Travel is such a pain for multiple reasons. Of course one of these is that I sometimes cannot get to posting anything on here for a whole week, what with travel times, adjusting new schedules, restocking on groceries after being out of town for two weeks, etc. But I digress.

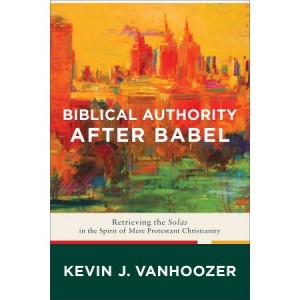

I have been very slowly—due to the aforementioned holiday season travels, as well as reading through about four other books—working my way through Kevin Vanhoozer’s latest book, Biblical Authority After Babel. I am about halfway through it and so far it has been very, very good. Vanhoozer’s larger project in the book is to retrieve the five, historically-rooted, Reformation solas (sola scriptura, sola fide, sola gratia, solus Christus, soli Deo Gloria) as a pattern of theological authority for what he terms “mere Protestantism.” Vanhoozer has heard the critiques of a subjective and naive biblicism among many American evangelicals from Catholic thinkers like Christian Smith in his The Bible Made Impossible and he agrees that this is a problem (Vanhoozer even wrote a blurb for Smith’s book). What Vanhoozer disagrees with is the need to turn to either a magisterium (as in the Roman Catholic Church) or to an aimless, relativistic hyper-subjectivism when it comes to the principal of theological authority for Christians.

Rather, Vanhoozer believes that supreme authority rests in the economy of grace of the Triune God. Sola gratia (grace alone) grounds us first and foremost in the fact that God’s self-revelation and redemption in Christ is an incongruous gift. As Vanhoozer notes, “Sola gratia is a permanent reminder that at the heart of Christianity is good news—the story of what the Triune God is doing in Jesus Christ” (p. 64). This is followed by sola fide (faith alone), the epistemic and volitional means by which such a gift and grounding of all theological authority is appropriated by Christians.

Contrary to many caricatures of the Reformers (particularly Luther), sola fide was not intended to fuel a sort-of “blank check mentality” toward religious authority in conjunction with sola scriptura. Rather, it was always meant to be rooted in both the authoritative apostolic testimony of the eyewitnesses to the risen Jesus, and in the larger interpretive context of the whole church:

“Faith alone” means that individual interpreters had best attend to the authoritative apostolic community (the primary fiduciary framework) as read in the context of the church (a secondary fiduciary framework). The church is not like other interpretive communities. Its reading must not be a function of this or that interpretive interest; the church must not “use” the text for its own purposes. For the church is a “creature of the Word”—an interpretive community that exists not to have its way with the text but to let the Word have its way with the interpreters. John Webster rightly states, “The reading of Holy Scripture is thus a field of divine activity; it is not simply human handling of a textual object. And that divine activity is God’s speech to which we are, quite simply, to attend.” (p. 102; Vanhoozer’s quote of John Webster is from Word and Church: Essays in Christian Dogmatics [Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2001], p. 93)

Vanhoozer thus puts forward that the supreme authority principle in Christian theology and life is the Triune God and His triune economy of grace, which naturally includes Scripture as the chief, post-resurrection and post-apostolic means of His revelatory speak-acting:

The authority principle of mere Protestant Christianity is the say-so of the Triune God, a speak-acting that authorizes the created order and authors the Scriptures, diverse testimonies that make known the created order as it has come to be and to be restored in, through, and for Jesus Christ (p. 104)

Indeed, Vanhoozer affirms that, properly construed, both sola gratia and sola fide are to be understood chiefly within the context of the church as interpretive community and with a critical-realist epistemological framework that navigates between the Scylla of absolute objectivity and the Charybdis of subjective relativism:

Mere Protestant Christians believe that faith enables a way of interpreting Scripture that refuses both absolute certainty (idols of the tower) and relativistic skepticism (idols of the maze). . . . sola fide is the answer to skepticism, for faith yields knowledge but is not a “work.” Faith is, rather, perseveringly confident, patiently attentive, and properly basic¹— a warranted epistemic trust in biblical testimony. . . . True faith has to do not with an anti-intellectual fideism or private judgment, then, but rather with testimonial rationality and public trust, the trust of God’s people in the testimony of God’s Spirit to the reliability of God’s Word (pp. 105-07).

¹Vanhoozer footnotes here: “[Alvin] Plantinga’s term for a belief that does not need to be justified or inferred from any other belief in order to be deemed rational ([Plantinga], Warranted Christian Belief, 175-79).”

Like I said, the book is proving to be excellent so far, and I hope to interact with it a bit more in the future. Time-permitting I may even try and write a review of it.