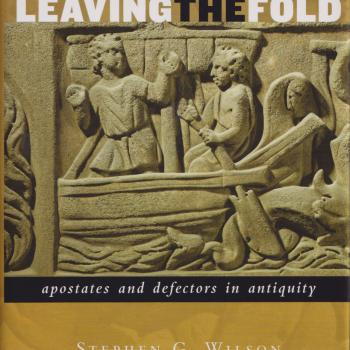

In 2009, during the height of the “New Atheism” trend, but a comfortable distance prior to the “Deconstruction” trend, researcher Raoul J. Adams noticed that what he called “apostacy” seemed to be coming primarily from Fundamentalism. Whereas the term “Fundamentalist” has gradually been replaced by the word “Evangelical,” culturally the same stigma applies: Right Wing politics loosely disguised in the garb of religion.

In 2020 the American Atheists published a massive survey it had conducted on the state of atheism in America. The paper was self-funded, self-researched, and self-published, and consequently had no academic credentials attached to it. What use, then, could the paper serve? In the body of the paper itself, the American Atheists explained that the paper was created for the purposes of political activism.

According to the paper, atheists were overwhelmingly Left leaning in their politics. Interestingly, the large majority of the atheists surveyed reported coming from a Right-wing religious background before defecting to the atheist Left.

In my personal case-studies this has been almost universally true: the subjects came from Right Wing religious origins but exited to a very Left-Wing Atheism.

Which Causes Which?

When one notices such consistent trends, one immediately wonders, “Does the person’s political change cause him or her to leave religion, or does the person’s loss of religion cause a change in political affiliation?” Researcher Vassilis Saroglou (2020) explored a similar question by asking “do the values of deconverts more resemble their irreligious peers, or do their values reflect the religious values they grew up with?” In other words, when a person moves from Christianity to atheism, do they behave more like a Christian or more like an atheist?

Saroglou’s research had the values of the deconvert sitting somewhere between a socialized Christian and a socialized non-Christian, but the most important information his research offers is the difference in values between people raised as believers and people raised as unbelievers. Succinctly, Christians tend to value security, conformity, tradition, and benevolence more highly, whereas non-Christians tend to value universalism (the idea that all should be accepted and included), self-direction, stimulation, power, and achievement more highly.

This more or less summarizes the essential difference in values which separates both religious from irreligious, but also the political Right from the political Left.

Theological Drift

Bart Ehrman is a man renown for many things. Among them is the primacy he holds as a Bible scholar, but this is second only to his somewhat infamous move from a self-described Fundamentalist Christian to his current stance of Agnostic Atheism.

Ehrman’s journey began as a seminary student when he discovered what appeared to be a historical problem in the Gospel of Mark. As he struggled to rectify the problem, his professor casually suggested that perhaps Mark had just gotten things wrong.

As a Fundamentalist, the idea that a Gospel writer might insert an error into the text was mind-blowing and earth-shaking. Ehrman’s response to this revelation was not to simply deconvert on the spot, but rather he took a cautious step in a Leftward direction. This allowed the befuddled youth to adopt a theology which says that errors might occur in the text, but otherwise, Christianity is still basically true.

Having adopted a less restrictive stance on Biblical inerrancy, Ehrman was forced to confront other theological issues this new position raised, and he continued to drift leftward theologically.

This is, of course, a natural direction to move insofar as Fundamentalism demands high levels of certainty and rigid constrictions on one’s theological categories, and relaxing those demands necessarily moves one in a more permissive direction with ideological freedom to seek refuge in metaphor and self-expression. Or, as Saroglou would have it: universalism, self-direction, stimulation, personal empowerment, and achievement.

The final blow to Ehrman’s faith came in his inability to reconcile the idea of a good and loving God with the suffering in the world.

Ehrman stands as a primary example of theological leftward drift. Next let’s examine a man whose journey demonstrates a more political form of leftward drift.

Political Drift

Ryan Bell grew up in the Seventh Day Adventist church. The SDA have a number of doctrines unique to their denomination, however among these numbers a very strict code of conduct for members – high levels of modesty for women, and a certain kind of asceticism for all members (no alcohol, nicotine, gambling, and a number of other forbidden recreational activities).

Upon taking his first post as an SDA pastor, Bell was quickly confronted with a church full of women wearing makeup and jewelry, and men taking smoke breaks in the back. He was forced into a dilemma: either discipline his church as he had been taught, or relax the church’s policies a bit. Bell chose the latter.

As Bell continued to teach and migrate between churches, his standards drifted further and further away from the SDA code, as did his theology. SDA tends to be fairly exclusive of people outside of its denomination, and Bell could not abide the idea of excluding others. So he opened up membership and teaching to non-standard individuals such as women and LGBTQ members.

Further, Bell focused less and less on preaching the SDA theology, and began to focus his church on community outreaches and events to benefit those outside of the church.

After a few years of this, Bell was removed from leadership by the SDA authority, and found himself outside the church entirely. Nevertheless, Bell continued the good fight and began to work with Humanist organizations to continue his outreached to the oppressed and marginalized.

One day it occurred to Bell that he was working shoulder-to-shoulder with self-described atheists, and that they shared the same goals and passions. What difference, he asked, did his belief in God make?

After about a year of asking this question, Bell eventually came to the conclusion that belief in God made no difference, and declared himself an atheist.

A Leapfrog Process

As seen in the previous examples, Leftward Drift occurs in stages that go something like this:

- A tension, conflict, or problem arises with one’s religious or political beliefs.

- One takes a step in a more permissive or less restrictive direction to relax the tension.

- One’s new position causes further conflict with one’s original religious ideas.

- One takes a further step Left to relax the new tension

- The new position continues to raise new problems with religion.

- This continues until one exits religion entirely.

It would be, perhaps, a bit reductionist to say that “Leftward Drift” categorizes or describes each instance of deconversion, however it does seem to be present to some degree or another in each instance that deconversion occurs.

The unique thing about Leftward Drift is that it would never work in reverse. If one were to discover that one’s position is too relaxed or free from restrictions, a step in the more restrictive direction may resolve this conflict, but it would be unlikely to raise further problems with one’s original ideas.

Heavily restrictive theology has the virtue of security and self-congratulation when one feels one is doing things right and everyone else is less holy than thou. It is this security and self-congratulation which might make restrictive theology attractive. But Leftward Drift is reactionary. It constantly looks back at where one began the journey, and continues to distance itself from those original beliefs and behaviors. And with each step, that original kernel of religion becomes less and less attractive.