If I had to name a role model in my life, it would have to be my Grandma Martha. Not only was she born and raised on the Minnesota family farm, homesteaded in the mid 1850’s by her Norwegian immigrant forebears, but — loving the farm life and marrying a farmer — she remained there, devoting herself primarily to the growing, preserving, and cooking of food for the rest of her 92 years. But like most women of her time and location, she was also adept at other skills required for self-sufficiency. She could sew, drive a team of workhorses, and help deliver calves, piglets and lambs. She could nurse a sick child without the benefit of antibiotics. She could wash and lay out the dead. Yet along with all this arduous physical labor, she was a voracious, intelligent reader with a wide-ranging grasp of a world she’d never see. When I was a child, I thought she was the strongest, most fascinating person I’d ever met. And as her eldest grandchild, I and she were especially connected.

Yet the last time I saw her, she was lying on her side, vacant-eyed, in a memory care facility miles from the farm. It took her awhile to figure out who I was, and then I’m not positive she wasn’t pretending. The decision to admit her had been an excruciating one for my aunt, but there was nothing left to do: during the preceding year and a half, Grandma Martha had become increasingly confused about what year it was and which of the countless friends and relatives who had passed through her life during the previous nine decades were now standing in front of her, asking for recognition. Several times, she’d wandered away from the farmhouse in her flannel nightgown, struggling through snowdrifts on her way to “school.” Twice, she’d nearly frozen to death.

Losing loved ones invariably shakes up our lives. But losing them to Alzheimer’s — losing them for months and even years before they actually die — is a particularly wrenching experience. Where do they go, these incredibly dear human beings we’ve known so intimately? Who is holding them captive? And perhaps most importantly, how can we learn to love them in a whole new way?

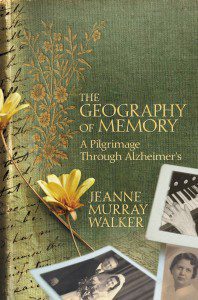

The genius of Jeanne Walker Murray’s wonderful new book, A Geography of Memory, lies in its unflinching confrontation with these painful questions — questions that force us back to square one in regard to our most deeply held beliefs. An accomplished poet, Walker Murray trusts in the transformative power of image and the intuitive intelligence of story, and thus she never succumbs to the usual temptation of Christians writing about suffering, the temptation to offer too-often facile or pious-sounding parallels with the sufferings of Christ. Instead, she approaches this long tale of her mother’s descent into Alzheimer’s with the calm, necessarily detached, but deeply compassionate eye of the artist. And because she is so committed to telling the truth in all its complexity, she is not afraid to laugh when laughter is called for.

For many years, I’ve missed the person my grandma once was. Reading A Geography of Memory has helped me lay my grief to rest in a way that no other book has ever done. I cannot recommend it highly enough.

For more on The Geography of Memory – including a book excerpt – visit the Patheos Book Club here.

Paula Huston is the author of the critically acclaimed novel Daughters of Song, plus six works of creative nonfiction. Her essays and short fiction have been honored by Best American Short Stories, Best Spiritual Writing, and the National Endowment of the Arts. She currently teaches in Seattle Pacific University’s MFA in Creative Writing program.

Paula Huston is the author of the critically acclaimed novel Daughters of Song, plus six works of creative nonfiction. Her essays and short fiction have been honored by Best American Short Stories, Best Spiritual Writing, and the National Endowment of the Arts. She currently teaches in Seattle Pacific University’s MFA in Creative Writing program.

Her latest book is a novel called A Land Without Sin.