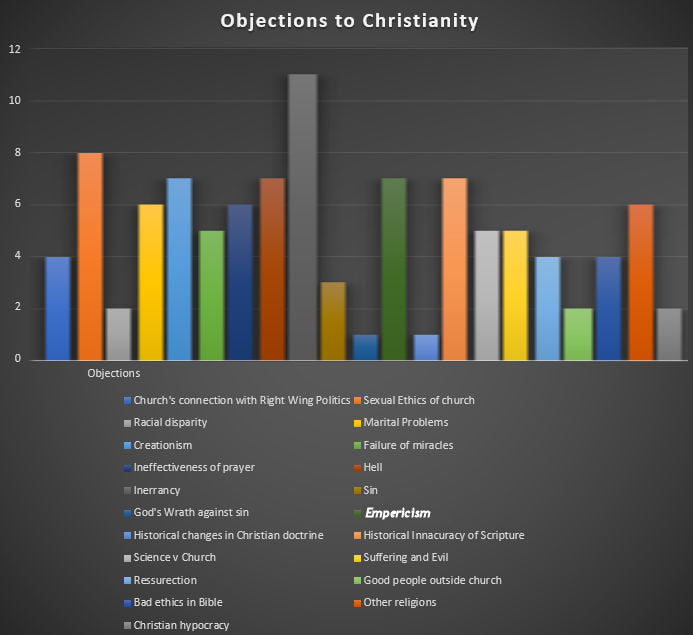

Seen in this article is a graph I created while engaged in my case study research on deconversion. This study involved gathering autobiographical stories told by people who had once been avowedly Christian, but now identified quite publicly as atheists.

The oldest of these was the late Joseph McCabe who died in 1955. At the time during which McCabe lived, finding autobiographical details of deconversion was difficult, and the person would have had to be a very visible public figure with a platform. McCabe wrote 250 books and toured the world giving lectures, and so was a visible enough figure to yield such data.

In the modern era, autobiographical data on deconversion can be had on practically anyone due to the internet and social media. I focused my efforts on those individuals who clearly identified themselves as atheists, clearly stated that they used to be Christian, and gave an explicit account of how they went from one identity to the other.

Of the many items of interest in these accounts were the specific objections the people involved had to their Christian faith. I was most interested in the objections they said occurred to them while they were still believers. A person who identifies as an atheist will likely object to most if not all aspects of Christian belief and practice, but the problems they had while they were still believers might inform me on what contributed to their disbelief.

See the chart below

Overlapping Categories

As one examines the chart in this article, one may see what appear to be overlaps. For instance, “sin” is in a separate category from “God’s wrath against sin.” “Historical inaccuracies within the Bible” is in a separate category from “Inerrancy.” Why were these objections not simply lumped together into a single unit?

The way in which these data were coded was largely based on the language used in the testimonies given by these deconverts. Objections are reactionary, and the way in which the individuals react says a great deal about the expectations placed upon them by their religious environments in comparison to their lived experiences.

Examples

To take the examples given, an objection to “sin” differentiates itself from an objection to “God’s wrath against sin” in this way:

God’s wrath against sin is an objection related to God and his specific behavior. Why would God, for instance, drown the entire world in a flood as a response to sin rather than to simply forgive that sin.

As an objection to sin itself, consider the testimony of deconvert Maggie Sergent:

“So I’m teaching about sin, and a little girl raises her hand, and says ‘what is sin?’

“And I started bawling then and there, because I felt like I could not teach a kid that they were less than perfect. That there was sin in the world, and that separated them from God, and that sin existed, and I realized in that exact moment that I didn’t believe in sin, and I wasn’t going to teach this little girl that sin existed.”

What matters in these instances is the language being used by the person providing the narrative. The specific objections these individuals outright state within their autobiographies says a lot about what was causing the cognitive dissonance which contributed to the eventual deconversion. Had this person sat down and thought things through systematically, the objection to sin would likely be consistent with an objection to hell, but hell was not in her mind when she began to break down and sob. Sin was. Plenty of these deconversion stories do prominently mention hell as a primary objection, but as a researcher attempting to understand the experience of deconversion from the internal perspective of the person having that experience (called “phenomenology”) what matters is the concept playing through the person’s mind at the time.

A more intellectually robust example would be the difference between objections to the inerrancy of the Bible versus objections to the resurrection. In my research, people who came from church environments which insisted that either the Bible was entirely without error, or Christianity was untrue would understandably find errors within the Bible to be evidence of the falsehood of Christianity. Because this is what their religious environment told them.

On the other hand, there were others who might allow for errors in the Bible, but held the sensible notion that if Jesus did not rise from the dead, Christianity was untrue. When this latter category of people encountered evidence that the resurrection did not happen, it was not the inerrancy, but rather the lack of a resurrection which constituted reason to exit their Christian beliefs.

A perfect example of how this plays out in the mind of the believer struggling with her belief can be found in the words of the ex-Christian blogger Cassidy McGillicuddy:

“I’d already encountered–and discarded–belief in literal Creationism. My church officially held that as a doctrine, but even my then-husband Biff and I knew better than to buy into that belief. I knew people believed it, and I was uncomfortable about that belief even as I preached to my various evangelism prospects about the Bible being literally and inerrantly true. I compartmentalized those two beliefs to keep them from jarring, but when I deconverted I had to set them both together for the first time–and saw for the first time how totally crazy it was that I had totally believed both of these two contradictory things.”

Here, McGillicuddy describes the process of “compartmentalizing” objections and beliefs, wherein one thing (Creationism) became so unbelievable that it was discarded, but a contradictory idea (inerrancy) was maintained in tension.

This is why when I, as a researcher, hear a person raise a specific objection (“Why did God change his standards from Old Testament in the New Testament?”), I need to avoid placing it in too broad a category when I tally it. When the potential deconvert raises an objection, it is that very specific question, and not all of the associated consequences of that objection, which is causing the dissonance which contributes to the deconversion process.

My interest as a researcher is to discover the very specific kinds of questions which refuse to be compartmentalized or cannot be comfortably held in tension with similar problems, and thus force the person into the process of re-thinking the entire belief system rather than shrugging the question off and going about his or her business as usual.

This is why language matters and why one cannot be too presumptuous when categorizing objections, if one’s goal is to understand the deconversion process.