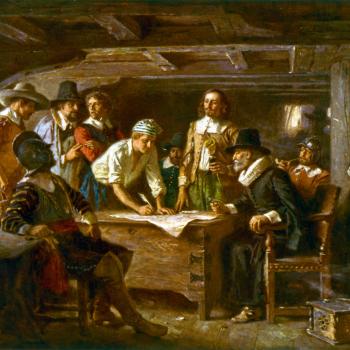

I’m working on a couple of writing projects at the moment. One (the longer one) involves a study of 17th and 18th century New England election sermons and the other one offers a fairly narrow thesis against Theonomy (since all of that is heating up again). In some ways, the two separate inquiries cohere. It is commonplace to hear Theonomists claiming Puritan New England as an exemplar of their theory. There is all kinds of historical reasons this is wrong. And here’s one of them.

Ashbel Woodbridge (1704-1758) preached the annual election sermon in Hartford, Connecticut in 1752. Now, in my opinion, the mid-eighteenth century stands far beyond the Puritan era in the colonies (which probably ceased to exist in any coherent, distinctive way several decades prior thereto). However, despite many theological shifts in the 18th century, Woodbridge’s sermon is highly conventional in relation to the preceding century, and he was still an orthodox, Congregationalist clergyman ministering in an area conditioned by the Puritan heritage and where the legacy of the founding generation still loomed large. Its classic example of a “character of the good ruler” sermon; it reflects the emphases of previous generations in ways that some other election sermons around the same period did not. (Although, my general contention is that the political doctrine expressed in election sermons was remarkably stable for at least a century.) What is interesting for our purposes here is what he says about the judicial law of Moses.

Only a quarter of the way through Woodbridge’s address, he presents the fifth attribute (pp. 11-12) of the good ruler:

“A strict, steady, and conscientious adhering to the Laws of God and the Common Wealth in all the parts of Government, whether we consider it, as subsisting in the Law of Nature, and Dictated by it’s Light; for ’tis Evident from what we find, in our own Breasts, that the Apostle speaks the Truth [Rom. 2:14]; but to assist the Defectiveness and Insufficiency of this Light, it has pleased God to give the civil Ruler, in the sacred Scriptures, in both the Old Testament and in the New, where his Commission, Power and Authority, the Nature and Design of his Office is sufficiently Tau’t as well the General, as many particular Rules, of his Conduct, laid down, which may be seen in part, from such Texts as have been fore-cited [in the previous section Woodbridge cited, and is likely referring to, Deut. 1:16; Ex. 23:3], and many others here & there; and the Body of Judicial Laws, which God gave to the Children of Israel, by Moses, which in their Day were accommodated to the Israelitish Nation, were, by far the most perfect & accomplish’d Body of Laws, to be found Extant in any Nation (besides) whatever; which (doubtless) is a part of the Meaning of that Appeal & Remark [Deut. 4:8; Ps. 147:19-20]: And still, for Substance, are, and will remain the most pure and perfect Foundation, (considered together with what the Sacred Writings do afterward afford, more Accommodate to the State of a Christian People) from whence, every Christian State and Nation, may draw forth such Streams of good & wholsom [sic] Laws, as may (if duly Executed) make Justice & Judgment flow down their Streets as Waters. As the Civil Ruler is accommodated with the most excellent Laws of god; Revealed in the Holy Scriptures: Which, when Fitted and Passed into the Laws of his Realm or State: ‘Tis both Matter of Duty to him, and Interest of his Subjects.” [pp. 11-12].

It would be easy for a Theonomist to read this and think Woodbridge in agreement with them (at least, on the point of the endurance of OT judicial law). They would be wrong. Woodbridge is writing to an audience of which he can assume much, viz., over a century of commentary on these issues on at least an annual basis. And so, he doesn’t quite make explicit everything imbedded in his sermon, or at least not to a level sufficient for those of us separated from him by a sizeable chronological chasm.

The first thing to notice is that Woodbridge says both the light of nature (i.e., natural law) and Scripture cohere in delineating the “Commission, Power and Authority, the Nature and Design” of the magistrate’s office. This is a decidedly general statement. The confines of the magistrate’s purpose and power are outlined in Scripture and evident from the light of nature. Thus far, we’re not in peculiarly Theonomic territory, though the Theonomist would doubtless affirm this (sans too much enthusiasm for natural law). It’s the next bit that might convince Theonomists that Woodbridge agrees with them. I’ll quote Woodbridge again in part:

“… and the Body of Judicial Laws, which God gave to the Children of Israel, by Moses, which in their Day were accommodated to the Israelitish Nation, were, by far the most perfect & accomplish’d Body of Laws, to be found Extant in any Nation…And still, for Substance, are, and will remain the most pure and perfect Foundation, (considered together with what the Sacred Writings do afterward afford, more Accommodate to the State of a Christian People) from whence, every Christian State and Nation, may draw forth such Streams of good & wholsom [sic] Laws…”

Woodbridge is saying several things: 1) the judicial law of Moses is still (in some way) relevant. 2) But what is the judicial law? It is the law of God (i.e., the eternal, moral law) “accommodated to the Israelitish Nation.” 3) These laws were perfect, more perfect, in fact, than can be found in any nation. 4) For their “substance” (that is their immutable, central core drawn from the natural law but apart from the particularity of the law as accommodated to the state of Israel) they remain a “pure and perfect Foundation” (once the insights of the New Testament are factored in which accommodate those laws better to a Christian nation). 5) And from this, a Christian commonwealth can glean good principles of law (i.e., the natural law applied in context) to accommodate to their own context. That is, they can see how the moral or natural law was applied to Israel and learn how to do the same in their own situation.

Woodbridge places this duty upon the magistrate. He is to accommodate “the most excellent Laws of God; Revealed in the Holy Scriptures” to fit them to his particular realm or state. This is prudent and judicious legislative and executive action, and it is no coincidence that on the subsequent page to the block quote above, Woodbridge cover the attribute of wisdom.

In sum, Woodbridge is not, despite what first impressions might assume, saying that the judicial law of Israel is universally and perpetually binding. But he is saying that it advantageous to contemporary Christian magistrates, for from that “Body of Laws” they can learn principles of justice which they can they accommodate to their own commonwealths.

As Woodbridge said a few pages prior, “The Principles of Justice should be deeply Rooted in the Hearts of civil Rulers… [and] must run thro’ all the Laws which they make, as so many Bands and Ligaments to hold the common Wealth together.” And the laws, adhering to the principles of proportionality and equity, must contain a “Suitableness to the common Wealth and their own Design,” which is to say, prudence in human lawmaking. (p. 10).