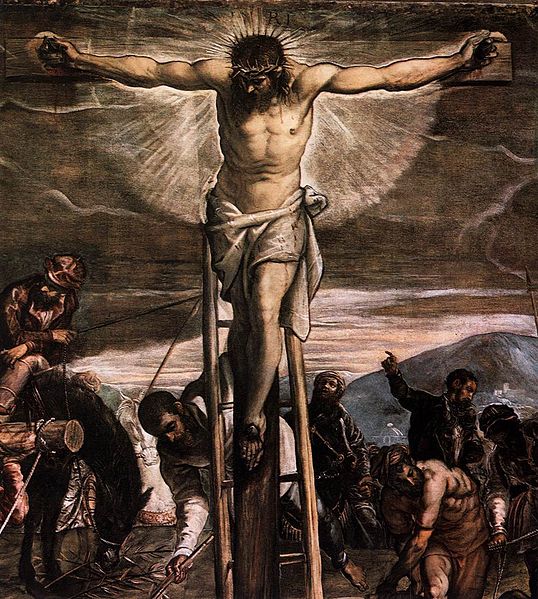

How did the cult of “positive thinking” ever get even a toe-hold in a religion founded by a man who was tortured and executed as a criminal traitor in his early thirties, never having held an office or achieved wealth? His disciples forsook material wealth and political prestige in order to follow the counter-cultural Gospel of the crucified God, and many were imprisoned, tortured, and executed in their own right.

If you want to save your life, lose it. Turn the other cheek. Give all you have to the poor. And yes, there will be rewards, but they will not be earthly rewards. Anyone who had joined up with the Christians in hopes of winning the prosperity prize would have been sorely disappointed. Even beyond the persecutions of the imperial state, the very organization of early Christian society was radically egalitarian, their property distributed to help the less fortunate. And this was not just in a socio-economic arrangement, but a vision of human relationship in church, in Christ:

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free person, there is not male and female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus

Those who complain about “elites” ought to find here the ultimate anti-elitism, theologically as well as practically. But complaining about “elites” is really just a sort of tribal signaling, because those who do it are dedicated to forms of elitist discrimination on the grounds of race, nationality, sex, or religion.

And these are the same who reject Jesus’ teachings on the poor, and the church’s teachings on our societal obligation to the poor, in favor of economic libertarianism linked with a specious theological triumphalism, according to which our reward for following Jesus (even though we’re not following Jesus) is to be here on earth. Thus the ressentiment when some earthly power interferes with what was, in their mind, their due, according to a divine plan for prosperity and power. To be taxed is to be robbed, in their minds, not only because they acquired it via the “free” (pardon the scare quotes, but they are needed) market – but because this prosperity was promised them, they believe, by God.

This faux Christianity is part of the Trump creed. Not a large part, because he’s not given to God-talk (distracts too much from how great he himself is, I suppose) –but, definitely enough of a cog in the messy machine to give other practitioners of faux Christianity a tiny toe to balance on, when they claim that he’s a God-fearing man. His church, growing up, was the church of famed prosperity-gospeller Norman Vincent Peale, who popularized the idea of the “power of positive thinking”:

“When he went into church on Sunday,” Hamilton says, “[Fred Trump] would hear his minister telling him stories about if you have positive thinking, if you’re faithful, if you’re upholding your family and your community, then that’s what unleashes the power that’s made you successful.”

Peale, who died in 1993, rarely talked about salvation. His message was more practical than theological. It echoes today in what’s known as the Prosperity Gospel, practiced by megachurch televangelists who favor spectacle and say God chooses to reward some people with material wealth.

Those of us who watched with incredulity as, row after row, talking religious heads succumbed to the Trump spell, were perhaps, hitherto, insufficiently aware just how corrupted American Christianity had become, and how this corruption has entered Catholic culture, too.

Once one becomes aware of it, though, it’s impossible not to notice, and I don’t just mean in overt cases, like when people actually take Joel Osteen as anything but a joke or menace. It’s there in the “I can do it” memes. The poor-shaming. The fiscal libertarianism (though not social libertarianism, because otherwise there’d be no sexual transgressors to scapegoat). The worship of “wealth creators” (Dante would have a thing or two to say about that. In his Inferno). The selective sharing of saint’s quotes: forget the Church Fathers reminding us that our extra goods belong to the poor; here is St. Josemaria Escriva telling us “don’t allow those around you to be pessimistic.” Depressed people are a downer. Poor people are a downer. Fat people are losers. Convenient amnesia about one’s own history: the assistance from family during hard times; the connection that enabled one to get free tuition; the close-knit community that helped during times of sickness. Convenient amnesia about one’s own past failures: drop-outs, firings, unplanned pregnancies, delinquencies? Never happened. Mind wipe.

It’s there in the Benedict Option: we lost some war, so we must retreat and save ourselves – forget about what Jesus said about loving or enemies, or about war in general. As Jonathan Ryan points out:

We must incarnate in the world and be a part of its pain and redemption, even if it means we could lose our way from time to time. This all sounds dangerous. It most certainly is. But that’s the call of Christ–not a call to “protect Western Civilization” or “Christian culture,” but a call to risk it all for the sake of the redemption of the world. We must risk our children as we teach them to engage with sinners like themselves. We must risk our self respect, our reputations, and everything we hold dear.

This is a hard theology, but one that can accompany us into the worst of places. But these tame little vanilla theologies of prosperity: once they are taken, on their leashes, outside the bounds of the little gated spiritual communities in which they are coddled, how can they survive?

It is strange to contemplate how those who profess, overtly or covertly, a prosperity gospel, must experience the story of the Agony in the Garden, or the hagiographical details about the lives of the saints. Because when I look at the darkness and suffering which God never said he would take from us – which the Father did not even take from the Son – I am terrified. And a little angry. I don’t understand this life in which Christ came and was crucified for our sins, and instead of saying “the ultimate sacrifice has been made” we keep demanding more and more sacrifices from one another, keep creating scapegoats, keep crucifying Jesus over and over. This should not have been necessary.

I am so far from seeing anything but deluded farce in the “prosperity gospel,” I have trouble even accepting theodicies that do recognize the physical evil to which we may be subjected. I have never yet met a theodicy that explains the Holocaust, for instance. Nor even one that can render acceptable the pain of a child dying of cancer while parents stand helpless by. Confronted with the utter opposite of prosperity, I am tempted to abandon all hope, sometimes, except that I run up against the need to make an existential choice.

Either this world with its horrors, wars, rapes, genocides, diseases, and natural disasters is all there is, and all this suffering goes unmended.

Or there is some mending that will transpire, something beyond anything I can now comprehend, beyond any stupid theodicy. It is in this darkness, not in any blaring projection of cash-flow fantasy, that I find the tiny whisper that is, I think, and I hope, God. And so I surround myself, often, with the morbid and the weird, with the ones who like me have doubts and inappropriate thoughts, bad dreams and bizarre recollecitons. We can talk about how crazy we feel sometimes. We find Christ in the strangest places. We see the skull beneath the skin but also the rose in the blood.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jacopo_Tintoretto_-_Crucifixion_(detail)_-_WGA22517.jpg