Testing Thought Complexity

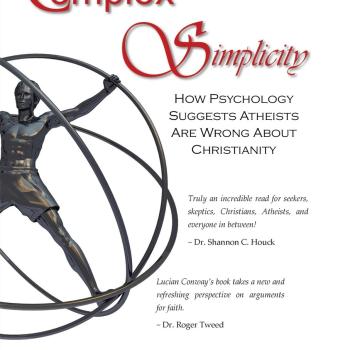

It’s a fairly common trope: religious people are knuckle-dragging uneducated troglodytes more obsessed with conspiracy theories than with actual education, and elevating dogma over science. In 2018, researchers Shannon, Lucian, Kimberly, Alex, and Joeann decided to put this trope to the test.

But how does one test the complexity of a person’s thinking, much less an entire category of people? In the case of Shannon et al, they ran what they called an “Integrative Complexity Analysis” on the words and writings of religious people and irreligious people. This analysis was able to take transcriptions of the people’s words (gathered from writings or talks) and run them through a computer analysis to test things like the complexity of vocabulary, the internal structure of the person’s word usage, and other markers which indicate a complex and considered way of forming and communicating thoughts. The researchers used a tool known as an Integrative Complexity scale (IC) in order to measure the degree of complexity in a person’s thinking on a spectrum ranging from black-and-white thinking on the one end, to nuanced thinking which considers and integrates a variety of ideas and perspectives on the other.

Gathering the Information

Where did these researchers go in order to gather a good sample of the words and writings of religious and irreligious people? The researchers actually went to three different sources:

The first of these was famous historical writers and orators speaking either for or against religion. For example, atheist Robert Blatchford’s book God and my Neighbor (Blatchford, 1919) and Christian G. K. Chesterton’s book Orthodoxy (Chesterton, 1959) were selected for comparison as representative of the early 20th century (these two individuals were direct ideological opponents, and the books selected were part of an ongoing dialogue between the two).

The second source gathered thousands of essays written between 2006 and 2008 obtained from “This I Believe” which is an international organization devoted to the writing and sharing of essays about people’s core values (Shannon et al, 2018, p. 6). Taking the tens of thousands of essays, the researchers divided them into those which talked about religious values and those which did not.

The final, and perhaps most ingenious, test involved taking samples of writing from a notable convert from atheism to Christianity, C.S. Lewis, and evaluating the complexity of his thoughts before and then after his conversion.

Results

Each test looked at a variety of thought patterns which included written communication, spoken communication, elaborative complexity, and dialectical complexity. Across the different metrics measured, atheists outscored Christians in some metrics and Christians outscored atheists on others. However, once the numbers were crunched, Christians significantly outpaced atheists in overall complexity. The authors were cautions enough to not infer a superiority in Christian thought or communication, but results were significant enough as to dispel the stereotype that Christians were inferior. At least, in this instance, for notable speakers and writers across the last ten decades.

The second test did not include spoken communication and measured the use of religious language in writing. Significantly, the use of religious language was seen as complexity-generating such that the use of more religious language increased complexity of thought compared against the use of less religious language. This was consistent across the metrics and the level of complexity was almost identical across elaborative and dialectical thinking. When combined with the evidence from the first study, this increases confidence that religion does not reduce complexity of thinking. The final test asks the question, “is it possible that religious thinking increases complexity of thinking?”

The last study compared the writings of C.S. Lewis prior to conversion with those following conversion. On the IC scale, the complexity of thought demonstrated in his writing increased by 0.48% (Shannon et al, 2018, p. 7).

Of course, the researches had to ask themselves the question, was Lewis writing with more complexity because he was now writing on religious subjects? To answer this question, they compared all of his writing, religious and non-religious, before and after his conversion. Lewis’ complexity rated as significantly higher across the board for both religious and non-religious topics in dialectical and elaborative domains.

In the final analysis, the researchers were careful to note that it would be an overstep to suggest that religion makes one more complex in thinking, noting the areas in which atheism had succeeded over religion in certain domains of complexity. However, it was evident that religion did not seem to significantly diminish, and may have even improved complexity of thinking in certain domains.

In the introduction to the research, the researchers did not state that they were attempting to prove or disprove the notion that religious people were less complex and more dogmatic thinkers. Instead, they noted that all previous research involved interviewing people on their thoughts, rather than doing an analysis on how they thought independent of self-reports.

The Outcome

Religion and irreligion are not strong determiners of complexity in thinking. This seems like a modest assertion, one that is consistent with the results of this study, and does not directly contradict other studies about the educational or intellectual success of atheists relative to Christians. The most creative thing done by these researchers is to measure the pre-conversion versus post-conversion complexity of thought in C.S. Lewis. I would personally like to see a similar study done in the opposite direction. How does the IC of a person change when that person deconverts?

One possible explanation for the complexity of language use among religious versus irreligious people is that religion provides access to a wider range of language and tradition from which to draw. For instance, an atheist is probably going to avoid drawing illustrations or lexical features from the history of religious thought or texts, whereas a religious person has permission to do so, and also to draw from non-religious sources. It may be the variety of language available to the religious person which partly accounts for the complexity of their usage.

References

Shannon, C. H., Lucian, G. C., Kimberly, P., Alex, L., & Joeann, M. S. (2018). An integrative complexity analysis of religious and irreligious thinking. Sage Open, (2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018796302

Daws, R. E., Hampshire A. (2017). The Negative Relationship between Reasoning and Religiosity Is Underpinned by a Bias for Intuitive Responses Specifically When Intuition and Logic Are in Conflict. Frontiers in Psychology, (2017).

https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02191

Frazer, S., El-Shafei, A., Gill, A.M. (2020). Reality Check: Being Nonreligious in America. American Atheists, (2020).

Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. (2019). In U.S., Decline of Christianity Continues at Rapid Pace. [online] Available at: <https://www.pewforum.org/2019/10/17/in-u-s-decline-of-christianity-continues-at-rapid-pace/> [Accessed 22 February 2021].