Wrapping up one of the most famous cases of censorship in the history of modern western literature, James Joyce’s monumental novel Ulysses was put on trial for obscenity in the United States in 1933 – and exonerated.

Prior to this, the book had been banned since 1920 in the United States. It was publicly burned in Ireland, England, the US, and Canada. It was formally banned in England in 1929. While Ulysses was never actually banned in the native Ireland of its expat author – who wrote it while residing in Europe – neither was it offered for sale, because sellers feared a backlash.

Nevertheless, champions of literature, art, and freedom of expression had done their best to make the ground-breaking novel available to readers. Ernest Hemingway himself smuggled copies into the U.S.

The 1933 ruling, by Judge John M. Woolsey of the United States district court, stands as a landmark event in the history of the struggle of art against censorship. Central to Woolsey’s conclusion is a decision that rests on the distinction between objective content and reader reaction. An objectively obscene work “as legally defined by the Courts is: tending to stir up the sex impulses or to lead to sexually impure and lustful thoughts.” Woolsey goes on to point out that this definition “must be tested by the Court’s opinion as to its effect on a person with average sex instincts” and later “it is only with the normal person that the law is concerned.” Namely, that the content in Ulysses is not designed to elicit a sexual response in a person with normal and healthy instincts or appetites. The Courts can not answer for abnormal appetites.

What this means is that the fact of a person being aroused by a work of art can not per se be taken as evidence that the work of art is intended to arouse.

Those who have unhealthy, abnormal, perverse, or immature sexual instincts might find any number of things provocative. Furniture. A corpse. A description of a kiss. Classical art.

When a person admits to being sexually aroused by that which is not intended to sexually arouse, that person is saying far more about themselves than about the work of art.

It may simply be a matter of immature and underdeveloped instincts. There’s a stage of adolescent sexuality at which everything is a turn-on; one of the goals of education is to lead people through and beyond this immature phase, into a realm of greater objectivity and self-control in which one is capable of viewing human experience in an objective and clear-headed manner. This is necessary especially in certain lines of work. If a medical professional can’t see a naked body without falling into paroxysms of lust, or if a counselor can’t listen to a story of sexual intimacy without succumbing to titillations, they should not be in these fields.

Incidentally, a person who is still in the adolescent stage of sexuality is not yet ready to enter into mature sexual relations themselves. In order to enjoy a healthy sex life, one has to be discriminating.

There are certainly works that are pornographic, and a broad array of works specifically intended to provoke arousal. My intention here is not to discuss those works, which themselves exist across a wide spectrum, from classical erotica of both Eastern and Western cultures, to early photographic erotica, to the highly artificial, dehumanizing, and damaging pornography available at your fingertips on the internet today.

But there are other works which, though dealing with sexual or erotic subject matter, are not pornographic nor even erotica. The role of the work, the art, the language, and the narration is such that it gives the viewer a distance from which to observe and discuss. The arousal takes place within the story, but does not reach out and enlist the viewer to join in.

There have been a few times in the past when people – never my students – questioned the works I was assigning in class. A frequent objection these people made was that explicit descriptions of bodies, or of certain sex acts. left them with “feelings they didn’t want to have.”

Did these people not realize what they were disclosing to me? What they intended as an accusation of certain books actually came off as revealing far too much about themselves, about their sexual immaturity and lack of self-discipline. Especially given the fact that I had students much younger than them, capable of coolly and thoughtfully discussing the scenes, and their implications, in an academic setting.

And unlike explicit material in a work of art, which is buffered by the parameters of art, revelations about “feelings I didn’t want to have” are deeply personal and, to my mind, inappropriate, especially when told to me by a member of the opposite sex. I am perfectly comfortable reading and discussing Joyce’s descriptions of masturbation, because they are enclosed within the “safe space” of art. I am less comfortable listen to a grown man tell me about the sexual feelings he didn’t want to have. That strikes me as far more immodest and inappropriate than a sex scene in a novel.

People who are up in arms about indelicate or difficult material in literary works of art are telling the literary world very little about the works of art. But they are telling us all far more than we ever wanted to know about themselves, and their sexual issues.

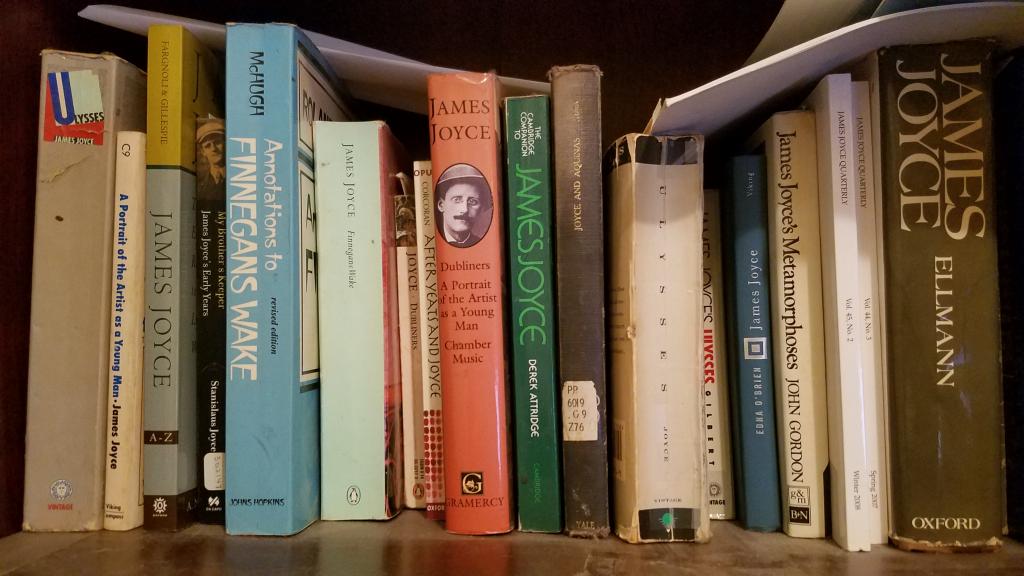

image credit: the author’s dusty bookshelf