How Human Attitudes Form Versus How We Think They Form

I am a researcher whose primary concern is Conversion (meaning how people transition into a religion) and Deconversion (meaning how people transition away from religious practice and belief). As such, it is within my interest to study how humans form attitudes, come to conclusions, and change their minds. Since at least the time when Aristotle began to write his philosophical works, it has more or less been assumed that humans form attitudes based on persuasion – meaning that they take in all of the relevant facts to which they have access, and form opinions based on those facts (Gladd & Minervini, 2020). From the early philosophers onward, it was the default assumption that if a person came to a wrong decision, or held to an improper attitude, it was likely that the person had not considered all of the facts related to the issue. This is the origin and underlying principle of most persuasive writing, speaking, and formal debate (Gladd & Minervini, 2020).

It is not just egghead academics who assume that persuasion is the way in which to shape a person’s ideas and beliefs. Most people who change their minds, including on the topic of religion, believe they have done so by way of assessing the pertinent facts and shaping their beliefs accordingly. However, by the 1950s, psychologists were beginning to recognize another phenomenon: when a person recognized that his or her opinion was shared by other people, it reinforced the sense of “rightness” the person had for that opinion (Petty, 2012). This was not altogether surprising, given that the ancient Greeks had also recognized that demonstrating that “everyone else is doing it” was a powerful tool of persuasion (Gladd & Minervini, 2020). However, simply recognizing that others believe a thing is not a logical way of demonstrating the truthfulness of that thing (known as the “bandwagon fallacy”) so why did it have so much persuasive power? It was not due to the reasonableness of the argument, but rather some “feeling of rightness” it evoked (Petty, 2012). This raises the question: what is the origin of this feeling?

Another psychological phenomenon which contributed to the shakeup in the psychological paradigm regarding belief-formation was the recognition that humans are “cognitive misers.” Theorists began to suspect that human beings would take mental shortcuts (heuristics) to arrive at conclusions (Petty, 2012). In doing so, the person was minimizing the mental resources and processing time it took to reach conclusions. By using these “rules of thumb,” the person could rapidly sort information without devoting a significant amount of brainpower to the decision. One convenient “rule of thumb” might possibly be that if everyone else holds a certain attitude, the attitude is the right one to hold – explaining the “rightness” felt by people in that position.

These pieces were drawn together and a new theory emerged. It was given the name the “heuristic-systematic model” (HSM) of attitude formation by researcher Rochelle Chaiken in the 1980s (Chaiken et al., 1987). Chaiken approached the problem from the standpoint of persuasion, noting that presentation of facts followed by an intellectual process was not always effective in persuasion and attitude transformation. Chaiken proposed that, in order to preserve mental resources, individuals would frequently sort new information by use of heuristics, described as “rules of thumb” which aided in rapid information sorting. Common heuristics might include “if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is,” or “if the person communicating the information seems very confident it is probably true.” Chaiken concluded that heuristics composed a mechanism by which persuasion occurs and attitudes are formed. After publishing her original research, Chaiken made several extensions and revisions on the model, explaining the triggering mechanisms which might cause a person to engage in systematic processing, and what might trigger heuristic processing instead, as well as underlying motivations (Chaiken & Ledgerwood, 2012).

Measurements of Attitude and Change According to this Theory

The key when it comes to deconversion is confidence. As discussed elsewhere in my writings, religious systems frequently demand high levels of confidence from their adherents. If a religious person suffers lagging confidence, this lack of confidence becomes evidence against the truth of their religion, because if it was true, they would be confident in its truth, right? This need for high confidence – or certainty – has been weaponized against Christians in a method of persuasion dubbed “Street Epistemology,” which I have discussed elsewhere in my writing.

