The Teenage Exodus

It is an established fact that the teenage years are a time when many life changes are liable to occur. Early in conversion research, scholars noted that most religious conversions appeared to happen while the convert was an adolescent, and the same is true with deconversions. The mass exodus happening in churches around the world is largely happening with people in their adolescent years.

Surprisingly, however, very little of the early work on deconversion aimed its lens at teenagers. Most of the deconverts under investigation were at the very least young adults. This oversight has been filled in within the last two years, with numerous studies being directed specifically at the high school crowd.

Two of these studies have already been discussed within the column, both of which indicated that children with strong attachments and relationships to their religious parents and peers tend to be less likely to deconvert during adolescence (Hendricks, et al., 2023; Puchalska-Wasyl, 2022a). Complimentary to this finding, a recent study asked the question: do teenagers become less religious prior to deconversion? Do they read the Bible less, worship less, pray less, and then deconvert (Hardy, et al., 2022)?

Declines in Religious Participation

This would certainly make sense if deconversion was a gradual process. However, under behavioral theory, it is just as likely that religious practices would increase prior to deconversion in what is known as an “extinction burst,” meaning that the person tries harder to get a result before giving up. Or, alternately, conversion might be a “crisis event,” meaning that it happens suddenly with no visible warning.

Whatever the case, it was a question worth examining, and the researchers dug in. In order to investigate the question, they measured the religious practices of over 1100 teenagers across a four-year period. There was no guarantee that any of them would exit the faith, but with the high rates of attrition, and with a sample that large, it was a pretty good bet that at least some of them would.

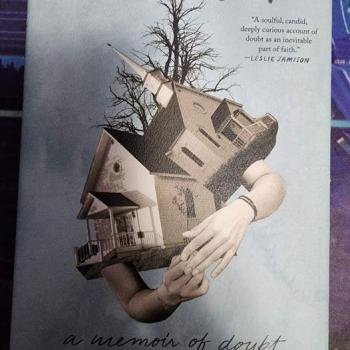

Measured once a year for four years, the researchers looked at the level of doubt being experienced by the teens, whether the participant still thought of him or herself as Christian, and the rates at which these teens did religious things (church attendance, prayer, scripture study, and spirituality).

The findings were in some ways predictable, but also surprising in some ways. One of the more surprising findings is that religious practices tended to go down over time whether or not the person ended up deconverting. It seems that teens just get less religious in general as they mature.

But unlike their religious practices, the level of doubt being experienced by the participants in the first year remained steady across all four years. Those who were doubtful at the beginning did not reduce in doubt, and those who were more certain did not become less certain.

As might be expected, then, those who had higher levels of doubt in the first year of the study were very likely to have left by the fourth year. In practice, this means that it is possible to predict whether or not a youth will exit the church by how doubtful they are early on. But this also compliments the study mentioned earlier which suggested that strong religious connections serve as a buffer against deconversion.

Not at all surprising, though, was the chief finding: yes, religious practice and participation did decline more steeply prior to deconversion.

But what, you might ask, about family relationships? We know from other studies that adults tend to be alienated by religious family and friends after deconversion, but is the same true of youths? For this answer we turn to another study, titled “Does leaving faith mean leaving family?” (Hendricks, et al., 2023)

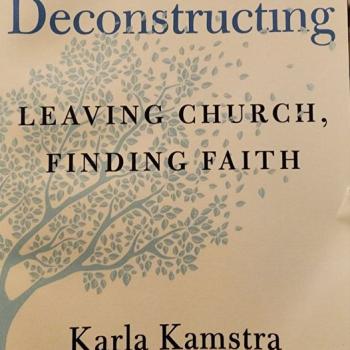

Leaving Religion, Leaving Family?

This was a three-year study which set its sights on youths who underwent any religious change at all. Perhaps this means leaving religion entirely, but it could also mean switching from Protestant to Catholic or from Christianity to Buddhism.

Again, the results were fairly predictable: teenagers who made faith changes but still held to some religious views were able with little difficulty to keep amicable relationships with their parents. However, leaving religion entirely did put a strain on family relationships just as it has done in surveys of adults.

The Turmoil of Youth

Because adolescence is a period of identity formation, emotional turmoil, and a time when individuals tend to compare themselves to their peers and encourage or discourage themselves internally, a number of studies rightly aimed their sights on the social and internal turmoil of teenage youths.

