“When the day of Pentecost came, they were all together in one place. Suddenly a sound like the blowing of a violent wind came from heaven and filled the whole house where they were sitting. They saw what seemed to be tongues of fire that separated and came to rest on each of them. All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues as the Spirit enabled them.” – Acts 2:1-4

I suspect that you may be wondering why an article on confirmation has begun with a quote about Pentecost. I hope that the connection will become evident as I proceed.

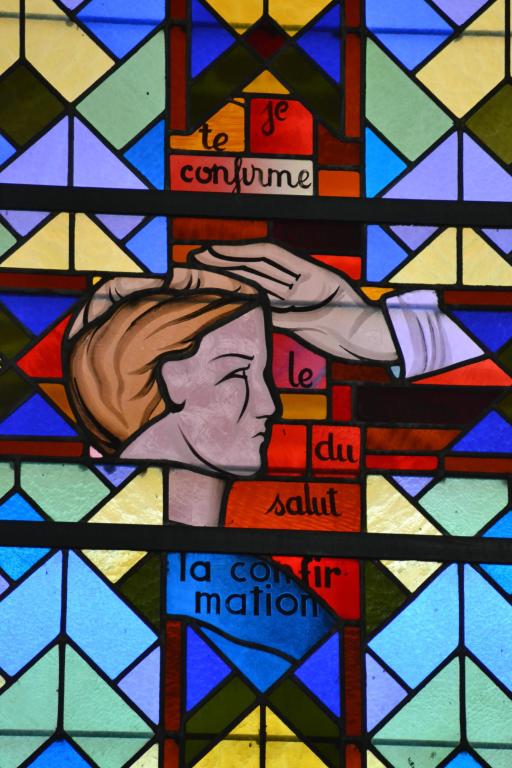

In my previous article, I had begun a discussion of the sacraments of the Catholic Church, starting with baptism. I now turn to the second of the three sacraments of initiation, confirmation.

From baptism to confirmation

Where baptism frees us from the bonds of original sin and makes us members of the body of Christ, which is the Catholic Church, confirmation is intended to strengthen and deepen the effects of baptism. I will begin by defining the Sacrament of Confirmation, the biblical basis for it, the history of confirmation, and finally, the significance and necessity of confirmation in the life of the Catholic.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church tells us that the sacrament of confirmation is “the special outpouring of the Holy Spirit as once granted to the apostles on the day of Pentecost”, and “brings an increase and deepening of baptismal grace.”

I hope now we can see the connection between Pentecost and confirmation. For just as the apostles received the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, so to do we receive the Holy Spirit at confirmation, and in so receiving, build upon the Graces received by baptism.

The word confirmation comes from Latin and is defined as making firm or establishing. Indeed, confirmation makes firm and establishes that which began in baptism. Confirmation is said to mark the individual as a witness of Christ and seals us with gifts of the Holy Spirit. Those gifts are counsel, fortitude, knowledge, piety, wisdom, understanding, and fear of the Lord. These gifts are meant to be used by Catholics to glorify God. In baptism, we are ushered into a new life in Christ. In confirmation, that new life is strengthened and perfected.

Confirmation in the Bible

I would like to touch here on the tradition of taking a confirmation name. At various points throughout the Bible, God renames individuals. Think of Abram becoming Abraham (Genesis 17:5), Jacob becoming Israel (Genesis 32:28), or Simon becoming Peter (Matthew 16:17-18). Do not think that receiving a confirmation name comes without a price. The biblical figures whom God renamed were also sent on mission. So it is with us.

The Bible provides several references related to confirmation. We read in Hebrews 6:2 of “the laying on of hands,” a practice intended to invoke the Holy Spirit. Most explicitly, we read in the Acts of the Apostles, “When the apostles in Jerusalem heard that Samaria had accepted the word of God, they sent Peter and John to Samaria. When they arrived, they prayed for the new believers there to receive the Holy Spirit because the Holy Spirit had not yet come on any of them; they had simply been baptized in the name of the Lord Jesus. Then Peter and John placed their hands on them, and they received the Holy Spirit”.

The placing of hands on the one to be confirmed remains significant today. During the confirmation process, a bishop will extend his hands over those who are to be confirmed, pray that they may receive the Holy Ghost, and anoint the forehead of each confirmand with holy chrism in the form of a cross. Chrism or oil has a special place in Biblical history. The Old Testament describes rituals in which priests, prophets, and kings are anointed with oil.

More than a symbol

Lest we mistake the anointing as simply symbolic, Saint Cyril of Jerusalem reminds us that, “For just as the bread of the Eucharist after the invocation of the Holy Spirit is simple bread no longer, but the body of Christ, so also this ointment is no longer plain ointment, nor, so to speak, common, after the invocation. Further, it is the gracious gift of Christ, and it is made fit for the imparting of his Godhead by the coming of the Holy Spirit. This ointment is symbolically applied to your forehead and to your other senses; while your body is anointed with the visible ointment, your soul is sanctified by the holy and life-giving Spirit. Just as Christ, after his baptism, and the coming upon him of the Holy Spirit, went forth and defeated the adversary, so also with you after holy baptism and the mystical chrism, having put on the panoply of the Holy Spirit, you are to withstand the power of the adversary and defeat him, saying, ‘I am able to do all things in Christ, who strengthens me.”(Catechetical Lectures, 21:1, 3–4 [A.D. 350]).

It was common during the early church to celebrate the three sacraments of initiation during the same ceremony. This practice began to change in the fourth century as more and more people were being baptized, and it became impossible for bishops to preside at every baptism. Over time, bishops began delegating baptisms to priests. The bishops retained the function of the laying on of hands and the anointing of the oil, which would be done separately from baptism.

Graces received are meant to be Graces rendered. The metaphysics of God’s Grace increases in the measure that we give it away. Having been consecrated by the chrism of confirmation and given the gifts of the Holy Spirit, we are now to give that Grace away so as to bring others to God.