Nicholas Kristof reflects intelligently on the problems faced by campuses like the University of Missouri and Yale, highlighting the balance between free speech and the embrace of pluralism. Of these problems, he writes:

Nicholas Kristof reflects intelligently on the problems faced by campuses like the University of Missouri and Yale, highlighting the balance between free speech and the embrace of pluralism. Of these problems, he writes:

One is a concern for minority or marginalized students and faculty members, who are often left feeling as outsiders in ways that damage everyone’s education. (…)

But moral voices can also become sanctimonious bullies.

This second observation points to what Nietzsche called ressentiment: a feeling of moral outrage toward those who hold power. For Nietzsche, though, as for any who deny a moral framework in human affairs, there can be no such moral outrage.

(T)he problem with the other origin of the “good,” of the good man, as the person of ressentiment has thought it out for himself, demands some conclusion. It is not surprising that the lambs should bear a grudge against the great birds of prey, but that is no reason for blaming the great birds of prey for taking the little lambs. And when the lambs say among themselves, “These birds of prey are evil, and he who least resembles a bird of prey, who is rather its opposite, a lamb,—should he not be good?” then there is nothing to carp with in this ideal’s establishment, though the birds of prey may regard it a little mockingly, and maybe say to themselves, “We bear no grudge against them, these good lambs, we even love them: nothing is tastier than a tender lamb.”

What we are seeing in the kinds of debates at Mizzou and Yale are a clash of moral frameworks. First: there is a remnant Christian morality, which favors the poor, the outcast, the sinner, as Jesus did. The Civil Rights Movement depended on this framework, as is very clear from the writings of Martin Luther King. Second: there is a lurking libertarianism, driven by laissez faire economic systems which always favor the wealthy and the powerful. Universities have long histories, deep pockets, and institutional and cultural inertia which can tend to favor the powerful. This is the movement that the third framework really wants to attack. It is a liberal ressentiment, rooted in a remnant of Christian morality but divorced from the theological language that gives it its meaning and power. Kristof points to the limitations of this framework:

This is sensitivity but also intolerance, and it is disproportionately an instinct on the left.

Discourse becomes shrill, angry, and even violent; it is no longer tempered with the virtues that the Civil Rights leaders worked so hard to form in their movement.

The problem I see is that these shrill voices can sometimes conflate the first two frameworks, identifying the Christian and libertarian frameworks such that the critique is turned toward God and any moral language attached to Christian belief. There are many reasons for this conflation that I won’t elaborate on here, but I will observe that the fallout of this conflation is that universities have become disproportionately liberal, as Kristof recognizes:

More broadly, academia — especially the social sciences — undermines itself by a tilt to the left. We should cherish all kinds of diversity, including the presence of conservatives to infuriate us liberals and make us uncomfortable. Education is about stretching muscles, and that’s painful in the gym and in the lecture hall.

Consequently, universities are left in a kind of moral vacuum. Kristof points to an irreducible pluralism as the consequence of this state of affairs:

My favorite philosopher, the late Sir Isaiah Berlin, argued that there was a deep human yearning to find the One Great Truth. In fact, he said, that’s a dead end: Our fate is to struggle with a “plurality of values,” with competing truths, with trying to reconcile what may well be irreconcilable.

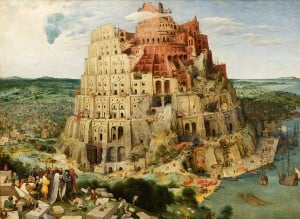

But on this last point, I disagree. A plurality of values–a Babel (“G-d decided to destroy their arrogance by destroying their ability to understand one another.”)–is not our fate. There is another way: a way of civility. The Christian moral framework which gave rise to universities in the first place involves being rooted in intellectual humility, willingness to listen to the other, and willing to embrace a heuristic of the shared search for truth.

In a word, catholicity as an alternative to pluralism. For catholicity is seeking to see things “according to the whole” (kata holos in Greek), rather than as isolated individuals. In this sense, the university is the place where we practice this way of seeing, working hard to invite those who have been marginalized.