I’m still having difficulty knowing what to do with my anger and sorrow over the shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue last weekend, and I can’t begin to fathom how those near to the victims are managing from one minute to the next. And thinking about this is like a ghastly connect-the-dots as my imagination moves from one tragedy to the next. I’m thinking of the thousands of desperate families in the refugee caravan. I’m thinking about those dying of famine in Yemen – and largely due to the fault of the United States, which has supplied arms to our Saudi friends who are carrying out this ongoing genocide.

We all need breaks, from time to time – especially those who have experienced trauma, or suffer from physical or mental illness. But I keep thinking about how there are so many for whom there is no relief in sight. And it seems frivolous and irresponsible to ignore what other human beings are enduring. If they can suffer it, and keep going, isn’t it a kind of privilege to say “oh, I can’t look at that right now. I can’t deal with that right now”? – simply because we don’t want to have our fun disrupted? Escaping into a pastel-tinted fantasy world of cute puppy memes and shopping trips seems nauseatingly lukewarm.

“Make Facebook Fun Again,” says one meme. Yes, we’re spoiling everyone’s jollies by reminding them of what’s going on in the world today. “Look on the bright side!” one Facebook commenter told me and a Jewish friend who were worrying about the rise of anti-semitism.

You want Nazis? Because this is how we get Nazis.

It makes me aware of how totalitarian regimes succeed. Not because people are evil, but because they’re just so nice, so respectable, so unwilling to make a scene and confront reality. I’m reminded of the deadly danger of sentimentality, the stirring up of emotions with no relation to any proportionate object, so that the pleasant haze of false feeling obscures reality, even the real passions that arise in relation to real demands made on the heart, the will, the mind. A work of art or an image is not sentimental simply by virtue of evoking deep feelings – even Aristotle would scorn that idea – but it is sentimental if the feelings are untethered to reality, or if one is left with the sense that having responded with feeling is sufficient.

Dostoevsky says of the loathsome father in The Brothers Karamazov that “he was sentimental. He was wicked, and sentimental.” These two attributes go together, hand in hand, just as kitsch art and ersatz emotions are the hallmark of tyrannical regimes. Kitsch art distracts us, engages our most superficial emotions in a fluffy make-believe world. Propaganda art isn’t all dehumanizing images of the “other”: it’s also heroic representations of Dear Leader and sentimental portrayals of the Perfect Blond Nuclear Family.

When it comes to religious art, it’s almost a guarantee that a person who loves saccharine, blond holy-card representations of the Virgin Mary will also spew hateful vitriol about immigrants, Muslims, the poor, and anyone who doesn’t fit into their spiritual gated community of the white western middle class.

Sentimentality and Emotional Demands

A scale of privilege dictates which emotions we are obligated to take seriously. I’m reminded of the many admonitions to try to understand why white working class men might be angry – from people who remained at best indifferent to the anger of marginalized groups, mocking Black Lives Matter, demonizing angry women as “feminazis.” Some Anger Matters. Some Anger Doesn’t. Bourgeois respectability privileges the anger of those who are already in power, while that of those who are disenfranchised is viewed as disruptive, distasteful. It makes people uncomfortable, so it should go away. Happily, there will always be a cute puppy meme we can hide behind, so we won’t have to see it.

This is why authoritarian institutions are so frightened of “difficult” art that uncovers injustice and abuse. A novel like Jane Eyre may seem ladylike and classic to us now, but once it was a dangerous book. It made readers uncomfortable because it challenged prejudices about class, sex, gender, marriage, and religion. The softly artificial and conventional sentiments of the characters in power are undermined. The perspective of the small, insignificant protagonist is made central. Today, a novel like Lolita is treated as a forbidden text by fundamentalists of every stripe, sometimes because censors are too stupid to understand it, but often because it reveals too much: it reveals that the man in power, the one with the beautiful story and the authority to name and define, is a liar. His entire relationship, which he explains with such sentiment, such self-pity, is with a phantasm. In reality he is a rapist and an abuser. How many men – respectable, educated white males – are afraid of Lolita because it reveals them for what they are? In the era of #MeToo, I imagine: quite a few.

But people don’t want to face that possibility. Nor do we want to confront our own complicity, when we look away, in the actions of rapists and abusers. We want everything to be nice.

That’s how the domineering upper classes in Charlotte Bronte’s England succeeded in tyrannizing the poor and working classes. It’s how Humbert succeeds in convincing everyone – even his readers – that he’s the victim and the hero in the case. And it’s how authoritarian regimes, again and again, cement their power: by counting on the sentimentality and respectability of the ever-so-nice people who enjoy center stage, and just don’t want to deal with any unpleasantness.

To return to Dostoevsky: the statement that “beauty will save the world” in the same novel is one of those brilliant and somewhat enigmatic statements that has been reduced almost to the status of a puppy-meme with glib overuse. But I think if you put it alongside his representation of the sentimentality of Old Karamazov, you begin to see the contrast. The beauty that saves the world is not the pleasant, undemanding kind of prettiness that we escape into. It’s the beauty that makes hard demands of us, including the demand that we act – that we convert. We see this beauty on the face of the downtrodden, the immigrant, the starving child, the abused woman. If it saves the world, it’s because it tells us – like Rilke’s poem about the torso of Apollo – “you must change your life.”

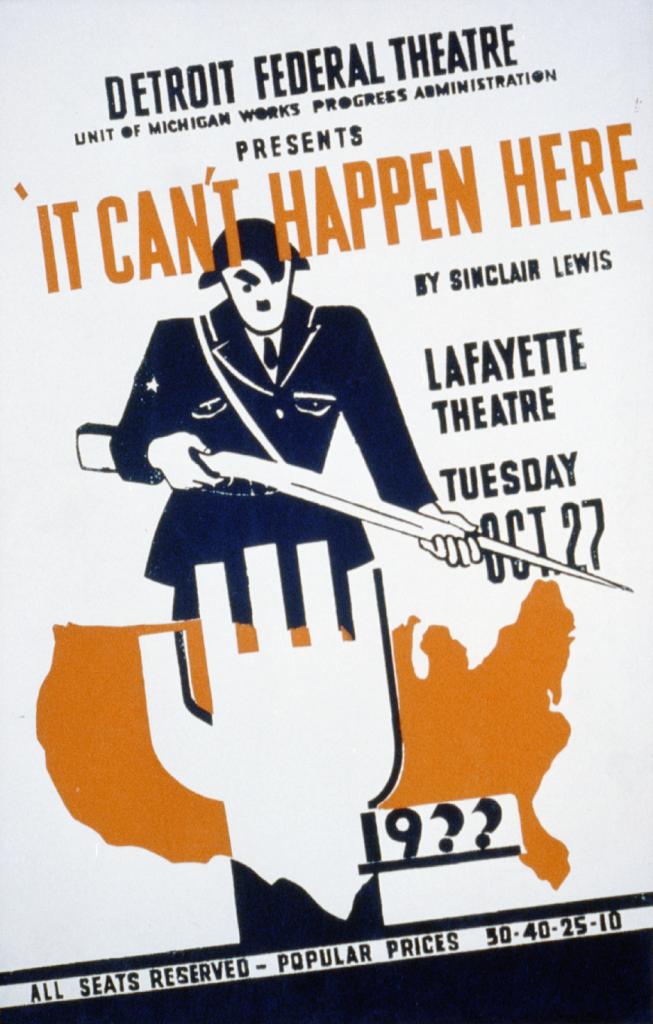

image credit:wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/40/Sinclair_Lewis_It_Can%27t_Happen_Here_1936_theater_poster.jpg