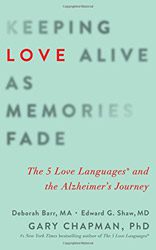

When Gary Chapman first published The 5 Love Languages in 1992, he introduced a tool that could radically change the dynamics of a relationship. As we understand the language of love that different people “speak,” we can hear them in new ways and translate our own care and concern into the language of the other. Chapman’s work in this area undergirds this new book, Keeping Love Alive as Memories Fade. He and co-authors Deborah Barr and Edward Shaw explore the ways these five love languages can support both the caregiver and the one who goes through the darkness of Alzheimer’s.

Patheos reached out to the authors with some questions we thought our readers might wish to ask. Deborah Barr answers here, inviting us into the wonder of love’s power in the darkest experiences.

The 5 Love Languages has been very influential in helping people understand what “speaks” love the best to different individuals. In what ways do these five languages change when loving someone with Alzheimer’s?

As Alzheimer’s disease (AD) progresses, a person’s perception of being loved can change as the brain itself changes. One care partner, Betsy, noticed these changes in her husband. She told our focus group, “As care partners, we have to determine what their love language is at every point. It changes.”

As Betsy noted, AD can cause the love languages to become a “moving target.” This can be illustrated using ballroom dancing as a metaphor. Think of the couple as dancing, with the person with the disease taking the lead and the healthy partner adapting their steps as the music—the disease—requires them to change the routine, or for our purposes, adapt to the change in love language. It is always the care partner, not the person with the disease, who must adapt, modifying the metaphorical “dance steps” of the love relationship.

Take for example, the love language of Gifts. The gifts a person with Alzheimer’s wants, or what constitutes a gift to them, can change as their function changes. Items he or she would have once been delighted to receive as gifts may no longer be meaningful, or even recognized. When this happens, a more meaningful gift may now be an edible treat such as a piece of chocolate. Prior to her Alzheimer’s disease, for Ed’s wife, Rebecca, Gifts was the least meaningful of all the love languages; dead last if she were to rank their importance to her. As her disease progressed, Rebecca’s greatest delight became receiving the gift of an ice cream cone from Ed after dinner each evening.

Another example of a changed love language can be seen in a couple we mention in our book. When Malik and Aisha got married, Physical Touch was Malik’s primary love language, but it was not very meaningful to Aisha, whose love language was Acts of Service. After Aisha got Alzheimer’s disease, as is often the case, they began to disconnect from one another and Malik grew less interested in their physical relationship. As Aisha’s disease progressed, ironically, she and Malik literally switched places in terms of their need for physical touch. Aisha became distraught about the absence of physical affection in her marriage. She now needed to experience Malik’s love in a way that had not been important to her in the past. In counseling, Dr. Shaw helped Malik and Aisha use Physical Touch and Quality Time to reconnect with one another.

Is there one love language that best endures the ravages of dementia, or do they each continue in their own ways?

Early in the disease, a person’s natural primary love language is still likely to be the most meaningful to them, so we suggest majoring on that love language. Later on, even when a person can no longer initiate or reciprocate love in any way, we believe they are still capable of receiving love. So we think the love languages are best used a bit differently late in the disease. In the book, we share a story to illustrate why we think so:

Ed’s daughter, Carrie, had spent the day with her mom, Rebecca, who was declining with Alzheimer’s disease. When Carrie tucked her mom into bed that evening, Rebecca looked up at her and said, “It was so much fun playing with the big kids today!” At this stage in her disease, Rebecca was clearly perceiving life from the point of view of a child.

In their book, The 5 Love Languages of Children, Gary and his coauthor, Ross Campbell, suggest that while parents should try to identify their child’s primary love language, they should deliberately speak all five love languages with their child. Taking our cue from this book, when Alzheimer’s causes people to regress to a childlike state of mind, we recommend expressing love to them as if they were, in fact, children—by using all five love languages. We also think this is a prudent approach because a person’s love language can change throughout the disease. When no particular love language stands out as primary, expressing love in five different ways only increases the chances of get the “you are loved” message across.

How do caregivers receive love when their beloved is no longer able to remember or communicate?

When one’s husband or wife can no longer reciprocate or initiate gestures of love, the healthy spouse often suffers from what Gary calls an “empty emotional tank.” We’ve devoted a chapter to the solution we recommend: for friends and family members to step in and reach out to the care partner with generous doses of love in that care partner’s own primary love language.

There are quizzes in the book that care partners can take to discover their primary love language. When the care partner’s love language is known, and shared with friends and family, they are equipped to reach out in meaningful ways to support and encourage stressed out, discouraged, or lonely family caregivers. In the book we give suggestions for creative ways to do this in each of the five love languages. We also remind readers that anything they do to help the care partner ultimately benefits the person for whom they care as well.

Your book talks about hesed, the abiding compassion that comes alongside. What enables caregivers to operate out of this hesed instead of out of frustration and fear?

