CONVERSION NARRATIVES

Starbuck (1866-1947) and James (1902) were pioneers in the field of Conversion studies. Both of these relied on “conversion narratives” in their studies. Later, the Oxford Handbook of Religious Conversion would include a chapter exploring conversion in terms of narrative.

A “narrative” in this sense is simply a story which has a definite beginning point, rises to a narrative climax, and then has a definite conclusion.

In terms of conversion narratives, the standard format in people’s minds is what is called a “crisis conversion.”

CRISIS CONVERSIONS

Very simply, a crisis conversion is a story wherein there is some sudden moment of inspiration wherein the individual moves from a state of pre-conversion to post-conversion. It denotes a definite moment in time wherein the conversion occurs.

This crisis conversion narrative is typified by Saul of Tarsus who, in a single experience, went from a man who hated Christians to a man who was a Christian.

This same narrative exists within most other religions, as with the sudden enlightenment of the Buddha, the burning bush speaking to Moses, and the moment when Muhammad is seized by an angel and forced to recite.

This idea of a sudden, inspirational moment of “salvation” is still very much the standard model in the Evangelical mind, which uses markers such as the “sinner’s prayer,” alter calls, and speaking in tongues to identify a new convert.

Indeed, Christian fiction and folklore often uphold the crisis conversion as the standard. Instances include such stories as Pilgrim’s Progress when the central character lays eyes on the cross and releases his burden within a moment; or the well-read autobiography of former slave trader John Newton who fell on his knees in repentance of all his evils, and subsequently penned the celebrated hymn “Amazing Grace.”

Given that we do not have access to the hearts and minds of converts, there is no way to verify any moment in time when the individual goes from not religious to religious. However, in most models used in the field of conversion studies, the process of conversion is just that: a process.

Nevertheless, in the conversion narratives I have studied of Atheists who have converted to Christianity, there very much remains that moment of inspiration (although not necessarily the moment of “salvation”).

ATHEIST CONVERSION STORIES

- Warner Wallace tells of the night he lay awake tossing and turning as he went over and over all of the things he had been analyzing in the Gospels. Finally, he woke his wife and told her he thought it was all true.

- Francis Collins speaks of the moment he rounded the corner on a mountain walk, and saw the astounding crystalline display of a frozen waterfall rising above him. This became a profoundly spiritual experience for him and remains the central climax in his conversion narrative.

- For Peter Hitchens, that central point involves the viewing of medieval art depicting lost souls cast into hell. Although an unbeliever, Peter was somehow struck by the notion that this is the fate he actually deserved.

- C.S. Lewis speaks of a night of profound struggle wherein the proverbial “hounds of heaven” were nipping at his heals, and he was forced by intellect and spirit to concede that there was, indeed, a God in heaven, describing himself as being dragged wholly unwillingly into conversion.

- Tyler Vela’s conversion narrative includes as a defining feature this moment of dawning delight after he becomes a Christian: he listens to Christmas Carols he has heard all his life, and suddenly understands what the words of the carols mean.

The moments described above do not represent the entirety of these individuals’ conversion experiences. And with the possible exception of Lewis, they do not even represent the moment these people decided they were Christians. They represent mere dramatic instances within a much larger conversion narrative: where the rising action climaxes within the story.

Nevertheless, it is these dramatic incidents around which the narrative rotates, and perhaps merely because of the drama involved, they become the defining features that are repeated with every retelling of the conversion story.

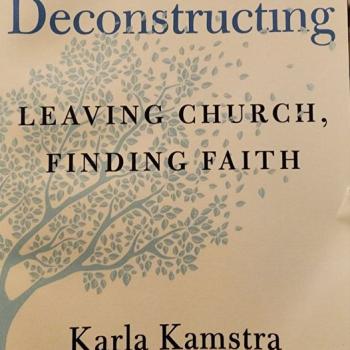

DECONVERSION NARRATIVES

The question now becomes, can a deconversion experience be viewed through the same narrative lens as a conversion experience?

If actual crisis conversions are relatively rare, there is practically no such thing as a crisis deconversion. However, so long as one can say that a deconversion story can be framed with a beginning/middle/end format, then one can still construct a narrative for the incident.

