My father was originally protestant, my mother originally Jewish, and our whole family eventually became Catholic, so I grew up with a hodge-podge of religious traditions, and loved it. I identify as a Catholic Jew because it seems the only honest way to describe my religious roots, my understanding of how I relate to God, my place in a larger story. Being baptized into the Christian religion and partaking of Catholic communion never made my Jewishness go away. There is often a lot of stress on the idea that Judaism is a religion and not an ethnicity, but I can’t ignore the ethnic dimension since I’ve spent my entire life dreading that I inherited the Ashkenazi breast-cancer gene from my mother. Being baptized doesn’t chase these things away.

However, I realize this puts me in a strange place. Throughout my entire life, I have had Catholics inform me that no, I can’t be Jewish if I am Catholic (is there such a thing as goysplaining?) – but I don’t really care what they think on the matter. I’ve even had Catholics inform me that I’d better not be practicing Jewish rituals in hopes that these rituals will save me, because that way lies damnation – proof that anti-Semitism is still a problem, and proof, also, that a lot of Catholics don’t bother to find out much about Judaism before pronouncing on it.

I care more about the perspective of Jews who might see me as trying, not exactly to appropriate a religious tradition, as trying to drag it with me, unsuccessfully, into other purlieus. This is especially significant since, historically, the Christian stance towards the Jews has not always been ideal; it has indeed often been shameful. I don’t know whether I should sit down and try to make the two parts of my identity have a dialogue, or whether the one part should be constantly apologizing to the other, or whether this would just be a narcissistic evasion of the issue. At any rate, I recently celebrated Easter and will soon be celebrating the Passover Seder (not a Christianized version, either). I also think it would be wonderful to have a Hebrew Catholic rite.

This article on why Christians should not host their own Seders made the rounds recently, and is worth reading. It made me think a little bit about the extent to which I, even with my Jewish heritage, need to be careful about the way in which I mingle my two traditions. The Christian tradition sees the Old Testament prophecies and pointing obviously to Christ, but perhaps sometimes we make too much of this supposed obviousness, and thus do an injustice, both to the early Christians who struggled to understand so many mysteries and surprises, and to centuries of Jewish traditions of reading these texts within specific – and sophisticated – hermeneutics.

This brings me to the whole question of cultural appropriation. It’s a term that gets bandied about any time one group of people is enjoying something from a tradition not their own, and it gets sneered at a lot by those critical of liberal elitism. I think it is important to understand that cultural appropriation is real, what it is, and what it isn’t, because when it is real it is an ethical and religious issue, but when it isn’t real we end up denying ourselves cultural enrichment on the basis of over-sensitivity.

What cultural appropriation is not: the adoption of elements from another culture. If this were verboten, we’d have no culture at all, because culture develops through exchange and encounter, just as persons do.

An adoption of elements from another culture is cultural appropriation if:

- The adopting culture is in a position of privilege or supremacy over the other.

- Those doing the adopting are doing nothing to exchange their privilege for the elements adopted, but merely taking what they want.

- The adopting culture does not actually value those in the other culture as persons, or even truly value their culture, but just wants to borrow aspects of it that look fun to them

- There is no attempt to truly educate oneself in the meaning of cultural elements in their original context.

This article from The Atlantic does a fair job of distinguishing between offensive appropriation and legitimate cultural exchange, emphasizing the importance of engaging with other cultures on more than an aesthetic level, and giving due credit to the cultures of origin.

To take it out of our immediate cultural context, go back a century to when the British were still colonizing India, and consider the extent to which white imperialists were happy to grab up all they could of exotic Indian dress, tasty Indian cuisine, and even their own bastardized version of what they took to be Indian religion – while at the same time denying full rights to actual Indian persons.

Recognizing that cultural appropriation is real doesn’t mean there aren’t grey areas. I am aware of this especially since I love to cook foods from other cultures, and practice the dances of other cultures. I do crappy hip-hop dancing in my basement for fun and exercise, and I think that’s probably okay, but is it okay when a white female rapper twerks to draw on the hyper-sexualization of black women by white culture, in order to make money, without actually entering into solidarity with what real black women experience as a result of this hyper-sexualization?

The religious issue of cultural appropriation is significant for many reasons, but here I want to highlight two:

First, it is very tempting for people to steal elements of a religious tradition that look fun without entering into any of the discipline and spirituality entailed in that religion. This has been done en masse to Christian traditions by American secular culture (Mardi Gras….Easter Bunnies…Santa Claus). While Christians are not an oppressed or marginalized demographic in America, the irony is that the false, appropriated versions of our feasts have flooded the market and come to be mistaken for the real thing. Increasing commercialization of religion inhibits genuine cultural flourishing, and in case we have perhaps inhibited ourselves. In recent culture-war squabbles over holiday representations, Christians might get a more sympathetic ear if we were to celebrate our feasts more authentically, as part of our commitment to our ongoing story of redemption, not to the made-in-China plastic panoply of trivialized ritual.

Second, it may be that we need to do an examination of collective conscience as we regard our historical views of other religions. Have we, in a misguided but well-intentioned drive to evangelize, appropriated the traditions of other religions, using force rather than love in our efforts to share our faith? Because I like dappling in mythography, I am constantly delighted to find the different threads of belief, archetype, symbol, hope, and fear that run through varying religions. We have so many common stories and shared religious ground. But there is a darkness underlying this delight, because these connections often come with tragic consequences. The study of the history of religion reveals layer upon layer of borrowing and sharing, but also, unfortunately, forced conversion or repressed custom. Christianity has too often been connected with white supremacy, racism, imperialism, and manifest destiny, and this is a horrible violation of the message of Christ, the body of Christ, the wounds of Christ. Perhaps God does indeed work mysteriously through the turmoil of history, but the divinely comedic flowering of good from evil doesn’t lessen our responsibility for evil. It should just make us more humble.

It is strange to see that Christianity has often flourished most strongly in black communities, among people who had Christianity thrust upon them, but for whom Jesus became more present than in the midst of wealth and power. It must be strange for practicing Jews to see Christians take the Passover meal and make of it something wholly different. When you stop and think about it, religion is a strange thing across the board – and a very human thing. So, as we ask others to be respectful of our belief and worship, we need also be respectful of the religious integrity of the persons who practice other religions, who hold them sacred. We need to remember that even if cultural appropriation is the way the world turns, it is a way of power, not a way proper to a Christian.

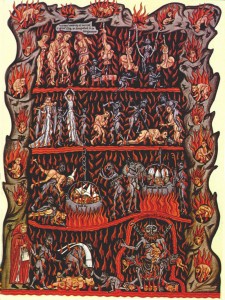

Image is of Jews being burned in hell. Image credit: Hell, 1180, from the Hortus Deliciarum. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hortus_Deliciarum_-_Hell.jpg. Published in the US before 1923 and public domain in the US.