Let me clarify that there are two distinct ways of understanding “political correctness.” One is the expectation that one’s statements will be in line with the accepted politics of your milieu. Different circles have different accepted politics. In some circles, it might be politically correct to to refer to trans persons by their preferred pronouns. In other circles, it is politically correct – that is, satisfies the expectations of the dominant hegemony – to make a point of not doing so. A person at a conservative university who preens himself on not caving to the demands of political correctness is, in fact, being as politically correct as possible, under this understanding. Such a person is doing what he knows will earn him applause. He’s taking no risks. This form of political correctness has to do with codes, and tribes. I guess the honorability of this corresponds with the moral decency of the respective tribe.

But the other understanding of political correctness is simply of standards that allow us to co-exist politically. Civility, politeness, tolerance, manners, respect: all of these get lumped into the perhaps unfortunate moniker “political correctness.” Like the term or not, the idea is that we get along more smoothly, and more justly, as a political unit, when we treat one another according to the golden rule.

In the 90s it was fashionable, among right-wingers, to mock political correctness by emphasizing what we then perceived as extremes. Renaming garbage men – or women – as waste disposal management persons, ha ha ha.

But we forgot, in our rather puerile laughter, that garbage collectors are also persons of inestimable worth and dignity. Collecting garbage isn’t something we should mock: it’s needed work, real work, that provides a clear benefit for society. So, even if there’s something a bit pretentious and forced about “waste disposal management person” the idea behind it is that it’s better to emphasize the value of a person, and of their work, than to emphasize their vulnerabilities..

A blessed relief, really, after the bullying 80s.

Proponents of political correctness recently have simply been emphasizing that in a pluralistic society we need to practice basic courtesy, and that this often means taking the time to find out about one another: about our culture, religion, sexuality, and background. It’s rooted in the same concept of courtesy as was present in Newman’s definition of a gentleman. One wishes never, deliberately, to cause harm.

It’s ironic that the people who spent several decades trashing political correctness are now demanding civility towards themselves alone. If Milo calls for reporters to be shot, it’s just a joke, but if Sarah Huckabee Sanders is quietly asked to leave a restaurant it’s an assault on human dignity. Trump can mock a disabled reporter, but heaven help us if we mock Trump.

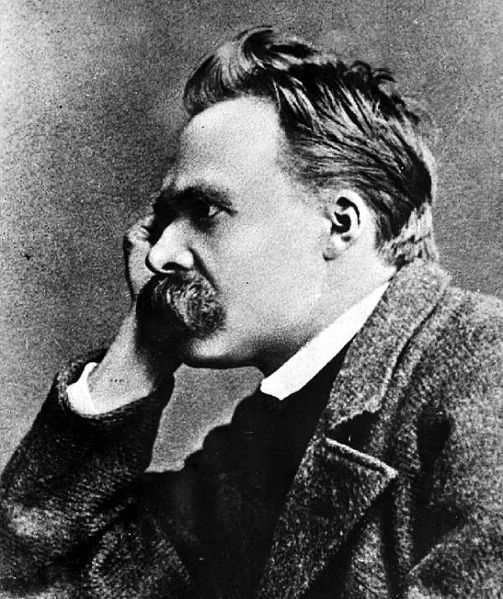

This is the classic, and rather boring, illogic of the bully – the one who can dish it out, but can’t take it. It’s rooted not in strength, but in weakness. The morally strong and courageous person shrugs off insults, but tries to avoid harming others, and rises always to the defense of the marginalized. This was what Nietzsche, for all his perception, didn’t get about the Christian charitable ethos: that it arises not from weakness and fear, but from moral fortitude – as Max Scheler eloquently argued in his work, Ressentiment.

Ressentiment, as explored by Nietzsche and further clarified by Scheler, goes beyond mere resentment or revenge. There’s a crude honesty about resentment, and a courage in revenge. Ressentiment has to do with a deep spiritual rancor against goodness itself, a rancor which blossoms and blooms in the false flowers of a topsy-turvy and nihilistic value system.

Those who feel threatened by the existence of moral or aesthetic value systems themselves retaliate by turning against them. But they don’t say “hey, I’m sick of this morality stuff; I’m going to be a hedonist.” There would be a certain swashbuckling glamour in that.

But instead, they invent an alternative value system. Ugliness becomes beauty. Pain becomes joy. Hurting others becomes virtuous. The dishonesty at the heart of ressentiment goes deeper than lying, too: people overcome by ressentiment actually believe their own fabrications.

One instance of ressentiment I see today is when white persons respond not with generous magnanimity, but with spiritual rancor, to the cries for justice from black communities. Here is a value system in which we white people no longer get to be enthroned in the center – in which we need to take a step back, even admit our wrong. Lacking the guts to do this, we respond by attacking the whole structure of justice itself, and upending it, so that the oppressor class itself becomes – in the ressentiment-laden mind – the victim.

Nietzsche mistakenly identified ressentiment as a trait exclusively of the victim class lashing back, failing to see how feeble those who occupy positions of power can often be: what we now might term “affluenza.” He also mistakenly identified ressentiment in the Christian emphasis on the cross, thanks partially to the tendency of Christians to cast our own theology in unfortunately sado-masochistic terms. In correcting Mietzsche’s error, Scheler may have run a bit too far in the opposite direction, especially in his lumping in Christian values with “knightly” values. But Nietzsche did the field of ethics an inestimable service by identifying the phenomenon of ressentiment as a source for false and nihilistic value-systems, and Scheler did our theology a service by recalling us from nihilism.

Nietzsche is misread by many thinkers, even thinkers I esteem. They misunderstand his emphasis on power as a lust for political power, when in reality it’s more spiritual or aesthetic power, vitality, life-force, that he reveres.

Nietzsche receovered from his Wagnerian phase, and went on to prefer Bizet’s Carmen, incidentally. He scorned political force, loathed boorishness, and mocked nationalism – especially the proto-Nazism of his fellow Germans. Those who think Trump is exercising anything like a Nietzschean will to power haven’t read closely enough. Obsession with power over others – bullying power – is the last resort of the weakling. The magnanimous one, the artist, the dancer – she doesn’t need to force others or inflict pain.

If he were alive today, I think Nietzsche would see the most pristine instance of ressentiment in the case of the Trumpian upending of values – and in the fundamental moral spinelessness of those who defend this. All the while claiming the privilege to bully, abuse, and attack, but crying victim whenever anyone serves them back a dose of what they’ve been giving. Those who thought they didn’t like political correctness, until they got a taste of their own poison.

image credit: https://am.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E1%88%B5%E1%8B%95%E1%88%8D:Nietzsche.jpg