One of the welcome results of the demise of fusionist conservatism and the ensuing post-liberalism discussion, which has yielded or melded with (its hard to tell) the reassessment of originalism as the established conservative jurisprudential outlook, is widespread interest in examining legal texts and opinions of the early republic. A disenchantment with bare (allegedly neutral) proceduralism and positivism, and the search for the common good through jurisprudence (as well as some “conservative” victories for once, which seem to elude the grasp of conservatives themselves no matter how many Republican appointees sit on the bench), has led to some soul searching— an ad fontes movement of sorts; a realignment of commitments on a substantive (and metaphysical) if less tidy basis over and against the orthodoxy of the Lockean classical liberalism and the libertarianism of the Federalist Society that has dominated the conservative legal landscape for decades.

The lion’s share of this emerging intramural conversation centers on conceptions of the common good, whether societal cohesion and tranquility is possible absent one, and what that means for politics. In turn, many commentators are asking important questions about the relationship between church and state, and religion and society vis a vis the common good. What moral commitments are necessary (and were previously assumed but now lost) for our republic to flourish? Is there a worldview that serves as prerequisite for the intelligibility of our most cherished values and governing principles? Is pluralism tenable? Was America founded as a Christian nation? Et cetera.

Brief Bio

In examining early American sources, Joseph Story (1779-1845) is as good a place as any to start. His jurisprudence was built on assumptions and commitments regularly scoffed at today, and his political opinions may seem now unworkable– especially in the subject examined below– but his brilliance and prominence (in his own day) deserve our attention— doing so might enable us to see present challenges in a better light, and question our own deeply held (but never as certain as we think) assumptions.

A native of Massachusetts, Story grew up in a staunchly Calvinist family— which is, partially, how we justify featuring him here at TCC. His was also a founding family, so to speak; his father was a member of the Sons of Liberty and joined in the ruckus at the Boston Tea Party (1773). After studying at Marblehead, Story attended Harvard, where he would later teach (from 1829), graduating second in his class before reading law and being admitted to the bar in 1801.

By all accounts, Story was the most brilliant justice to ever occupy the bench. More quantifiably, he remains the youngest to ever serve on the Supreme Court (32 years old), with the added honor of being appointed by the father of the Constitution, James Madison, as the successor to William Cushing. He served on the Court from 1812-1845 (i.e. Marshall and Taney courts).

Story’s political outlook was that of the old republican (and nationalist) guard of the founding era, viz., Alexander Hamilton and John Marshall. His jurisprudence evidences the assumptions of the classical legal tradition, found in Marshall as well as James Wilson, Samuel Chase, and others— human law must conform to natural law, the state has a vested and legitimate interest in regulating public morality and religion, and the government rightfully possesses leeway in the power of determination of human law (see e.g. Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee, 14 U.S. 304 (1816). Story’s jurisprudence also acknowledged the plurality of influences on the judge. What Hadley Arkes (borrowing from the anti-federalist essays of “Brutus”) refers to as the “reasoning spirit” of the Constitution, that is, the general principles upon which the republic was predicated in addition to the text itself— both law and equity— would govern as judges filled in the interstices of the law (as Story himself acknowledged, the text of the Constitution itself was, by design, general and thereby fitted to the character of the common law). The operation of, and dependence on, the “underlying canons of jural reasoning” (Arkes) are evident in Story’s writing. (See also generally R.H. Helmholz’s “The Law of Nature and the Early History of Unenumerated Rights in the United States,” U. Pa. J. Const. L. 401 (2007)). Additionally, as we will see, Story was utterly convinced that Christianity served as the foundation of the Anglo-American common law tradition, that without it, our laws and ways of ascertaining law and achieving justice would become untenable (an opinion that, as I recently pointed out, he shared with many of the founders).

For some famous Story cases (relevant to the subject at hand) see Terrett v. Taylor (1815), Pawlet v. Clark (1815), and Vidal v. Girard’s Executors (1844). Fun fact: Story was portrayed by Justice Harry Blackmun in the film Amistad (1997) which featured the case of United States v. Schooner Amistad (1841), occurring in the last few years of Story’s storied tenure.

Story and Christianity

Story’s theory of church and state corresponds to his understanding of Christianity’s influence on the Anglo-American legal tradition. In this, his view still harbored much of a classical outlook, as did the generation of jurists that preceded him. Story famously endorsed the maxim, “Christianity is a part of the common law,” and, therefore, deeply intertwined with not only the text of the constitution but the norms of the republican government implied therein. In a speech at Harvard, where he taught for many years, he stated this idea even more clearly,

there never has been a period of history, in which the Common Law did not recognize Christianity as lying at its foundation.

Story’s position on Christianity and the Constitution has been compared to that of Chancellor James Kent’s, best represented in New York Supreme Court case People v Ruggles, 8 Johns. R. 290 (N.Y. 1811), one of the few cases in American history to uphold a blasphemy conviction.