While beginnings and endings are somewhat arbitrary and may move about depending on the age and experience of the teller, it is that central point with which I concern myself.

Meaning, do most deconversion narratives contain some defining moment around which they revolve, and which remains a fixed feature of the story through multiple re-tellings?

In the model I have developed for deconversions, the “narrative climax” is usually seen on one of four possible stages:

- Early Trauma – Early Trauma is not a feature common to all deconversion narratives. But it can be seen occasionally as one does a broad survey of these stories. Early Trauma can be anything from abuse at the hands of a church person to trauma brought on through some teaching or ideology (rapture anxiety being a common culprit).

When the trauma frames the person’s view of what religion is, it can be the driving force behind the narrative.

- Stressor – The stressor stage of the deconversion process is defined by any sort of sudden or significant change from the status quo. Stressors could be anything from the death of a loved one, the betrayal of a friend, or a move away from home (especially when the home was the only environment with which the person was familiar). In a deconversion narrative, the stressor may be an incidental feature of the story (often leaving the home for college falls into this category), or it could be central to the story, such as Hannah Timpson’s tale of the death of a well-loved church leader.

- Trigger – The most likely suspect for the narrative climax would be the “trigger event” present in every deconversion story. This is usually as close as a story gets to a “moment of inspiration.” The trigger event represents a specific question that gives the individual “permission” to begin questioning or deconstructing their faith. By way of random example, Rachael Slick’s trigger was the question “If God is unchanging, how have the moral rules in the Bible shifted so drastically from Old to New Testament?” Bart Ehrman’s trigger was a theology professor who suggested that a Gospel author might have made a mistake. Cassidy McGillicuddy’s trigger was intercessory prayer and how pointless and ineffective it seemed.

- Post-Deconversion Crisis – While one never sees a “crisis” deconversion, one sometimes sees a “post-deconversion crisis” (PDC).

What this means specifically is that after the person comes to realize that they no longer believe, they reach a point of crisis: what is their identity now, as an unbeliever? What will happen to their community of friends and family now that they no longer believe?

PDC’s are by no means a universal feature of the deconversion narrative. Frequently by the time a person decides they no longer believe, they have a sense of relief to be out from under the pressures and restrictions of that religion. Where one sees PDC the most is when the person was heavily involved in the ministry – frequently when the ministry is also their career.

Given that the ministry is their day-job, their personal identity, and their public identity, the loss of this tends to mark a dramatic shift for which they are not always prepared. This is typified by Pentecostal minister Jerry DeWitt who includes a very vivid description of his PDC when telling his “exitmony.”

DECONVERSION AS A NARRATIVE

As a deconvert attempts to make sense of their experience, their narrative typically begins with where they are rather than where they used to be.

Once the person describes their current situation, attitudes, and beliefs, the narrator begins to talk about their past in light of their current perspective.

At this point, the story tends to focus less on them, and more on the environment and influences which surrounded them.

After the narrator sets the scene, so to speak, they develop a timeline which tends to focus specifically on those inconsistencies and morally suspect beliefs and practices that typified their religious life.

Given that the person telling the story is aware throughout the narration that something is deeply wrong with the environment and beliefs – something that they, as a character in the story – do not know, the story then becomes a sort of “reverse enlightenment.” The story isn’t about a path that leads to truth, but rather a tale of discovering error.

So the narrative structure is typically this:

- Current beliefs and perspectives

- Description of religious people and environment

- Anecdotes to illustrate the nature of the religious background

- After the anecdotal portion, the narrative assumes a more temporal quality, wherein the narrative begins to focus around their “deconversion career.” They will typically begin with some kind of stressor or change of status quo. At this point, the trigger occurs, and after that, a period of quest and discovery at the end of which, they are no longer a believer.

- After the “deconversion career” is described, the narrative returns to their current situation, re-framed in light of the background and events they just described.

When a believer gives their “testimony,” it is almost always done to the end of showing how effective and important their beliefs have been in their life. In this respect, a testimony is less autobiography, and more an assessment of the belief system itself. By contrast, an “exitmony” always tends toward a critical assessment of the belief system in terms of its flaws and failings – especially as it has failed the narrator.