Over at Pajamas Media, I have a piece that you might call an addendum to my weekend article at First Things.

In 2009 an Arizona woman, pregnant with her fifth child and suffering from pulmonary hypertension (an often, but not always fatal complication), consulted with her doctor and the ethics committee member on call — a Catholic Sister of Mercy — and obtained an abortion at the St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center.

As the story has gone public, the reactions have been predictable across religious and political lines. […]

Another outfit had asked me to contribute an op-ed on the story. I gathered that they wanted something reflecting the popular “heroic-nun-oppressed-by-menacing-bishop” narrative, or the provocative “menacing-bishop-personifies-everything-wrong-with-church,” model, but I wasn’t feeling either slant, because I understood–as secularists really do not–that there is nothing “obvious” in this story. When things become “obvious” we all stop thinking and move on auto-pilot. For political concerns autopilot may or may not be useful, but precisely because we humans are gifted with reason, these issues that touch the soul can never be cruised through.

Contemplating how confounding secularists find the church (when they and politicians are not grumbling that the Bishops should shut up about abortion or risk being taxed, they’re telling them “I want you to instruct your, whatever the communication is — the people . . .sitting in those pews and you have to tell them that this is a ‘manifestation of our living the gospels.”) it struck me that this whole story was a microcosm of what Catholicism is, and that the worldly world cannot help but be dissatisfied, and always a little confused by it.

If Catholicism is anything, it is the constant struggle to commingle faith to reason, and to seek the boundless depths of a question, because God resides there, in the boundlessness. This struggle is common to all of us–it is a small-c catholic tension–but it exists only to those depths into which we are willing to entertain a question. How earthbound or heavenward we wish to train our focus depends on how far we are willing to step away from ego and comfort-zones and the “certain” knowledge and judgments to which we cling. It all factors into our struggle, our personal, internal Isra-el.

That is why two featured pieces on the abortion story, run concurrently at First Things last weekend, kindled thoughtful debate in the comments threads, yet clearly left many participants unsettled and unsatisfied.

There is always this wish, with humans, to settle everything, to have certainties, and so we are quick to claim them and apply them to everything, including our understanding of God. Our God of Love, after all, cannot possibly want anything for us but our good. And who should know better than us what that good is?

A paradox of faith is that only by giving away the judgments and notions can we attain anything like Godly wisdom. Only by saying, “I surrender my notions of what would make me happy, to wholly accept yours,” can we hope to find true happiness and that peace “which defies all understanding.” Jesus went through an awful lot to demonstrate the power (and value) of “thy will be done,” and yet, we still struggle with it; we still resist, and want our own way.

Anne LaMott likes to quote a priest-friend of hers: “You can safely assume that you’ve created God in your own image when it turns out that God hates all the same people you do.”

Or, taken another way, “you can safely assume that you’ve created God in your own image when it turns out that the plan God has for the world is, by happy coincidence, precisely aligned with your positions.”

The saints, from the Acts of the Apostles and throughout history, tell us differently. So do Mary, and Joseph. And David. And Jacob. And Abraham.

Our thorns in the flesh are not arbitrary miseries; they are personal, individual and valuable challenges. Our crowns are made from them.

In his last homily as Cardinal Ratzinger, Pope Benedict XVI’s “dictatorship of relativism,” grabbed the worldly headlines; missed amid the resulting hoopla was this:

” . . . the Lord calls us friends, he makes us his friends, he gives us his friendship. The Lord gives friendship a dual definition. There are no secrets between friends: Christ tells us all that he hears from the Father; he gives us his full trust and with trust, also knowledge. He reveals his face and his heart to us. He shows us the tenderness he feels for us, his passionate love that goes even as far as the folly of the Cross. He entrusts himself to us, he gives us the power to speak in his name: “this is my body…”, “I forgive you…”. He entrusts his Body, the Church, to us.

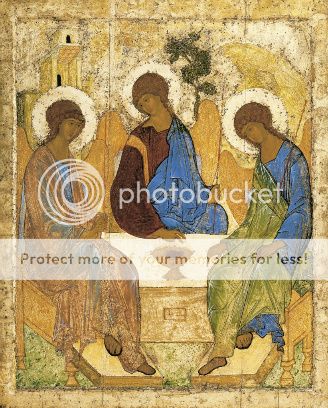

To our weak minds, to our weak hands, he entrusts his truth – the mystery of God the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit; the mystery of God who “so loved the world that he gave his only Son” (Jn 3: 16). He made us his friends – and how do we respond?

Well, usually, because we are both contumacious and beholden to our senses, we respond with a “give me,” and not with a “please take.” And yet, we are told in this very sermon that there are no limits, and Jesus said it himself, in the Gospel of John: “If you remain in me and my words remain in you, ask for whatever you want and it will be done for you.”

Do we believe it? If we do, we’re invited to pursue that promise. There are no limits to what God will teach us and tell us and give us, if only we do not limit his access.

We humans tend to try to put everything, including God, and love and life, into manageable compartments, and we hide in them. We hide inside our frameworks, our structures, our plans, our narratives, our willful and our unintentional bigotries.

But God -who created a world of order- points cannons at those tidy compartments and goes ba-boom! And when we ask, repeatedly, “why did you do that, when I had it all so beautifully arranged,” God says, “it was blocking my love. My love couldn’t fit with all that stuff in the way.”

Yes, moving past our illusion that things are cut-and-dry, and that we have it all figured out, is as I write in this piece at PJM, a most catholic drama.

Related:

Fr. Dwight Longenecker: Holy Spirit, Me and Church