“Can’t we just drop it?” people ask.

Well, we could. The problem is, the story has reverberated beyond the initial encounter, so that it is now not so much about what happened in a particular complex cultural situation, and more about broad perceptions and the shaping of narratives.

And because of this, we owe the young white men in the video an apology.

No, I never doxxed, threatened, or called for violence against these young men. And I denounce the actions of those who did so, even if they were motivated by zeal for racial justice. Having just celebrated Martin Luther King Day, we have been reminded that hate can not drive out hate; only love can do that.

But, if we’ve been paying attention, we’ve also been reminded that the roots of racial injustice are deep, and its repercussions widespread. We’ve probably been reminded that as white people we too are complicit in structures of injustice even if we never intended to be – and that we have a moral responsibility to change that. Opposing hatred with love is not about free hugs, or avoiding conflict, or even always about dialogue – because there can be no dialogue where trust has been eroded by years of abuse, or where there is not good faith.

The immediate and visceral response which led to the demonization of this group of young men has been called “scapegoating” by many of their defenders. And their defenders are correct, in a way they perhaps to not intend: we have been scapegoating the young white men as sacrificial victims to atone for our own structural sins of racism, white supremacy, and colonialism, which we continue to perpetuate and which contribute to the actions and presuppositions of our young people.

Consider the way we think about our “right” to the land, to the extent that we justify violence against immigrants. We do this forgetting that if we live in this nation and are white, our ancestors were immigrants themselves, many of them coming over and appropriating native lands. If we think that this is not problematic, it’s because we’ve bought into white supremacist doctrines according to which we had a right to seize land from the “inferior” or “savage” Other. People who are angry because protesters told the white men “go back to Europe” need to ask themselves how they can object to this while at the same time thinking refugees have no right to come here onto “our” land.

Consider the way our history and literature are taught. How many people, reading the Little House on the Prairie books, noticed that the Ingalls family was essentially trespassing on native land, and that the objections of the indigenous peoples were portrayed as terrifying incursions on innocent white families? And this is just one of many instances. From Columbus to the present, we have sanitized stories of violent exploitation to justify the white Europeans. Christians don’t help when they justify colonization as missionary work, and brush aside atrocities with “well, at least we brought them Christianity.”

Our pop culture and entertainment don’t help. From old westerns to kids’ cartoons, the “Indian” is portrayed as anything from a menace to a figure of fun. Indian dances and chants have been presented, not as sacred ritual, but as goofy tribal behavior which white folks can participate in for our own entertainment, if we so desire.

Even stories seemingly sympathetic to indigenous peoples are white-centric. The white man goes among the natives and gets a native name, native glory, native weapons. Oh, and a native woman: because non-white and indigenous women are repeatedly hyper-sexualized and viewed as prizes for the white conqueror.

The fashion world has trespassed on native aesthetics and even sacred dress, simply in order to make money for white-owned corporations, and glamorize white women. The sports world has appropriated native imagery and caricatured indigenous persons, for amusement and for money.

We privilege our religious freedom in a culture in which we have stolen sacred lands from native peoples, and are scandalized at the idea that an Indian man might have attempted to get into one of our opulent churches, while we mock his own prayer rituals. We privilege white voices, so that it is always the white person who will be believed over the native person, or person of color. We don’t even bother to find out why Nathan Phillips and other native persons were present in D.C. that day.

What I found myself focusing on the most, in the past few days, was the way too many of my fellow-Catholics tend to speak about indigenous persons. I followed a few threads on different social media pages, and saw people revile Phillips’ prayers as “satanic.” I saw people call him a dirty old Indian. And even when the racism was not overt, I encountered widespread suspicion of the fact that he was a native activist – as though only white people are allowed to do marches and attend protests. And underlying so many statements, the assumption that an elderly native man must automatically be a threatening figure – even to a young man surrounded by fifty of his peers, with white adults on the sidelines.

This is the world we have grown up in, the air we breathe. We easily go through our lives accepting certain prejudices because we’ve never stepped outside our own circle and looked at things through the eyes of the Other. We appreciate native artifacts, relics, and art as though they are there for our tourist enjoyment. Which, it seems, is pretty much what the Covington Catholic boys were doing.

A minor incident in our nation’s capital has blown up into a major national debate, but for the most part our focus has been wrong, our fixation on a few poorly behaved young men brought up in a culture of white privilege and never given an opportunity to have their preconceptions challenged. Just like most of us, if we are white and middle-class.

Making this about the Covington Catholic students, instead of about a broader structural issue, allows us to avoid the responsibility we bear for re-shaping our deformed culture, in our schools, our churches, our businesses, and our media – as educators, as writers, as artists, as activists. As human beings.

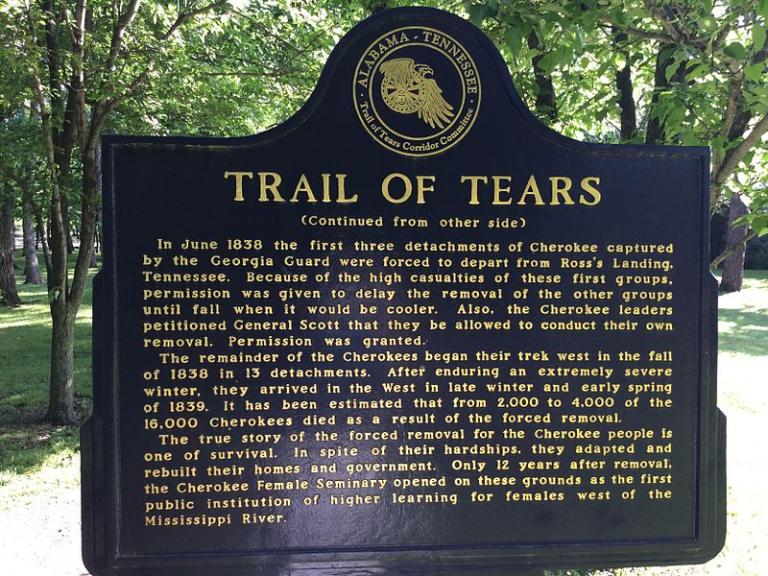

Our nation committed genocide against native peoples, stole from them, abused them, enslaved them. In this context, we have a lot of work to do, and much of it is the work of atonement.

image credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cherokee_Heritage_Center_-_Trail_of_Tears_plaque-rear_(2015-05-27_08.58.33_by_Wesley_Fryer).jpg