion within film, but there is a lesson to be learned for the practicing Christian: claiming to act on God’s behalf in the service of one’s own unrighteous impulses is not just ineffective, it’s the embodiment of evil itself.