Unsurprisingly, then, confidence is key in the HSM. The HSM proposes two methods by which data may be processed. The systematic model requires more time, effort, and mental resources. However, it has the payoff of instilling more confidence in one’s conclusions. The heuristic method is rapid, and takes very little mental effort. However, it also results in lower confidence in the conclusion (Chaiken & Ledgerwood, 2012). These two modes of information processing are not exclusionary, but may interact with and reinforce one another.

When it comes to attitude formation the HSM suggests that heuristic processing is the default method of sorting information, and that one only resorts to the more effortful systematic processing if one is highly motivated to do so. One might suspect that, as with emotion versus rational thinking, the heuristic is more prone to bias, whereas the systematic is more objective. However, neither of these modes are exclusively biased or objective, and either can have elements of bias or objectivity (Chaiken et al., 1987).

The HSM asserts that there are two principles which seek balance when a person is forming attitudes. The first of these is the least effort principle, which proposes that humans seek to form attitudes as efficiently as possible, and may refer back to already-established attitudes or impressions in the attempt to do so. This would include heuristic rules such as “my side is always right.” The second is the sufficiency principle, under which the individual is motivated to maximize confidence in one’s attitude (Chaiken & Ledgerwood, 2012). These two principles seek a sort of homeostasis within attitude formation, wherein the person may encounter a minimal of discomfort with the attitudes they hold in the environment in which they exist.

So, for example, if one exists within a purely Christian environment with little or no exposure to outside ideas or pushback to one’s own ideas, one is less likely to frequently access systematic processing, given that the truth-value of one’s attitudes are less likely to be confronted, and one does not require a rigorous foundation for those beliefs in order to meet the sufficiency principle in that environment. In such an environment, heuristics would be rewarded because they meet the conditions of the least effort principle. However, if this same person were to enter an environment in which those beliefs are not held by the surrounding community, one would need to then engage in systematic thinking in order to meet the sufficiency principle.

This is referred to in the HSM as the sufficiency threshold (Chaiken & Ledgerwood, 2012). This threshold is defined within the HSM as the level of confidence one desires in order to be comfortable with the attitude one holds. This threshold may move, depending on the environment, as illustrated above. When actual confidence falls below the sufficiency threshold, the person may engage in heuristic processing if the gap between actual confidence and the sufficiency threshold is small. But, when the gap in desired confidence and actual confidence is high, the person is likely to engage in the more effortful systematic processing in order to reach the threshold again. This may result in attitude change if the systematic processing is unable to close the gap, as the person will seek an alternative attitude which will provide the desired level of confidence.

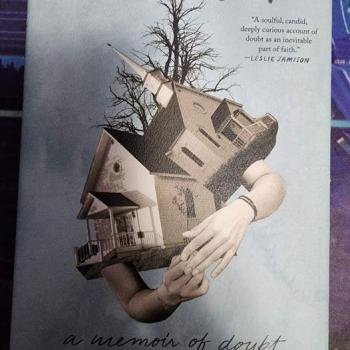

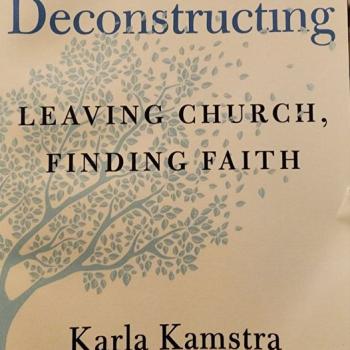

Deconversion frequently occurs when the gap between desired confidence and actual confidence is widened, as with moving to a social environment when one’s peers do not reinforce one’s beliefs, or when encountering material that challenges those beliefs, or when one’s existing heuristics fail to reach the conclusion one has always held to. At this point, the person has to dig into the systematic process of reaching a conclusion, and it can be mentally exhausting. This mental fatigue may in part explain some of the deconversion crisis which follows a person’s exit from his or her religious belief.

