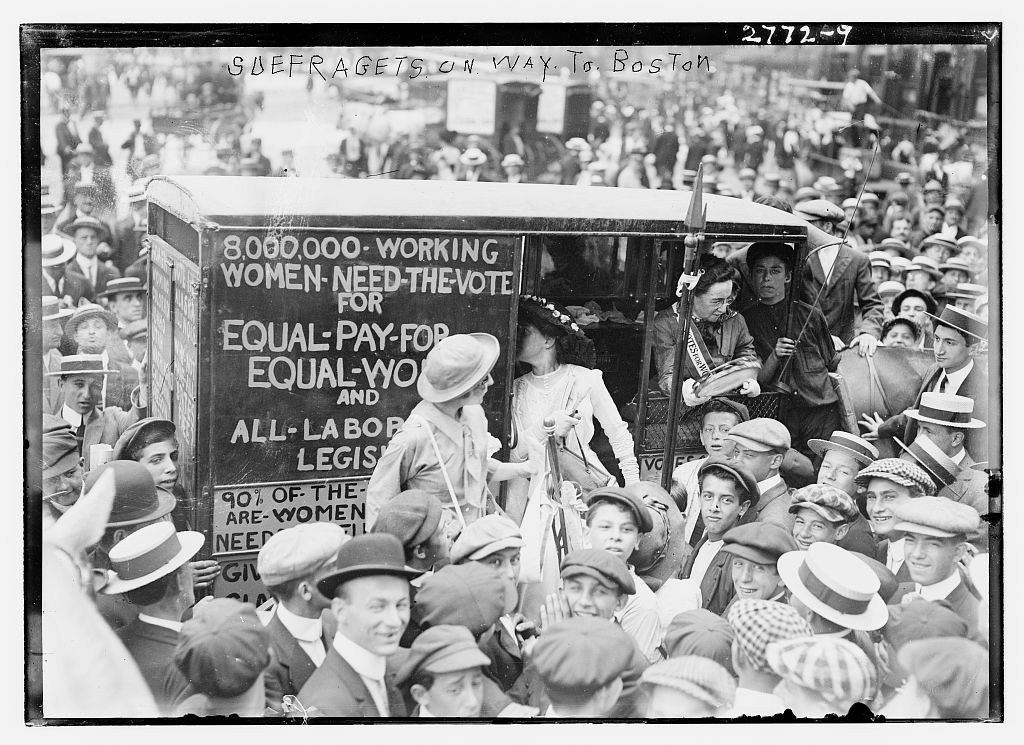

So, today – March 8 – was International Woman’s Day. It was originally celebrated as International Working Woman’s Day, and has a complex history, associated with both labor movements and women’s rights movements. It was on this day, in London, in 1914, that famed suffragist activist Sylvia Pankhurst was arrested while taking part in a march for women’s voting rights. ” Now, over one hundred years later, many are of the opinion that the goals of feminism have been met, and that women who protest today are just “whining” or “seeking attention.”

“I would have stood with the suffragettes” they say, “but the suffragettes would have nothing to do with this crowd!”

Well, I am not so sure. I suspect that if you are of a mindset that regularly mocks and dismisses social justice movements today, you would have done likewise in the past. If you gloat over the prospect of running over BLM protesters who block traffic, I expect you would have supported the imprisonment of Dr. King in the Civil Rights days. If you’re passing around memes mocking contemporary feminists, you are the type who would have applauded the arrest of Pankhurst in 1914.

This is not to say that there aren’t criticisms to be made of various women’s movements today. It is often feminists themselves making these criticisms, actually: in my case, I am deeply critical of the idea that abortion is a valid or just solution to the problems women face. I think this is a case of a deferred scapegoating, a passing of the buck of injustice, and it is especially problematic because of the invisibility of the victims. And I am not the only feminist to think this way. Pro-life feminism is real – and, typically, a lot more pro-life than its non-feminist counterpart.

I am critical of white, liberal, capitalist feminism that privileges the desires of the comfortably well-off over the responsibility to the most vulnerable. Imagining women’s equality in terms of corporate or political power often means buying into imperialist models that depend for their existence on environmental degradation or colonial exploitation.

I am critical of forms of feminism that leave no room for religious expression, because for me my Christianity and my feminism go hand in hand, and for many women of different cultures, religious and spiritual traditions are a rich part of who they are, and how they understand their womanhood.

I am even critical of the women’s strike that took place today, and not because I think feminism’s goals have been met, or that women don’t face injustice. While I am sympathetic with the goals of the strike (with some contingency on how one interprets the phrase “reproductive rights”), I am not sure that it ultimately serves the purpose of altering the conditions of women in situations of profound injustice. If a few corporate women succeed in breaking the glass ceiling, how much difference can that really make for a woman who faces a crisis pregnancy, or is forced into sex work?