One such study found that the things about deconversion which hit youths the hardest in their emotions included withdrawal from the religious community and losing their religious participation as well as their religious beliefs. Like many studies before it, this study also found that the religiousness of the parents may serve as a preventative factor against deconversion (Puchalska-Wasyl, et al., 2022a).

Several other studies found that when a teenager finds herself constantly comparing herself to her peers, she experiences higher levels of social anxiety. Anxiety leads to self-consciousness, and when this self-consciousness is internalized (rather than openly expressed), it is more likely to result in deconversion (Zarzycka et al, 2023).

Spotting Hypocrisy

One commonly hears about how people, and teenagers in particular, tend to spot hypocrisy in the church. Harmon (2023) identified hypocrisy as a driving factor behind deconversion in her selection of atheists. But one study asked the question: how prominent a factor is Christian hypocrisy in teenage deconversion (Zarzycka et al., 2023)?

Unsurprisingly, fairly prominent. However this study dug a little further and asked how teenagers identified hypocrisy. Meaning, what made them think that a person was being hypocritical? The answer happens to be related to “identity style,” meaning the teenager’s idea of how identities are formed and maintained. In a world where identity is becoming an increasingly complex issue, it is not surprising that deconversions are increasing in this demographic. But it also related to how irrational the teen felt the person’s beliefs were. Again, irrationality is mediated by the beliefs of the observer, so this isn’t a particularly reliable metric.

How do Teens View Religion in Irreligious Societies?

The final study I wish to discuss was taken within a highly secular European country, and asked the question, how did religion relate to the lives of these teens? Since this was a largely irreligious culture, the perception these teenagers had of religion may be a good metric to predict how teenagers in America will soon view religion.

The answer was very simple. Youths were fine with a person who was religious as a personal matter, but kept their religion out of the culture. And understanding religion helped shed some light on history, but was irrelevant to modern times. Researchers concluded from this that there was a need for religious dialog within social spaces rather than mere religious tolerance.

Summary

To sum up the findings of these studies, youths who have a close relationship with religious family, do not perceive hypocrisy in their religious environment, and have an amicable relationship with peers (meaning they don’t feel forced to compare and they don’t have difficulty fitting in), they are unlikely to deconvert.

If the youth enters adolescents with feelings of doubt, and struggles with self-consciousness across their formative years; if the youth perceives hypocrisy in the church, these are all factors which contribute to deconversion.

After deconversion (which, remember, happens more when the youth’s relationship with family isn’t very close), the teenager is liable to lose what little connection he or she had to family.

As the world becomes progressively less religious, religion is seen as more of a dinosaur – a child to be neither seen nor heard in polite society – and something of a historical oddity.

References

Hardy, S. A., Hendricks, J., Nelson, J. M., & Schwadel, P. (2022). Declines in religiousness dimensions across adolescence as predictors of religious deidentification in young adulthood. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 33(1), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12786

Harmon, J. (2023) Atheists Finding God, Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, MD

Hendricks, J. J., Hardy, S. A., Taylor, E. M., & Dollahite, D. C. (2023). Does leaving faith mean leaving family? longitudinal associations between religious identification and parent‐child relationships across adolescence and emerging adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12876

Puchalska-Wasyl, M. M., Łysiak, M., & Zarzycka, B. (2022a). Deconversion and identity formation in adolescents: The role of internal dialogs and religiousness of parents. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 32(4), 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2021.2003112

Zarzycka, B., Razmus, W., & Krok, D. (2023). Social Anxiety, social comparison, self-consciousness, and deconversion in adolescents: A path analysis approach. Journal of Beliefs & Values, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13617672.2022.2160616

Zarzycka, B., Tomaka, K., Krok, D., Grupa, M., Zając, Z., Hernandez, C., & Paloutzian, R. F. (2023). Perceived hypocrisy and deconversion in adolescents. the mediating role of irrational beliefs and identity styles. Journal of Beliefs & Values, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13617672.2023.2201034

García-Segura, S., Martínez-Carmona, M.-J., & Gil-Pino, C. (2022). Analysis of the perceptions shared by young people about the relevance and versatility of religion in culturally diverse contexts. Education Sciences, 12(10), 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100667