Therein, Kent held that, despite the disestablishment of religion in the New York constitution, blasphemy against the name of Jesus Christ (and disparaging his mother, as was the case in Ruggles) was a common law crime (against public tranquility and morality), inherited from English tradition (as were those against other recognized immorality and those honoring the Sabbath). This aspect of English law had, indeed, successfully swam the Atlantic since both peoples were in need of “all the moral discipline, and of those principles of virtue, which help to bind society together.”

Kent in no way saw this ruling as contradicting disestablishment policies, which, in his view, simply outlawed persecution via “tests, disabilities, or discriminations, incident to a religious establishment.”

This did not mean that the Christian religion, at least in its basic, ecumenical form, could not be protected (and favored) by the government. For it served a particular need: that of fostering virtue and social cohesion. The same privilege was not to be afforded to “the religion of Mahomet or the Grand Lama,” because, per Kent, “we are a Christian people, and the morality of the country is deeply ingrafted upon Christianity, and not upon the doctrines or worship of those imposters.”

Even in his own day, Story was an accomplished author. His Commentaries on the Constitution (1829-1833) are the greatest gift given by his pen but almost as neglected today as John Adams’ commentaries on the same subject. It is to them we now look for further insight on church and state vis a vis our Constitution.

Section 986-993 (Bk. III. Ch. XLIV) (examining the first amendment’s establishment and free exercise clauses):

The right and the duty of the interference of government, in matters of religion, have been maintained by many distinguished authors, as well those, who were the warmest advocates of free governments, as those, who were attached to governments of a more arbitrary character. Indeed, the right of a society or government to interfere in matters of religion will hardly be contested by any person who believe that piety, religion, and morality are intimately connected with the wellbeing of the state, and indispensable to the administration of civil justice. The promulgation of the great doctrines of religion; the being, and attributes, and providence of one Almighty God; the responsibility to him for all our actions, founded upon moral freedom and accountability; a future state of rewards and punishments; the cultivation of all the personal, social, and benevolent virtues;– these never can be a matter of indifference in any well ordered community. It is, indeed, difficult to conceive, how any civilized society can well exist without them.

And at all events, it is impossible for those, who believe in the truth of Christianity, as a divine revelation, to doubt, that it is the especial duty of government to foster, and encourage it among all the citizens and subjects. This is a point wholly distinct from that of the right of private judgment in matters of religion, and of the freedom of public worship according to the dictates of one’s own conscience.

Story evidently thinks everything contained in the above quote beyond serious dispute. “The real difficulty,” he says, “lies in ascertain the limits, to which government may rightfully go in fostering and encouraging religion.”

It is no question, for Story, that the government has some duty to “interfere” (not a pejorative here) with religion and public morality. It must encourage religion, and as proven above, Story was clearly of the old opinion that Christianity was true religion and, therefore, the only one worth promoting. Freedom from abuse was extended to other religions but only Christianity would be actively promoted and favored by the government. Toleration pertained primarily to a pluralism of Christian denominations (see below), which was necessary to hold together the diversity of colonies (e.g. Catholic Maryland, Congregationalist Massachusetts, and Episcopalian Virginia). The lingering question simply pertains to the mode, manner, and measure of said interference.

Story gives three model, if theoretical, options for framing the limits of government in religious interference. First, a government can give aid to a particular religion whilst leaving everyone free to adopt whatever faith they please. Second, a government can create an established religion of a particular sect whilst allowing dissenting citizens to coexist outside the established church. And third, the government can establish one church to the exclusion of all others and also exclude (“either wholly, or in part”) all dissenting citizens “from any participation in public honours, trusts, emoluments, privileges, and immunities of the state.”

The first model promotes Christianity generally (ecumenically) through governmental aid, encouraging “all the varieties of sects belonging to it.” Alternatively, the second and third models designate a particular sect or denomination— although here Story still speaks broadly, offering Catholicism and Protestantism as examples when we, as well as he, know that Protestantism has always been fissiparous and itself contains numerous, disagreeing sects (Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anabaptist being the most basic and original during the Reformation)— as the official religion of the state. In the second model, limited toleration for dissenters is still provided. In the third model, no such public/political toleration (which seems to be what Story has in mind) is afforded.

By Story’s lights, the first option or model characterizes the opinion and intent of the founding generation. Christianity (ecumenically) was favored. Toleration for non-Christians was implied. But this did not infer a flattening of all religions into irrelevance.

Probably, at the time of the adoption of the Constitution, and of the Amendment to it, now under consideration, the general, if not the universal, sentiment in America was, that Christianity ought to receive encouragement from the state so far as was not incompatible wit the private rights of conscience and the freedom of religious worship.

An attempt to level all religions, and to make it a matter of state policy to hold all in utter indifference, would have created universal disapprobation, if not universal indignation.

