Remember back when we first went into lockdown, when we were “all in this together,” when we posted pictures of ourselves posing as famous paintings, and rattled our pots and pans in the streets to thank our essential workers? Those times feel long ago. Apparently, people assumed that a two-week lockdown would give everyone a nice breather, then we’d emerge into a bright new plague-free world. Perhaps people did not listen to the scientific experts, refused to believe them, or let themselves be swayed by politically-motivated conspiracy theories; whatever the reason, it’s a very different pandemic scene now.

Some of us live in reality. Others do not.

Anti-maskers have made flouting common sense, ethics, and health precautions a matter of valor. Those of us who care about the survival of our more vulnerable friends and family will not be able to have family gatherings for quite a while, thanks to the irresponsibility of others whose recklessness affects everyone around them. Yet somehow we are not allowed to be angry at these people – nor at those who voted for ethno-nationalism and incompetence twice in a row – because this is too “divisive.” We are supposed to look on the bright side of life, as we slide precipitously into stark dystopia.

The numbers are spiking, even more alarmingly than the experts anticipated. Lacking any real leadership on a federal level, the relative safety of a particular region is contingent both upon the strength of its local leadership, and the moral sensibilities of its populace.

The Trump contingent said “it will be gone after the election.” Please note, for posterity, how wrong they were. It is not gone. And unfortunately we have to wait for January for Trump to be gone. Biden will initiate a plan for containing the pandemic when he steps in, but will it be too late by then? How many will die, before this is over? Which friends whom we are missing now will no longer be alive to greet us, on the other side?

Remember when we were supposed to be using our quarantine creatively?

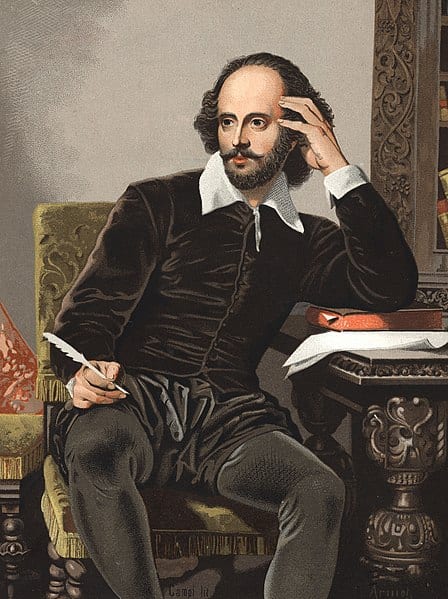

When we were reminded, cheerily, that Shakespeare wrote King Lear while the plague swept through London? Remember how, at first, we thought we’d use our lockdown time to finish off that novel or play we were working on? Then reality settled in, with all the anxiety and existential dread entailed. The massive inequalities in our society were exposed. While nurses had to sleep in basements to avoid infecting their families, and workers went months without paychecks, the wealthy had nothing worse to fear than an involuntary staycation. Taylor Swift spent her quarantine in her big haunted mansion writing songs about teen love triangles, with no relevance to the lives of working class people struggling to survive. Many of us, with no haunted mansions built by wealthy heiresses, but still with bills to pay, had no time to write or create. Others experienced creative paralysis. I know people who have been unable to write for months on end. And for many whose art depends on performance, this has been a time when they have been unable to create, and are deprived of any profits of their creation.

The other day I was reminded, again, about Shakespeare writing Lear in quarantine, and I think we missed the real point of those stories about artists producing great works in plague time. These stories should not be used to shame us into using our isolation more productively. They should serve as a reminder of the resilience of the human spirit and the role of art in survival.

Artists making art in quarantine are not doing so as a fun hobby. Edvard Munch not only quarantined, but contracted the Spanish Flu. While in recovery he documented this experience, in his Self-Portrait With the Spanish Flu. After Giovanni Boccaccio’s parents died of bubonic plague in Florence, he fled to a villa in the countryside, and wrote the Decameron.

It is a mistake to imagine these artists blithely summoning the muses while enjoying a little relaxing sit-in. It was a mistake for us to expect our own lockdown to be that way. How could we think of King Lear as the fanciful creation of a cheery soul enjoying his quiet time? These artists created work in times of loss, sorrow, rage, and uncertainty. They were not polishing up neglected manuscripts because there was nothing else to do. They created art as a mode of survival.

In Shakespeare’s case, with the theatres closed, actors out of work, managers with nothing to manage, the concept of survival was real and material, not just existential. There was a good chance that the plague would destroy his career, leaving him penniless and futureless.

As Andrew Dickson writes,

When you know this, it’s hard not to hear the echoes in Lear, arguably the bleakest tragedy Shakespeare wrote. The mood in the city must have been ghastly – deserted streets and closed shops, dogs running free, carers carrying three-foot staffs painted red so everyone else kept their distance, church bells tolling endlessly for funerals – and something similar seems to be happening in the bleached-out world of the play.

The great art produced in time of plague, war, and civil unrest is born out of suffering. This is not something anyone would seek out or want to repeat. It also is not necessarily within the artist’s control. Finding oneself silent, unable to make art in quarantine, is not a failure of creativity, because silence is also a valid response to pain.

We are not meeting this moment with moral seriousness.

Our culture of instant gratification, which pursues surface freedom over genuine liberation, does not dispose us to make art that meets the needs of dire times. In our refusal to take the pandemic seriously, refusal to quarantine, refusal to mourn, refusal to sit silently with an understanding of what’s at stake, we have closed the door to the gift of creation. Sure, any pop star with extra time on their hands can write yet another pop love song, but sometimes pop love songs aren’t going to cut it. We need Lear; we need to be able to rant and rave on a blasted heath, and ask the ultimate questions about life, death, justice, and love. We need to be honest about the fact that the questions might not be answered, even if this upsets people.

Whether silent or vocal, those of us who are sitting with these questions find ourselves in a new isolation, not simply the isolation of quarantine. What we see, and fear, others pretend is not real. “Are we the crazy ones?” we ask each other.

Ironically, while we may not be creating King Lear, we are having a Lear moment. Lear brought about his own tragic downfall through his arrogance, blindness, and irresponsibility: our national characteristics, writ large for the world to see. Where this will lead, it is hard to say: that is why we are alarmed, sometimes alarmed into silence.

The future is uncertain. But we know it will be hard. If we can make good art, it will acknowledge this. It probably will not be cheerful.

image credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:William-shakespeare-portrait-of-william-shakespeare