In a previous article, I reviewed research which suggested that, despite the reputation Christians have for being anti-intellectual and unsophisticated, on average, they actually are every bit as sophisticated as atheists in their thinking – if not even slightly more so.

This research used a system called “Integrative Complexity Analysis.” This form of analysis takes a text or speech and analyzes it for multiple approaches to the subject at hand: the presence of nuanced rather than black-and-white thinking, the ability to take other people’s perspective, and other markers of complex thinking. An example given by one of the researchers is the subject of broccoli. A text which simply supplies the author’s opinion of the taste of broccoli is relatively un-complex. However, if the author were to talk about the texture as well as the taste, talk about why other people appreciate broccoli, discuss the botanical aspects and significance of broccoli, etc., the person has taken a complex approach to the subject.

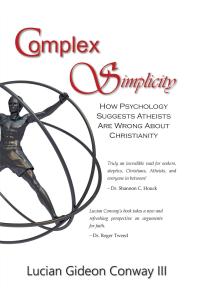

The research I cited for that article occurred in 2018. A year prior to the publication of that research, one of the scientists involved in the research, Lucian Gideon Conway III, published a book titled Complex Simplicity: How Psychology Suggest Atheists are Wrong About Christianity. As the subtitle suggests, the author is using his background in psychology to defend Christianity as, at least, a force for social good; and at best: entirely true.

To say that this book was research in the strictest terms might be a bit of an overstatement. Despite his background in psychology and a number of excellent peer-reviewed studies under his belt, the book would better be described as a work of Christian Apologetics than a book of rigorous scientific work. This is not to say that the book did not use actual psychological research or theory in the cases it made, but rather that it was written in a distinctly conversational manner so as to appeal to a general audience rather than highbrows or intellectual elites.

In fact, Conway is legitimately funny at places in the book, and overall I would describe the book as a pleasant read. However, given that it is a case against atheism, I imagine that any reader invested in atheism would find it irritating for that reason. Conway is not antagonistic or even teasing in his approach to atheism, and appears to give atheists respect in his writing, so perhaps it might not be as needling as it might otherwise have been on those accounts.

The case Conway makes in this book is built primarily around his own experiences and anecdotes, with theory and research sprinkled in where appropriate. He appears to be attempting to make a friendly and conversational case for Christianity rather than a hyper-intellectual case. This is understandable insofar as he is trying to reach the broadest possible audience, but the book would probably not pass muster with atheist counterapologists trying to poke holes in the case for Christianity at a scholarly level.

Conway’s Case

Conway begins his book by suggesting that Christianity, quite simply… works. That is to say that, taken in its broadest form, Christianity supplies a foundation which allows for human flourishing, progress, and supplies the emotional and intellectual needs humans have. It is not my intent here to supply the details of Conway’s case, but he provides a detailed argument for how Christianity is sufficient for the emotional and intellectual needs humans have in a way that atheism just isn’t.

From there he provides the foundational data for the psychology of belief. One notable argument he makes is that both open-mindedness and close-mindedness are important. The former because it helps a person to learn and to grow and the latter because it places boundaries against which acceptable and inacceptable ideas may be judged. Elsewhere this has been described as the “paradox of tolerance,” wherein if one is tolerant of any and every idea or behavior, some very dangerous and damaging ideas and behaviors may sneak in the back door.

Presumably, Conway would argue that open-mindedness would allow a person to identify those things about which he or she should be close-minded.

Next Conway talks about epistemology, citing two types of epistemology: authority (accepting things to be true on the authority of someone else) and investigation (finding out what is true or isn’t by way of personal investigation). Conway notes that not all religious beliefs are solely reliant on authority (demonstrating ways in which this is true) and not all scientific beliefs are the product of investigation (again, he provides examples).

Following his essays on epistemology, Conway tackles the topic of boundaries versus freedom – or the question of “why does the caged bird sing?” Much like the open mind/close mind question, Conway argues that establishing appropriate boundaries does not limit freedom, it simply establishes the landscape in which the freedom may be practiced. Boundaries are not always cages, sometimes they are guardrails. Since religions in general include boundaries of safety in a way that atheism does not, it becomes a matter of selecting which religiously established boundaries are most secure while allowing for maximum freedom. It is in this section that Conway also argues that religion, properly practiced, makes people happy by giving them the best combination of security and freedom.

In reference to other research I have done, one might argue against Conway that religion is too restrictive and domineering, setting boundaries that privilege certain religious members while oppressing others. This is, perhaps, why Conway provides the caveat that this only works when properly practiced. However, my suggestion is that the reader examine Conway’s arguments as he provides them in the book to determine whether his system works or does not.

Conway goes on to argue that Christianity provides a metanarrative – a storytelling framework that makes sense of life and gives purpose and identity to the liver – in a way that atheism does not. Here, Conway pulls from the reasoning of the Chesterton’s and the Lewis’s of the literary world to support his case; arguing as Chesterton did that fairy stories are essential to living a fulfilling life in a way that the cold, soulless sterility of science is not.

Conway goes on to suggest that the Christian belief in things like eternal life and the power of prayer do not, as some atheists suggest, prevent them from engaging in the hard work of fixing problems or doing work in the here and now (the “thoughts and prayers” versus legislation problem with which so many readers may be aware), but rather that the presence of prayer and eternal hope simply gives Christians the courage and strength necessary to throw their full strength into engaging in the immediate work. Or put differently, it is not a zero-sum game. It is not “thoughts and prayers” or legislation, but rather a both/and.

Other arguments tackled by Conway are that Christianity provides further opportunities for both/ands rather than either/ors insofar as it allows a person to look at the physical world with objective analysis while still having the intimacy that comes with a rational Creator. He argues that Christian community allows a person to maximize both personal individuality and group belonging, and finally, he argues that Christianity serves as a sort of lid to the puzzle box containing the whole picture as we sort the individual pieces to put the puzzle together.

How is the Book?

Conway is a talented and engaging writer, making the book both easy and enjoyable to read. The book was written at the tail end of the New Atheist movement when they were still a very real presence in the online and publishing spaces, and just prior to the current Deconstruction Movement. The book ought to be read in this context. It is not what I would consider to be a sound rebuttal of the New Atheism of the time, especially given that it does not tackle the aggressively intellectual arguments of the most visible speakers of the time (although he does start each segment of the book with a direct quote from a reputable atheist source to frame the objection he is tackling). The book was probably mostly directed at a Christian audience having to cope with atheist assaults on their beliefs and shoring up their comfort and security in their religion. The subject matter and arguments have not lost any internal validity in the intervening years, but the cultural conditions have changed substantially, and if written in the current day, he would be forced to tackle many more emotional and cultural objections in order to defend Christianity against the objections of the Deconstructionists.

It is worth noting, however, that Conway’s research has continued to keep pace with cultural concerns. Most of his much more recent research has veered away from the atheist-versus-Christian debates of the 2010s and is now directed at doing Integrative Complexity Analyses on the more left-versus-right dichotomy which has emerged in the wake of the Trump presidency, COVID pandemic, BLM riots, and so many other cultural milestones bringing us to the point in which we currently find ourselves (many of these specific controversies are examined in his more current research). This book is worth a glance, at least, but keeping up with Conway’s research is a much better way of understanding the rapidly progressing cultural shifts of current day.