by guest writer William M. Shea, Ph.D.

Atheism in philosophy

I started working on atheism when it came time, in 1969, to decide on a doctoral thesis topic at the Columbia University School of Philosophy. I had previously been aroused intellectually by both Ludwig Feuerbach [1804-1872] and Jacques Monod (1910-1976), as much by the differences between them as by their common atheism. Ultimately American Naturalism became the specific focus after I had been seduced by George Santayana (1863-1952), the Harvard father of the academic movement, and I then turned to atheism’s American gestalt in its Columbia Naturalist version: John Dewey (1859-1952), Frederick Woodbridge (1867-1940), and John Herman Randall (1899-1980).

Santayana caught me, perhaps because he was the first Catholic atheist I ever read and surely the oddest of the American Naturalist philosophers. My mild obsession with atheism has lasted now over near fifty years. It forced me to rethink my Christian faith, at least to develop an ever deepened understanding of that faith. My past fifty years have been marked by a psychic tension between atheism and faith, fed not only by the philosophical issues but also by the affection I felt for these fine philosophers, by the evils I encounter in the world around me and by the violence that seems to be at the root of every existent thing. I have from childhood had difficulty squaring what should be with what is.

To state my position on it now as briefly as possible: Atheism fails me both as philosophical theory and, even more importantly, as a “way of life.” Catholic Christianity especially continues to engage me both as way of believing and as a way of living. Even with the current horrific moral mess the leadership of my church has created, I am not even tempted, as have too many of my brothers and sisters in the church, to desert what appears to be a sinking ship. Should the ship go down, I’ll be going down with it.

Now enters John Gray, a noted British philosopher. His Seven Types of Atheism (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018) renews the impact of Feuerbach, Santayana and the Columbia Naturalists. John Gray proclaims himself an atheist: “…an atheist is anyone with no use for the idea of a divine mind that has fashioned the world…It is simply the absence of the idea of a creator-god.” [2]

Unusually, however, Gray is an atheist who writes a criticism of atheists; he aims at a taxonomy of them, and he finds seven types. With Gray we can look a bit more analytically at the category “atheism.”

A taxonomy of atheisms

I have read over the past two decades several of his first type, the so-called “New Atheists” [Dawkins, Hitchens, et al.], with rapidly declining interest and finally no appreciation at all. There is nothing new there, nothing to be learned, and the antagonistic tone underlying three of the Four Horsemen is mean and makes me angry. Being as kind as I can I must say that their philosophical and historical writing on religion and God is intellectual trash. I’ve not managed to finish any of the many volumes by them and their epigones, party out of boredom, even more out of intellectual disrespect and, I admit, a conviction that they intend to insult me. They are without respect for me and my people.

Gray’ second category is Secular Humanists who have dismissed Christian monotheism and promoted their own myth of Progress in its place. Then there are the adherents of Scientism whose hope has been transposed into a mythic “scientific world view” and faith in the promise of Science. Wisely he remarks that science is a method, not a world-view. “Political religion,” his fourth type proclaims a hope in revolutionary action which, without God, will save humanity. Examples run from its root in 16th century Christian apocalyptic to Bolshevism and Nazism. Fifth, the God-haters’ [de Sade, William Empson] view the Christian God as “the commandant of Belsen.” [115f.] And, finally, there are the two types for which Gray expresses sympathy: those atheists who view history as without meaning, yet recognize religion as a natural response in human experience, and those who greet cosmic existence with silence [examples of these types are Santayana, Schopenhauer and Spinoza, 124-156]. The latter have a certain similarity to Orthodox negative theology and Christian mystics.

Gray fleshes out my own typology. My own has been that there are atheists who don’t get the point of religion and remain silent; there are atheists who do get it and respectfully argue with it; and then there are what Gray calls ‘evangelical’ atheists whose main concern is to turn the human world into a summer camp for atheists, inviting theists to grow up. I would place Gray among those who get the point of religion (a search for meaning}, don’t resent it but find its story-telling illusory, putting meaning where there isn’t any.