Future Use of this Theory

The HSM model was originally developed under the rubric of truth-seeking, taking it as a given that the goal driving attitude-formation was the desire to be factually accurate in one’s beliefs and attitudes. Since then, however, it has become recognized that truth-seeking is not the exclusive motivation within attitude formation (Chaiken & Ledgerwood, 2012). Other motives for attitude formation may include defense motivation and impression motivation. “Defense motivation” refers to personal investment in an idea. Under defense motivation, one is highly invested in one’s attitude or belief, and the cost of losing that attitude or belief is extremely high at the personal investment level. “Impression motivation” refers to the social costs of attitude change, including one’s social status, affiliation, and dignity (Petty, 2012).

For instance, a pastor losing his faith-beliefs is costly at the defense level due to his high existential commitment to those beliefs, his identity-formation within those beliefs, and the personal income which resulted from those beliefs. However, the loss of his faith beliefs would be costly at the impression level due to his social status as a pastor, and his high investment in the faith community.

Beyond her initial publication on HSM (Chaiken et al., 1987), Chaiken has since expanded it into areas beyond mere truth seeking, and now has models which include defense and impression (Chaiken & Ledgerwood, 2012). Another alternative to truth-seeking behavior has recently arisen, and this takes the form of harm-reduction (Vanderslice, 2022). The underlying assumption of the harm-reduction model of attitude formation, is that one is motivated to form attitudes which cause the least amount of harm to self and others. For instance, it is harmful to society to hold racist attitudes, and so one must examine one’s thoughts and beliefs in order to remove any contents which may directly or indirectly cause harm to racial minorities (whether or not those beliefs have caused actual harm or have any truth value). Additionally, one must examine one’s attitudes to minimize self-harm in the form of beliefs or ideas which are perceived to be injurious to personal mental health; whether or not such attitudes have any truth-value (Vanderslice, 2022). While it is possible Chaiken’s work on defense and impression motivations may be mapped on to reduction-of-harm motivations, further work in the field would be required to confirm this.

HSM and Christian Beliefs

HSM relies on heuristics – pre-established rules or ways of thinking – in order to sort new data. This can look a lot like – and in fact include – confirmation bias and disconfirmation bias. A person’s socialization will go a long way toward forming his or her heuristics. So when a person is raised in a church environment, the means by which that person has learned to quickly sort data includes a lot of Christian ideas and principles.

When these heuristics fail to engage new ideas, which may include Biblical contradictions, Christian hypocrisy, life crises, or simply engaging with people who do not share Christian values, the person may begin to grope for new heuristics to explain the world around him or her.

Further, a Christian may tend to have problems with his or her sufficiency threshold. Not only to many church environments demand high confidence or certainty in one’s beliefs, but the person has frequently committed most of his or her life and identity into the religious belief. If so much of who one is depends on one’s beliefs being certain, the gap between desired confidence and actual confidence widens quite easily.

Most of the existing research on deconversion fits comfortably within the Heuristic-Systemic Model of belief formation, and it deserves more attention from deconversion researchers.

References

Chaiken, S. (1987). The heuristic model of persuasion. In M. P. Zanna, J. M. Olson, & C. P. Herman (Eds.), Social Influence: The Ontario Symposium (Vol. 5, pp. 3–39). essay, Erlbaum.

Chaiken, S., & Ledgerwood, A. (2012). A Theory of Heuristic and Systematic Information Processing. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology (pp. 246–266). essay, SAGE.

Dillard, J. P., & Pfau, M. (2002). The Persuasion Handbook Developments in theory and Practice. Sage.

Gladd, J., & Minervini, A. (2020). Writing to Persuade. In Write What Matters (pp. 60–61). essay, Idaho Pressbooks Consortium. Retrieved from https://idaho.pressbooks.pub/.

The Holy Bible ESV. (2007). . Good News Publishers ; Crossway Bibles.

Petty, R. E. (2012). Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to Attitude Change. Springer.

Vanderslice, L. (2022). Heterodox economics and the economics of harm. Journal of Economic Issues, 56(2), 661–666. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2022.2066914