Today’s film stretches back to classical film and love lost to war. The 1940 version of “Waterloo Bridge” likens the deathly consequences of one woman’s shame to the cataclysm of war, in doing so it makes a statement on the devastation that shame can reap on a human soul.

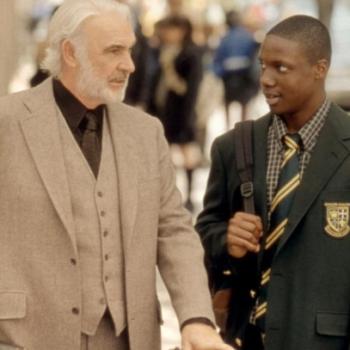

This 1940 romance follows Myra (Vivien Leigh) and Roy (Robert Taylor) as whirlwind lovers torn apart by the first world war. Myra and Roy meet on Waterloo Bridge just as an air raid overtakes London and they are forced underground, where they strike up a friendship. Myra is a performing ballerina and Roy is a soldier about to ship out to the warfront. They have a short but passionate romance and even try to arrange to be married before Roy leaves, but are unable to secure a venue or a minister. And so, they vow to find each other again once Roy has returned from battle.

By this time, her romance with Roy has already cost Myra her spot on the stage, and when she receives word that Roy was killed overseas, Myra is devastated. Grief and desperation drive Myra into prostitution. A year later, Myra finds Roy returning home from service, alive and well after all. Roy is overjoyed to see her again, but Myra’s relief is tinted by shame. She desperately wants to share her love with Roy, but what is her love worth after selling it to strangers for money?

Roy takes Myra home with him to meet his family, but their warm embrace of her only exacerbates her feelings of inadequacy. Don’t they know she’s not the wholesome girl Roy thinks she is? Overwhelmed, Myra sneaks away and returns to Waterloo Bridge, where she and Roy first met, and she walks straight into oncoming traffic, taking her own life.

One of the reasons why this film works so well as high melodrama is that it’s rife with the cruelest irony: the war tears Myra and Roy apart but not by killing Roy in combat, the adoration that swarms Myra only makes her feel more toxic, and Myra eventually kills herself believing she is doesn’t deserve the love of a man whose love for her was unconditional.

Roy eventually finds out about Myra’s history, but his feelings for Myra are unchanged. Her reservoir of guilt, and her eventual suicide, might have been avoided had she simply been honest with Roy. And therein lies one of the film’s wisest insights: shame festers and grows in silence and isolation. Myra’s feelings of guilt and unworthiness only ossify as she continues harboring her secret.

A couple of spiritual lessons stand out here in regards to shame over a transgression. The first centers on the false narratives that arise around the transgressor in response to fear and guilt. Myra believes that Roy will not love her after what she’s done. We the audience know this to be incorrect, and we agonize when Myra conceals this painful reality from Roy because we know how confiding in her lover might bring her peace and help begin the healing process. When wracked with guilt over mistakes, it helps to have trusted individuals with whom we can safely share and process our feelings.

Which brings us to the second application: we as striving disciples have a responsibility to be that safe base for other people. Before departing Roy’s family home, Myra does confess her history to Roy’s mother, and while she doesn’t overtly shame Myra, she doesn’t make much of an effort to rescue Myra from her mental wreckage. Emotional pain brought on by transgression abounds in a fallen world, and we owe it to each other to not add to one another’s strain.

I’m choosing to spotlight a film like this because it’s a simple truth that none of us will make it out of this life without accruing sins or transgressions of some kind, and I feel it’s imperative that we have a healthy understanding of how the repentance process works. Making mistakes doesn’t devalue us or make us less worthy of love.