Encounter with mystery

Although a delightful and exciting read throughout (Gray is a remarkably sensitive interpreter of other thinkers), the most provocative insight that Gray articulates occurs here and there but especially in the last chapter of the book, namely, that the universe itself is a mystery. In our contemporary Age of Scientism and New Atheist arrogance this is a surprise. Many of the atheists to whose work Gray attends would never say “mystery,” at least not out loud and perhaps only under hypnosis, for fear of being misunderstood. Far from being a mystery, many atheists would say, the universe is obviously the result of chance and necessity, as Jacques Monod said thinking he had put an end to the age old question.

With this admission Gray, however, crosses a red line into a possible dialogue with believers. For I, too, find the universe a mystery as would other religious people, though many of us would capitalize Mystery. At least in common we might affirm that there is an intelligibility at stake, that is, that, deep down, existence either makes sense or it doesn’t.. As Gray asserts in the last words of his book: “A godless world is as mysterious as one suffused with divinity, and the difference between the two may be less than you think.” [158]

The intellectual significance of this, along with his attempt to allow some space in life to religion, is huge. After all, most of us less advanced folk still ask: Why is there something rather than nothing? Very mysterious indeed! The answer is mystery or Mystery –unless one wants to claim that one should not or can not raise that unsettling yet unavoidable question. Equally, regarding history we might ask: “What does it all mean?” With both questions we seem to want not only meaning [as Gray admits] but truth.

But does Mystery speak to our questions?

For Jews, yes. For Muslims, yes. For Christians, yes. For Christians like me Jesus is the speech of Mystery, the presence of God in history, the Word-made-flesh. Does Mystery speak as well in other religions? Yes, with due qualifications, is my opinion: Hindu and Buddhist [et al.] scriptures are not merely human speech as far as I am concerned. For the vast majority of human beings who have lived and do live on the planet, Mystery speaks. For Gray, at least the mystery remains even if it is deafeningly silent.

My own people (Christians) hear the deus absconditus (the hidden God, the “Mystery”) speak and we stick to what Gray deems an impossible historical fact: the death and resurrection of a specific human being. This is the deep difference between Gray and myself: for me, for us Christians, the Mystery is in fact in history though it remains mysterious. That Speaking continues in the church’s proclamation, has not withdrawn itself from history but is a dialogue rather than a monologue, primarily in community but as well as in the ecstasy of a solitary mystic. The Word and it’s Way are as much mine and Pope Francis’s as it was Peter and Paul’s. True, we too often and sadly distort it as they did but we don’t abandon it We hear Gray’s silent mystery as the God who speaks a Word.

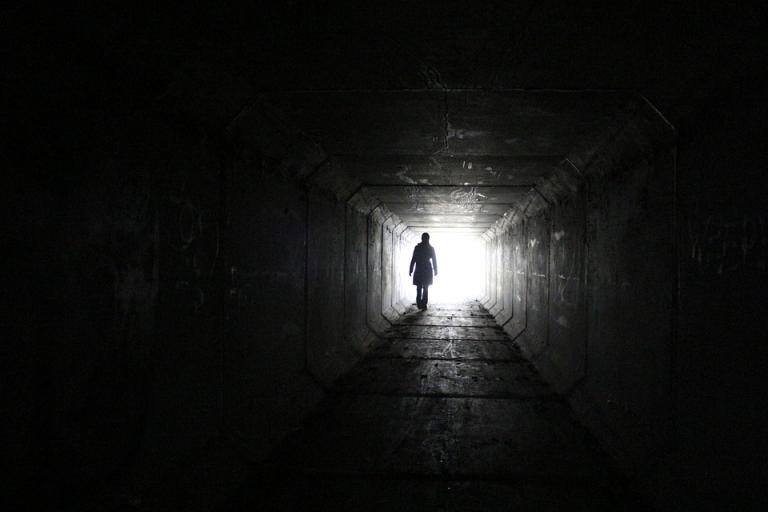

I myself, by birth and choice, long ago entered that communal dialogue with and about the Word and I want it to live, so I am become both a hearer and a speaker of the Word though my remaining days are few. I think Feuerbach, Santayana and Gray understand some of this and respect it – though they would explain it in terms far from mine. Their philosophies would leave me and my religious siblings some room to breathe, and for our different worlds to touch at some point. What more can we hope for in this age of darkness and cacophony?

image credit: pixabay.com/photos/tunnel-silhouette-mysterious-899053/