Story clarifies that the state’s duty to support Christianity does not justify, nor, indeed, make possible, the violation of conscience.

But the duty of supporting religion, and especially the Christian religion, is very different form the right to force the consciences of other men, or to punish them for worshipping god in the manner, which, they believe, their accountability to him requires…. The rights of conscience are, indeed, beyond the just reach of any human power. They are given by God, and cannot be encroached upon by human authority, without a criminal disobedience of the precepts of natural, as well as of revealed religion.

That being said, “The real object of the First Amendment was not to countenance much less to advance Mohammedanism, or Judaism, or infidelity, by prostrating Christianity, but to exclude all rivalry among Christian sects [i.e. denominations] and to prevent any national ecclesiastical patronage of the national government.” Rather, its purpose was to “exclude all rivalry among Christian sects, and to prevent any national ecclesiastical establishment, which should give to an hierarchy the exclusive patronage of the national government.” (This latter clause may be a not so veiled expression of anti-Catholic fears and sentiments still prevalent at the time). Through this model, the “means of religious persecution” (e.g. exclusion from political activity) and “the power of subverting the rights of conscience in matters of religion.”

Story clearly did not want heresy, apostacy, or nonconformity to be punished by the government, nor for membership in a particular denomination to serve as prerequisite for national office. Without these allowances, which Story deems objectively good (see Section 992), the union would fracture into as many pieces as there were religious opinions. “The only security was in extirpating the power.”

But this did not prevent the government from, under Story’s preferred model, promoting Christianity generally and in ecumenical fashion. Nor did it necessarily rule out state-based (n.b. this was all pre-incorporation of the bill of rights to the states) established churches. “Thus, the whole power over the subject of religion is left exclusively to the state governments, to be acted upon according to their own sense of justice, and the state constitutions; and the Catholic and the Protestant, the Calvinist and the Arminians, the Jew and the Infidel, may sit down at the common table of the national councils, without any inquisition into their faith, or mode of worship.” (emphasis added).

But even state level establishments were trending downward in Story’s day, as he alludes to (Section 992). By the time his Commentary was completed (1833), his beloved Massachusetts had disestablished the Congregational church, ending its 200 years of dominance (but, in truth, as Harry Stout argues in The New England Soul, the last 100 years of establishment in the old colonies was really a tale of slow decline and dwindling influence). And as I’ve noted recently (channeling Justice Thomas), the Establishment Clause jurisprudence of the last century has been almost totally botched. It is doubtful that the Fourteenth Amendment actually incorporated the Clause into the states, but even if it did, per Thomas the application has been a near unmitigated mess.

Back to Story: He doubts the longevity of governments and societies that do not support religion or the public worship of God.

It yet remains a problem to be solved in human affairs, whether any free government can be permanent, where the public worship of God, and the support of religion, constitute no part of the policy or duty of the state in any assignable shape. The future experience of Christendom, and chiefly of the American states, must settle this problem, as yet new in the history of the world, abundant, as it has been, in experiments in the theory of government.

In this excerpt, Story seems less than confident in the dynamic adopted by the federal constitution, even after his laudatory remarks regarding the religious settlement. It is evident to him that support of religion must be a duty of the state and a commitment of society. But the jury was still out on whether a federalist organization of the matter would work… and, perhaps, it still is.

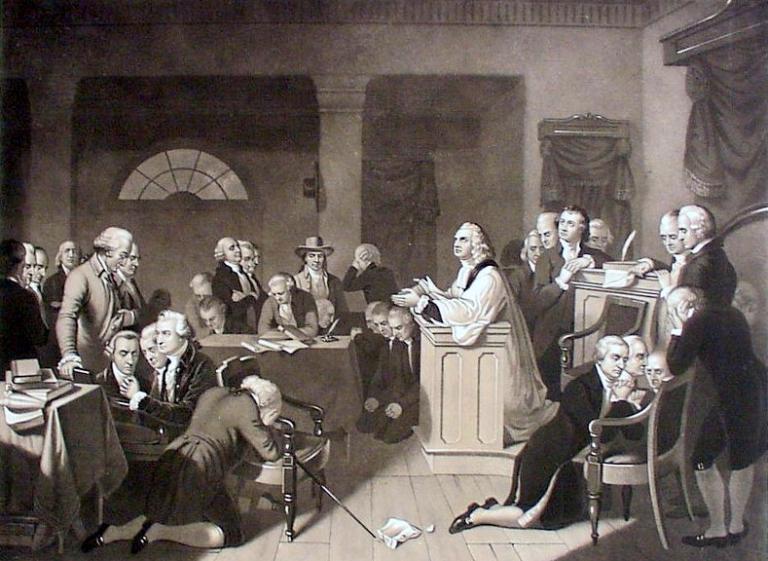

Image: Jacob Duché Offering the First Prayer in Congress, Sept. 7, 1774, by Harrison Tompkins Matteson (1848) (Wikimedia Commons)