But what does it mean for women to go on strike in 2017? In an earlier era of highly segregated career paths, a “women’s strike” had a specific, tangible effect: It made invisible work visible. No women meant no food on the table, no mysteriously emptied trashcans, no one to change diapers or type letters. No women meant no sex. (Yes, going Lysistrata is a real thing—and it occasionally works.) Forcing men to handle “women’s work” was the only way to get those men to admit that it existed.

In a response to Doyle, Magally A. Miranda Alcazar and Kate D. Griffiths write, in The Nation:

Last September, brave women in multiple facilities participated in prison strikes through the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee . The Standing Rock Water Protectors have dramatically fought the invasion of the Dakota Access Pipeline into indigenous lands, and are led by women. On February 13, as many as 10,000 immigrants rallied in Milwaukee—a demonstration led by women—walked off the job for a local “Day Without Latinxs, Immigrants, and Refugees,” which was followed by striking workers and students across the country on the February 16 “Day Without Immigrants.” These demonstrations hark back to the General Strikes of 2006, where hundreds of thousands of women participated in that year’s Day Without Immigrants, one of the largest strike actions in US history. A large number of those strikers were women working in precarious jobs and with few legal protections.

So, okay, perhaps my criticism of the stike itself comes from a position of relative privilege: the privilege of a woman who has something to lose. It often is the most disenfranchised who lead the way in reform, and often in past movements they have made common cause with those in leadership who have visibility and resources. But still: a “Day without Women” is intended to increase the visibility of the work that we do on every level of society, but will this make any difference for those who were invisible before, and will remain invisible after?

I think this is a good conversation to have, among feminists, and with those who do not identify as feminist. It’s also valuable to converse about the extent to which differences on the abortion issue create an unbridgeable gap between different activists, or whether there are ways we can find common ground for ending the injustices that drive women to seek abortion.

That being said, there are a few things many of us are tired of hearing, every single time women band together in any form of activism. These remarks are especially eyeroll-inducing when they come from people who claim to respect women, or be in favor of women’s rights.

“Real women don’t….(fill in the blank with whatever it is that feminists are doing).” Just enough with the “real women” stuff, okay? Over the course of history real live women, authentically female women, have done a remarkable variety of things. And not always the things that you imagine “real women” do. You can talk about virtuous women, intelligent women, practical women, responsible women, courageous women, but drop the “real” nonsense. You can drop the “real men” nonsense, too, while you’re at it.

“What women really want…(something about what you imagine traditional gender roles to have been).” Yes, some women like staying at home, being domestic goddesses. Some women love having lots of babies. Other women hate housework, prefer to have someone else cook for them, and don’t feel especially maternal. Some women are called to the religious life. Other women are driven especially to work in the world, as doctors, reformers, teachers, artists – or as cooks, decorators, caregivers, or other traditionally “feminine” jobs. Many women are a mishmash of all of the above. Some women experience illness or disability, or rampant social injustice, and face the reality that they may not ever get what they desire. Some women prefer men who are more in touch with their feminine side; other women prefer men who know how to cut down trees and rope cattle. But when a woman says she prefers a man to boss her around, the term “Stockholm Syndrome” crosses my mind. Consent, after all, is not the only requirement for an act to be moral.

“Women are losing their uniqueness by pretending to be men.” Slow down there a minute. First of all, we really are not pretending to be men. Wearing trousers, competing in the workplace, having opinions: these are all things we can do AS WOMEN, believe it or not. There is no fundamental male claim on these activities. If you mean “have babies” – well, not all women have babies. Are these women mysteriously less unique? Secondly, “losing their uniqueness” impies that personal uniqueness is some kind of mask or accessory, that can be lost. That’s not how it works with the whole personhood thing.

“Feminazis.” Yes, because wanting equal pay and not to be raped is totally like committing genocide. Next?

“No man would want to f*** you.” Tell that to the many women marching who have children. Anyway, dudes, it’s entirely possible that you and your rutting are not actually this amazing prize-for-being female that any woman wants. There’s a pretty good chance that we’re relieved that you’re not lusting after us. But thanks for demonstrating where your priorities lie.

Of course, there’s no moral obligation to support every women’s movement, or refrain from criticism. But if your response is a variation on the above – or an attack on the appearance of the women involved – or a suggestion that feminist activists must be anti-home-and-family – don’t expect to be taken seriously when you say “oh, yes, I respect women!” What you mean is “I respect women so long as they act in accordance with a very narrow modern western ideal romanticized on TV and irrelevant for most of the history of civilization.” Which, incidentally, is not the kind of approach to the person – male or female – that Christ modeled.

image credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Suffragettes_EnRoute_To_Boston_3820613246.jpg