Throughout the book, the word hesed is a recurring theme. We have used this word to describe the “gold standard” of dementia care—the loyal, merciful, intentional love that intervenes on behalf of loved ones and comes to their rescue. In antiquity, this Hebrew word was used to describe the love of God Himself for humanity. There has never been a higher love than the hesed of God, and many care partners tell us it is their deep personal relationship with this loving God that empowers them to love the person in their care so well, even in the midst of all the frustrations, fears, and difficulties that are inherent to the caregiving experience.

How can love actually grow and thrive for another even when it’s a one-way street?

The best answer we can offer is to share Gracie’s story. Gracie’s husband, Ken, has frontotemporal dementia (FTD), a less common type of dementia that causes him to be rude, emotionally indifferent to Gracie, and apt to behave in socially inappropriate ways that are embarrassing to his family. Since the day 12 years ago when Ken told Gracie, “I will never touch you again,” he has remained physically and emotionally isolated from her.

When we interviewed her for the book, Gracie was depressed, emotionally wounded, and in a way, hated Ken for his awful treatment of her for so many years. We challenged Gracie to an experiment: shower Ken with love using the five love languages and see what might happen. Gracie was reluctant, so we reminded her that she had nothing to lose.

With an admittedly less than great attitude, Gracie accepted our challenge. We gave her lots of support: Ed provided one-on-one counseling; Gary provided one-on-one guidance in living out the love languages, and Debbie provided supportive friendship, meeting her for coffee and connecting by phone. Gracie poured on the love and, sure enough, not long into the experiment, something changed—but not with Ken.

Gracie realized that her love for Ken was conditional, while God’s love for her is unconditional. This realization changed her whole outlook. She told us, “I began to get so excited about showing Ken unconditional love. I began to do these kindnesses for my pleasure and to honor God. I started to have fun with it.”

Gracie’s outpouring of one-way love did not change her husband, but it did change her in positive ways that persist to this day.

In the last chapter of the book, Debbie reflected, “Gracie’s story showed me that when love is truly given from the heart, even when that love is spurned or goes unreciprocated, the giver can still find fulfillment and sometimes even joy.”

In what ways is journeying with a family member through dementia a form of grieving a death-before-death?

Grieving a loved one’s death before it happens is known as “anticipatory grief.” One spouse caregiver, Rick, described it to us like this: “You know that it’s not going to end well, and every so often that just hits you. You have good times and you have really bad times, but always on your shoulder is this idea that there is a great sadness ahead of you and there’s no getting around it.”

On average, people live 8-10 years after a diagnosis of AD. The grief of those walking alongside the diagnosed person changes with the course of the disease. Typically, loved ones’ grief surges at the time of diagnosis, then levels off in the middle of the disease, resurging again as the journey’s end approaches.

In the beginning, usually both the family and the person with dementia grieve the diagnosis. In the early and middle stages of the disease, they grieve different things. Loved ones grieve the diagnosed person’s declining cognition, changing personality, and behaviors while the person with the disease grieves their loss of abilities and independence. In late AD, when the person with the disease has lost insight about what is happening to them, family members grieve the journey’s end alone.

There are many states considering end-of-life amendments granting the “right to die” with physician’s help. Can you speak to the value of life and relationship even through the suffering of dementia?

Perhaps the best way to respond to this question is to allow family members walking the Alzheimer’s journey with their loved ones to speak for themselves. These excerpts from our interviews clearly show the value they place on the life of their loved one and their relationship with that person, despite their dementia.

Here is a “vox pop”:

Troy, husband of Danielle, now in the late stage of AD: “I just take in those moments when I can love on her. I’m going to love her as long as I’ve got her.”

Rick, husband of Stephanie, and her primary care partner for the past five years: “I really feel our love has grown stronger because of this illness. She’s become like a child to me, a child that I love, and someone I would do anything for.”

Angela, wife of Henry, who has early-onset AD: “I can still see the love in my husband’s eyes and the love in his smile… That smile will mean the world to me, so I want to really hold onto the memory of that as he progresses. We just hold on to whatever little thing it is that helps us to still have a part of them and who they were to us or are to us.”

Penny, wife of Dennis, and his primary care partner for the past seven years: “I realized, not too long ago, that I was so glad that this was happening to Dennis instead of me, because I don’t think he could bear this heartache… I knew then that I loved him more than I had ever known. I think we grow into (caregiving). I think it is the best part of ourselves. It really is the most important thing we’ll ever do.”

Coauthor Ed Shaw’s reflections on his relationship with his wife Rebecca, whose AD inspired our book: “If I could somehow carry this burden for her, trade her diseased brain for my normal one, I’d do it without a second thought… If I had known before we married that she was going to develop early-onset Alzheimer’s, I still would have married her in a heartbeat. The life we’ve had—now 40 years together, 36 of them married, three children, a son-in-law, and two grandsons—has been more than we could have ever dreamed. And I have learned, through the grace of God, to find an endless supply of love for Rebecca and to maintain emotional intimacy with her.”