When I was teaching Women Writers, my signature course for many years, I used to reserve one class period to talk about the history of women’s rights, since political representation is connected with the power to be heard as a literary writer as well as a policy-maker.

The first time I prepped for my lecture, I spent some time putting together an abridged timeline of women’s suffrage. I like timelines. It’s fascinating how patterns emerge, when you think you’re just putting together a collection of dates.

Obviously, there was no way I was going to account for every sovereign state in the world, but I wanted to make sure I gave credit to the first in which women won the right to vote (the Isle of Man, incidentally, at least among “modern” documented nations), and to touch on other familiar nations, across the globe.

This was when I happened upon an interesting little fact. At the time, there were only two sovereign states in the world in which women had no voting rights whatsoever, not even feeble paltry ones. One – and this will come as no surprise – was Saudi Arabia. The other? Vatican City. Since then, however, Saudi Arabia has extended limited suffrage to women citizens, leaving Vatican City as the sole state in which men and men alone have voting rights.

Only ordained men, you may hasten to respond.

Well, sort of. But as a matter of fact, at the present Synod on Young People, any lay brothers who are part of the delegation have been granted voting rights. The delegation consists of 300 men, and only 36 women, and none of the women present has been given a vote. That means, young women readers, decisions that affect you intimately, your bodies, your role in the church, your protection, your vocation, your career, your family life – will all be made without a single female voice being taken into consideration.

And “only ordained men” still means “only men.”

Asking to be heard

The historical significance of this was made vividly present to me last week, when I was privileged to be a part of the Catholic Women Speak symposium and book launch preparatory to the Synod. The book being launched, Visions and Vocations, contains a number of essays from women around the world, of all ages and backgrounds, exploring their vision for women in the church. While a prior work obligation meant I had to arrive late for the event, I was still able to participate in small group discussions, and hear women speak about their work to make a space for our voices, in every part of the globe.

Catholic Women Speak may appear to some to be a radical group, but this is, in a sense, ironic, since our only “agenda” is to help women to be heard. This means women who are advocating for women’s ordination and LGBTQ rights, yes – but it also means defending the rights of women who have no interest in these topics, and wish to be heard on other themes that are pressing for them, in personal life and culture. That this comes off as radical demonstrates just how silenced women are.

The final event I participated in, with the group, was a protest outside St. Peters, as the cardinals and bishops participating in the Synod were arriving. There is something fundamentally energizing about being there, in Rome, for any reason. For all the scandals and errors of the church, in the past and recently, there in st. Peter’s Square one is reminded that this business of being Roman Catholic is not just a niche affair (something easy to forget, when confined in conservative backwaters). One is reminded by the vastness of the space itself that the church, too, is vast, and global, and that it’s not so easy just to walk away from it, as from a weird little cult, because what happens in Catholicism has global repercussions. At a time when I was wondering, can I even stay in this church, being able to be there – and especially for the reason I was there – was the answer that I needed.

It was a peaceful protest, in which we called out the participating bishops and cardinals by name, with the repeated mantra, knock knock, who’s there? More than half the church!

Onlookers gathered, most of them supportive, or at least glad of the diversion. Reporters took photos, and a few approached some in our group to ask questions. One politely took me aside and asked what we were working for, and whether we thought our protest would make much difference? I had to admit that no, I did not think that it, on its own, would make a difference, but we have to start somewhere. “One thing we know about the church is that it’s full of surprises,” I said. “Lately, most of our surprises have been bad, but maybe it’s time for some good ones, for a change?”

Then the police showed up.

They began by telling us to leave, and then they came closer, getting up in women’s faces and shouting. BE SILENT, one of them shouted, which I found especially telling. When our group organizer – one of the youngest women present – turned to walk away from a police officer who was lecturing her, he grabbed her by the arm and yanked her back, forcibly, causing pain. Many women who hadn’t sidled away from the police confrontation had their passports taken, and it was a while before they could get them back.

I was one of those who sidled away, because I didn’t think my family would be thrilled if I told them “sorry, can’t get back, in a Roman jail!” I stood off to the side and tried to capture the scene on my phone, as best I could, though it was hard with all the crowds. Eventually they sent a whole police van, with armed officers – and finally even police on horseback. Afterwards, I joked with one of the women that we should have been on horseback ourselves.

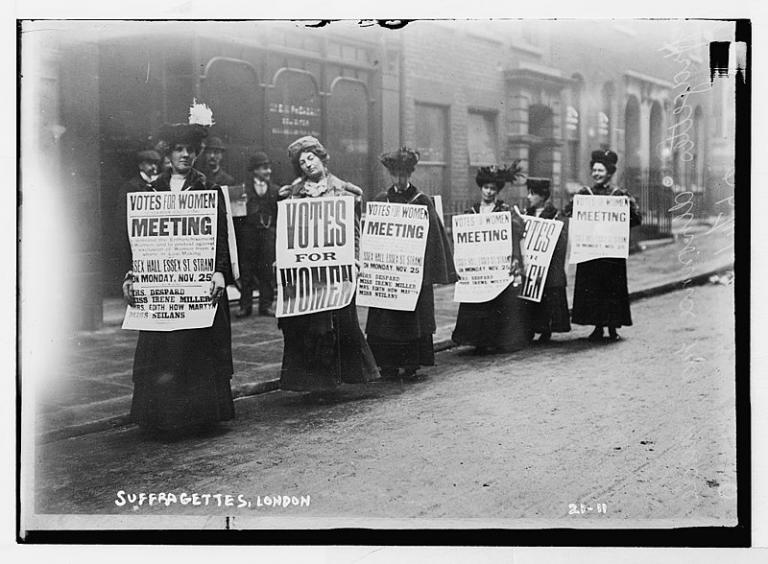

Not just because I love horses and feel braver on horseback. Also because it felt like “back then.” One hundred years ago, when women protested, and were shouted at, abused, beaten, and jailed simply for asking for the right to vote. And what we’d been asking for hadn’t been heterodox, either. We weren’t there fomenting to be ordained priests, nor even to be made deacons or cardinals (theologically acceptable though these moves might be). We were simply asking for the rights women have worked so hard to win, in all the nations of the world: the right to be heard.

Now, the thing is, the church once was where women could go to be defended, to be treated as humans and children of God instead of as possessions. The church gave women the freedom to escape from forced marriages, and religious life in the church opened doors for women to be educated, and even to rule, as they had never been able to do, in the Roman regime. And this was no accident. It was part of the entire ethos of Christianity, at the heart of the Gospel, for women to find this freedom in the church.

And so it should be still today, but it is not. Ideologues who are obsessed with defending the church’s historical deeds without regard for reality might argue to the contrary, but it simply is not true. The church has not. Repeatedly, it has failed to do as it should have done, as it – as we – were called to do. Not just as regards women, but as regards minorities, Jews, the native peoples of the Americas, the people of Africa who were enslaved by “good” white Christians. The church should have excommunicated every single slave holder, but it did not.

It should have, though. That’s what I keep coming back to. That the church according to the heart of its identity, which is the presence of Christ among us, OUGHT to be the premiere defender of the vulnerable or downtrodden, the greatest instrument of peaceful justice – and not just by accident, not just by happy fault, but because of what it was meant to be. And, throughout history, the church has often veered away – far away – from this intention, but repeatedly reform movements have risen to bring us back.

image credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Suffragettes,_London_LCCN2014680110.jpg