While I do try to write for an interfaith audience, I’ll acknowledge up and front that my own Christian history does color everything that I write here.

But today’s film marks a unique opportunity to speak a little more directly to other religious traditions. The titular character in François Dupeyron’s Monsieur Ibrahim is a Turkish, Muslim shopkeeper who becomes very important in the life of Moses “Momo,” a young kid living in 1960s France.

The first time we see 16-year-old Momo, he is literally courting prostitutes, who indulge in his request, which we assume is legal. We can have all sorts of conversations about what merits a spit-take in which culture under which context but … I’m supposed to keep these pieces under 1,000 words, so we’ll just save that discussion for another day and stick with the intended implication of the action: Momo sees romance as purely transactional, which signals his emotional immaturity.

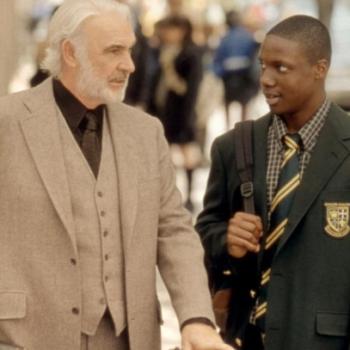

Many of these ill-suited beliefs, we are led to believe, grew under the neglect of the house he grew up in: his mother ran off years ago, and we can recognize his father experiences depression and has absolutely no tools to address it. Momo needs emotional investment from someone in a position to guide him, which is where Monsieur Ibrahim (played by golden age Hollywood icon, Omar Sharif, in one of his twilight film roles) steps in.

There are several divides between Momo and Ibrahim. Momo is generations younger, and Ibrahim hails from a different country and practices a different religion. But Ibrahim is shown to be exceptionally sensitive and discerning to the young boy’s needs. At the start of the film, Ibrahim is wise to the fact that Momo and his father are tight on money, which is why he permits him to steal from his shop. Momo comes to respect Monsieur Ibrahim, then gradually, to depend on him. After his father disappears, Ibrahim undertakes the legal proceedings to legally adopt Momo. Many of Ibrahim’s life lessons are of the romantic variety, but he also helps Momo to have a healthy relationship to his community or to see his potential. We are meant to understand that Momo will flourish throughout his life thanks to the care Ibrahim extended to him.

Ibrahim attributes his worldview to his faith in the Qur’an. His shepherding of Momo, then, takes on a dimension of religious devotion. Over and over he returns to the phrase, “I know what’s in my Qur’an,” as the reason for the peace he feels. Ibrahim takes Momo to his home country where Momo gets to see his religious observance up close. The potential barriers between these two characters reveal the universality of the human condition, including our capacity to extend and need to receive genuine love.

I’m always interested in celebrating “love stories” that have nothing to do with romance. That’s not a slight against the genre, one of my all time favorite movies is Titanic, but I do think we do ourselves a disservice when we define the subject as relating only to those who have the potential to satisfy us sexually. This is one of the reasons I am drawn to situations like this, whether the relationship is a more combative type, like in The Boy and the Beast, or more gentle like this. Because as this film proves, love knows no barriers.